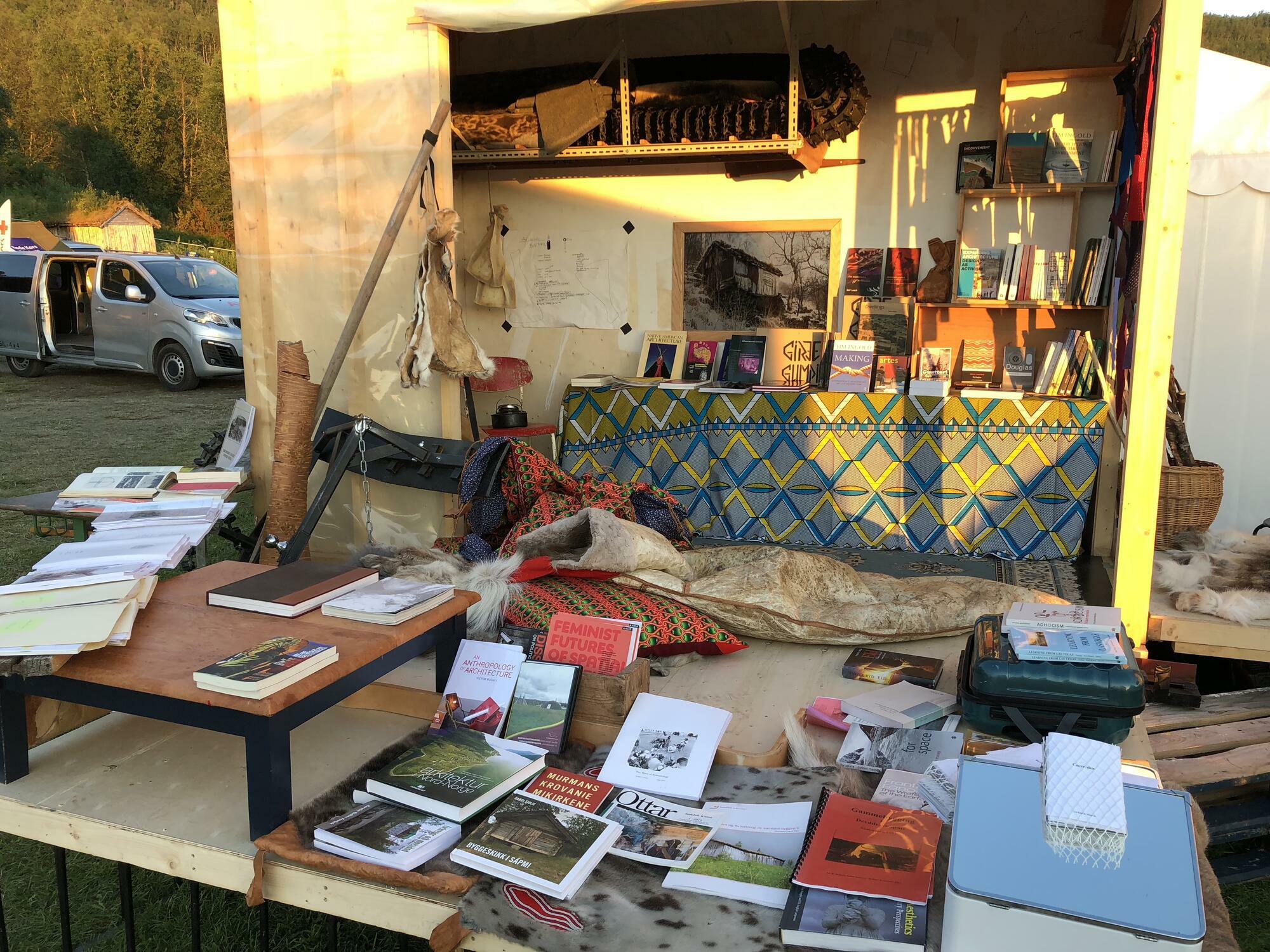

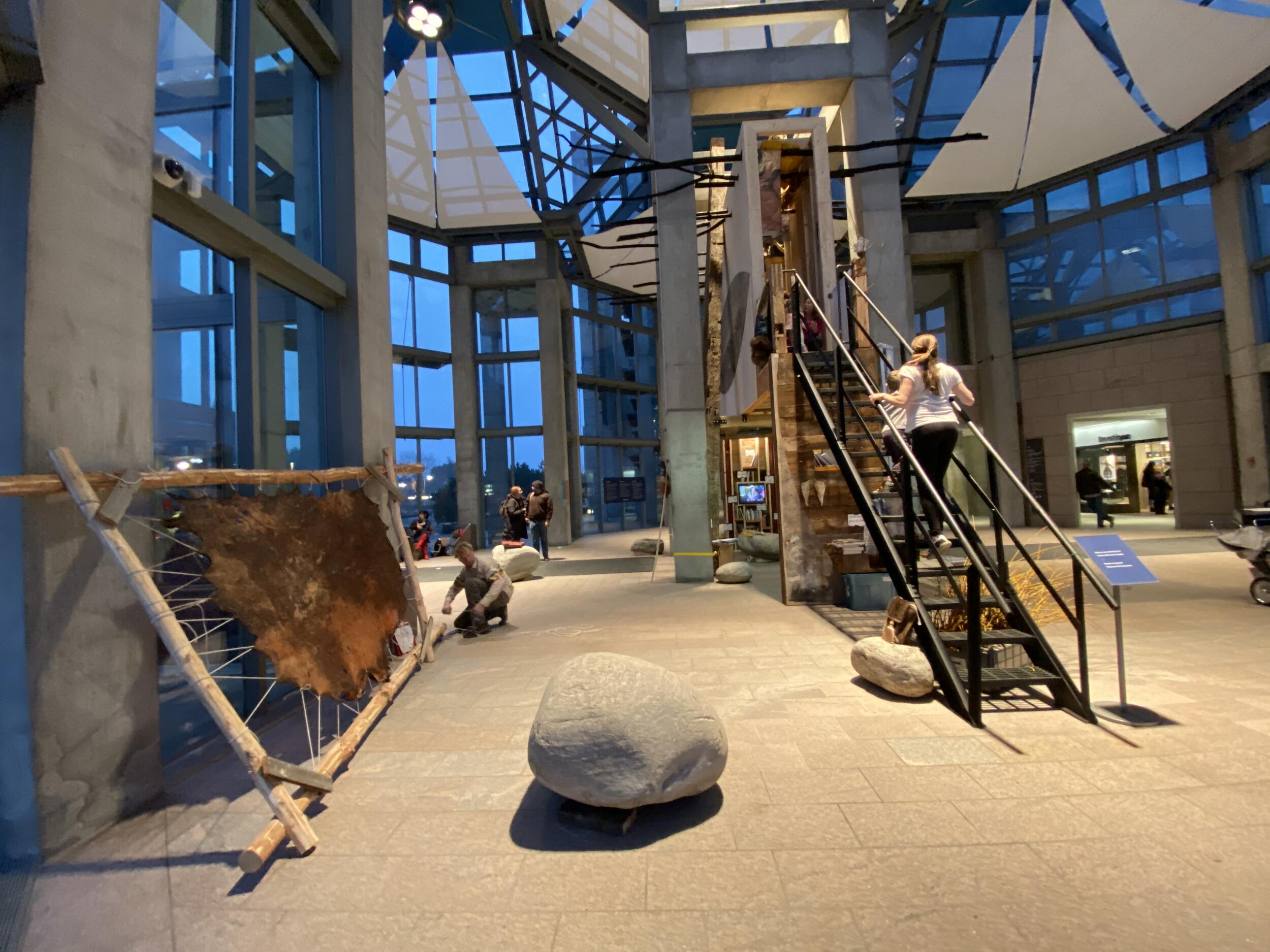

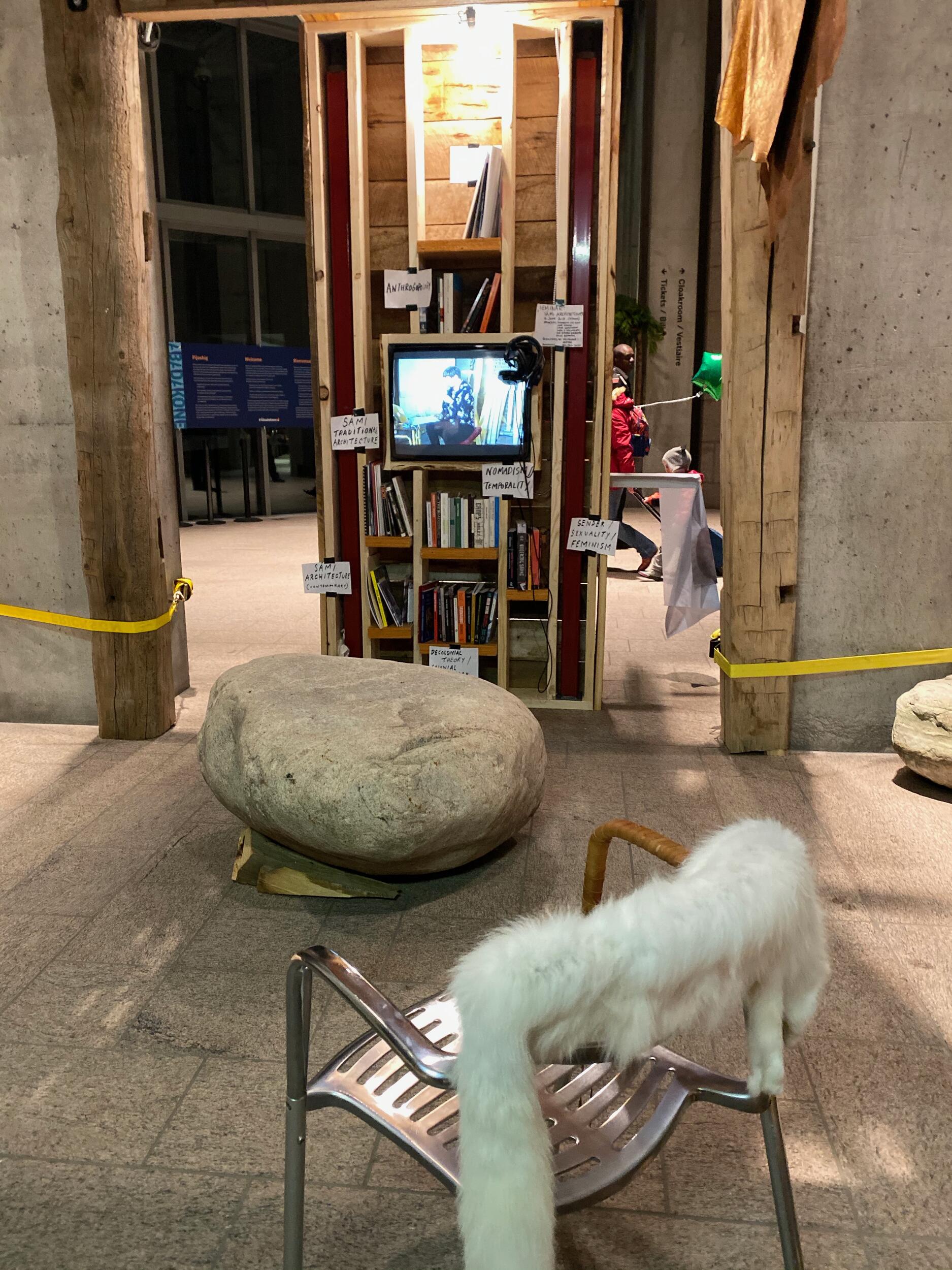

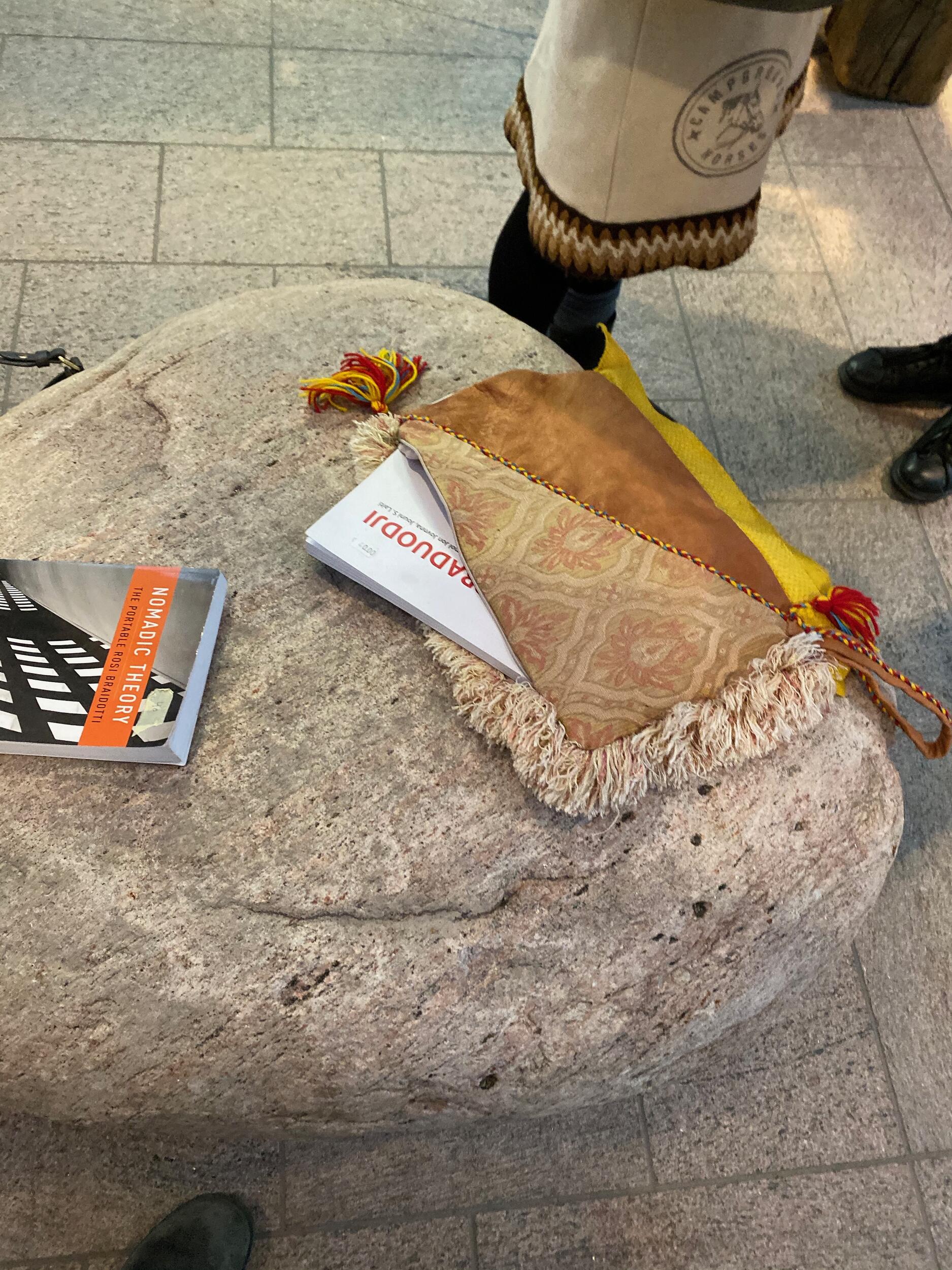

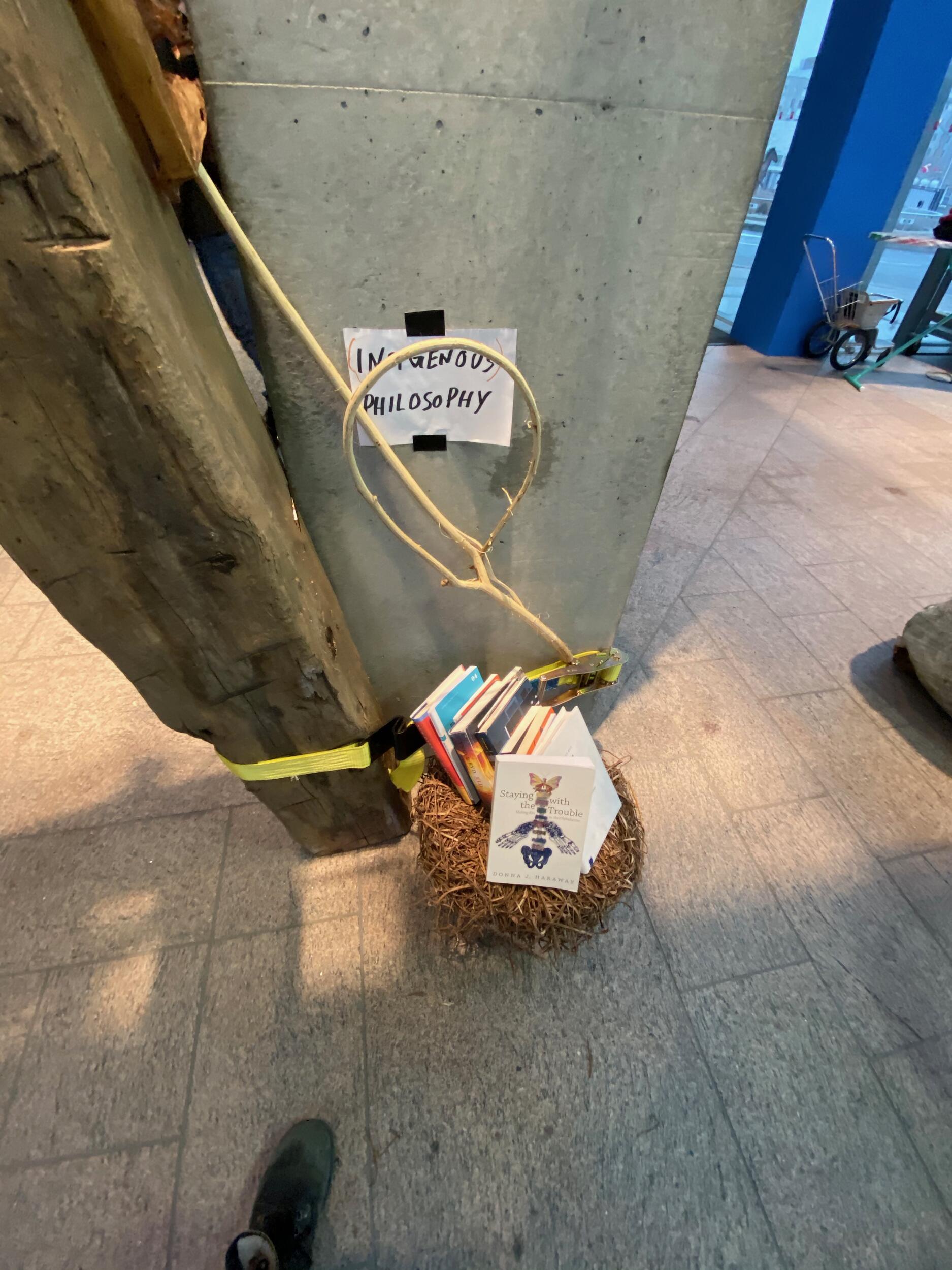

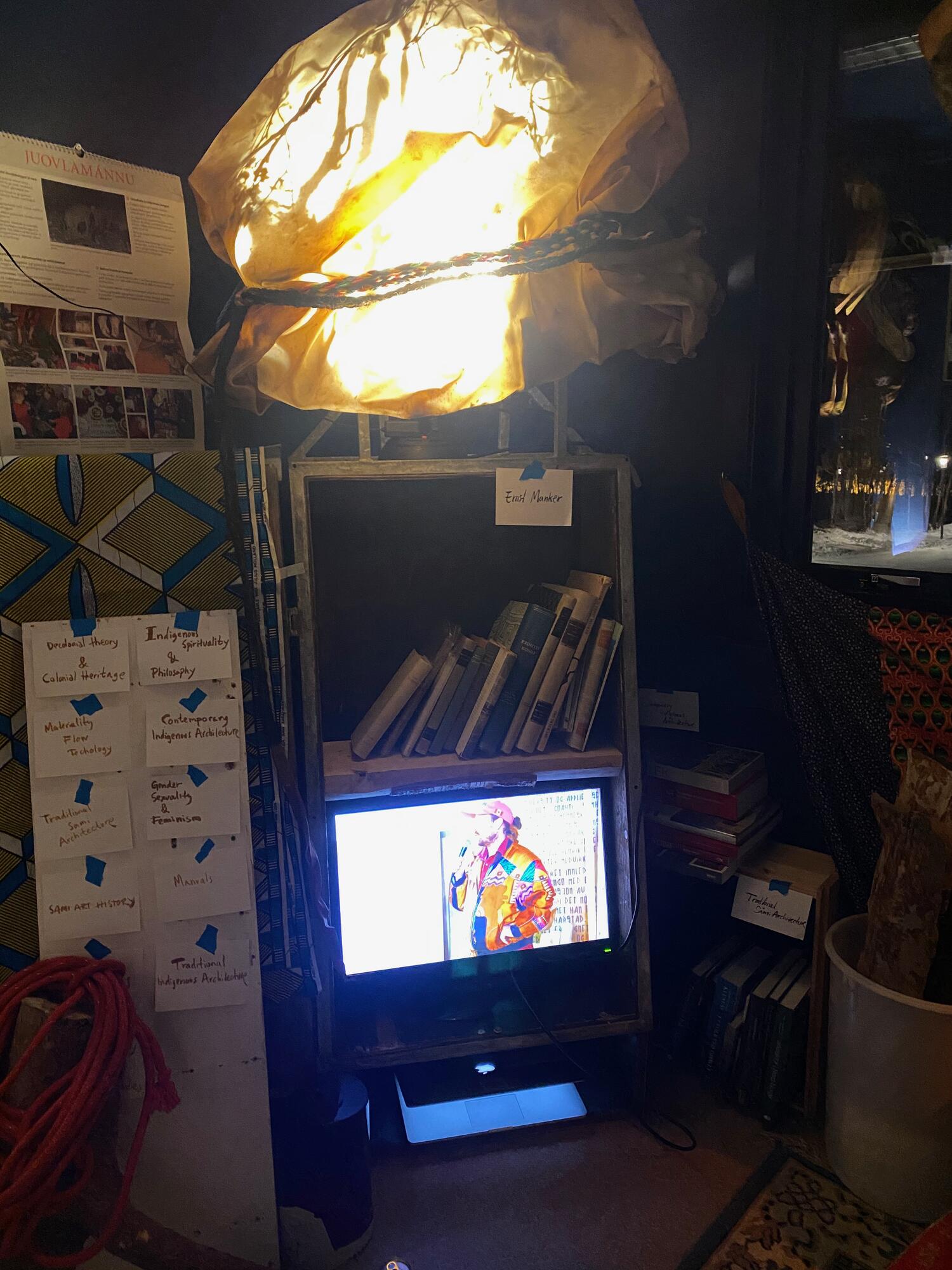

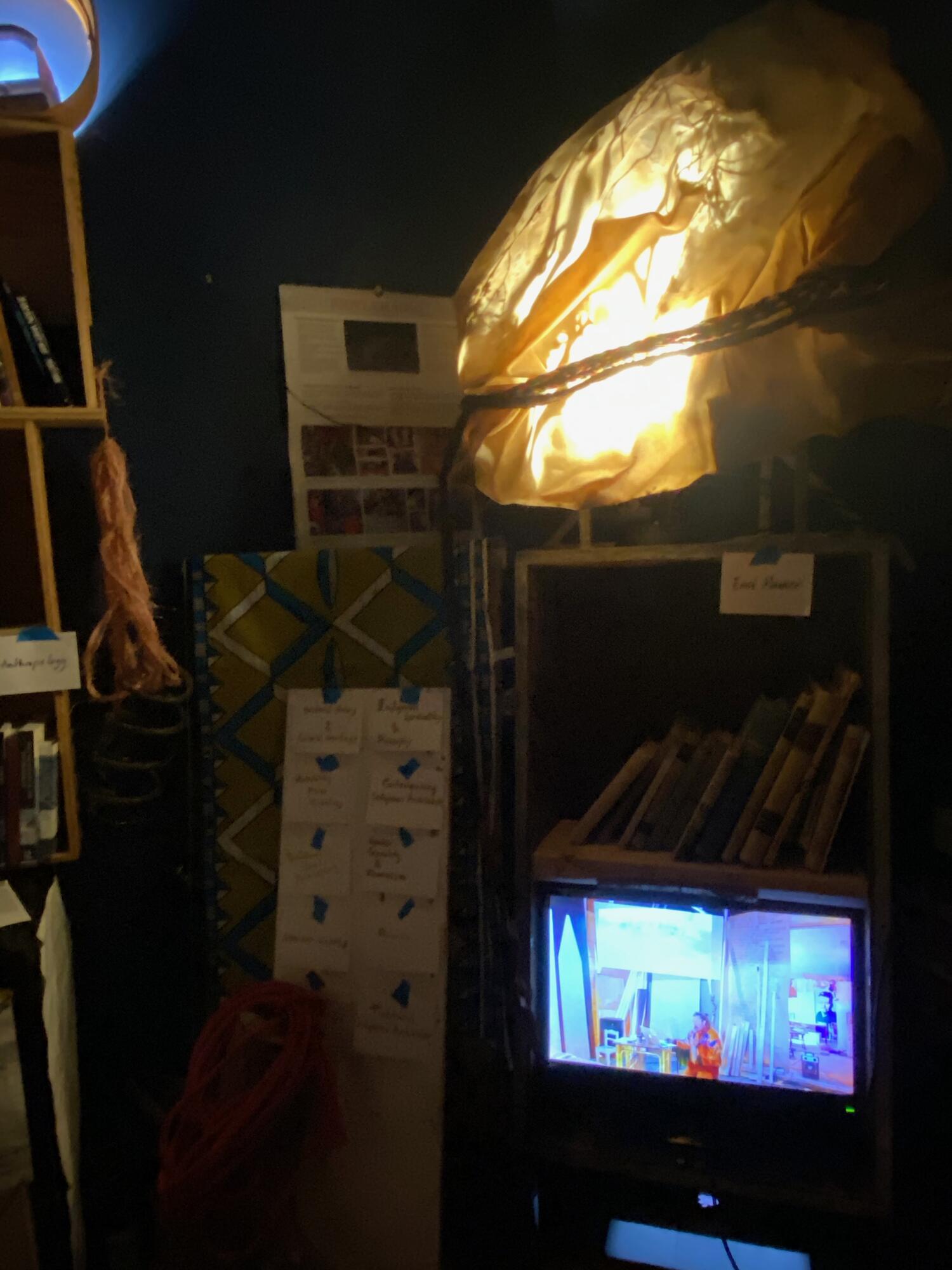

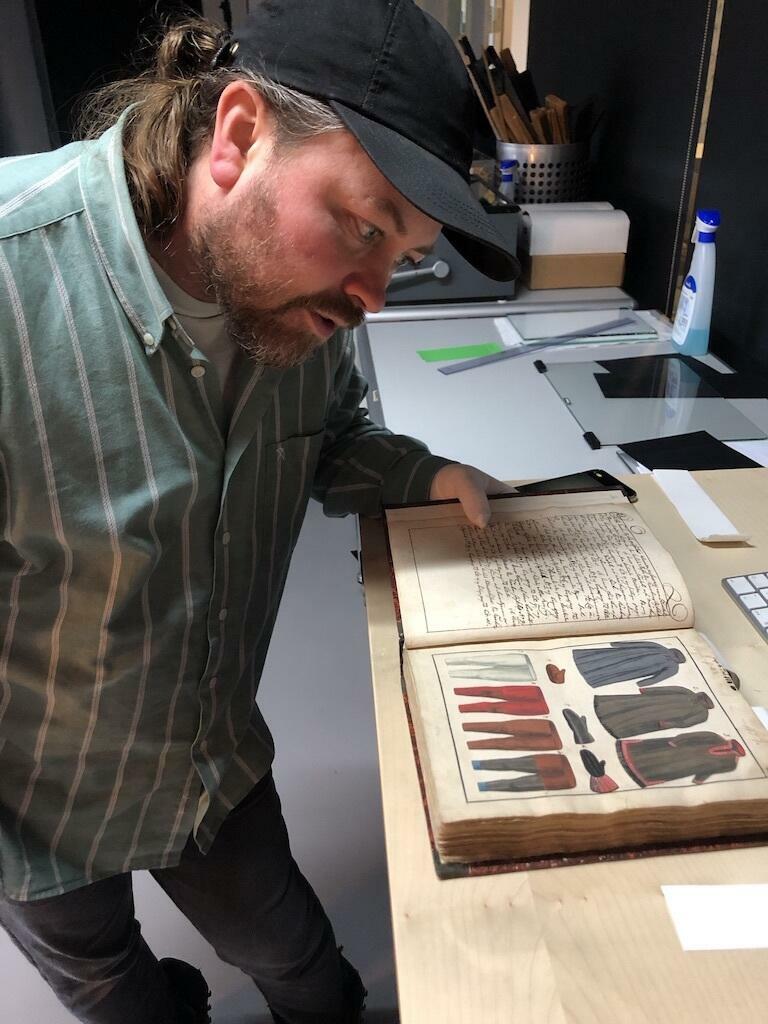

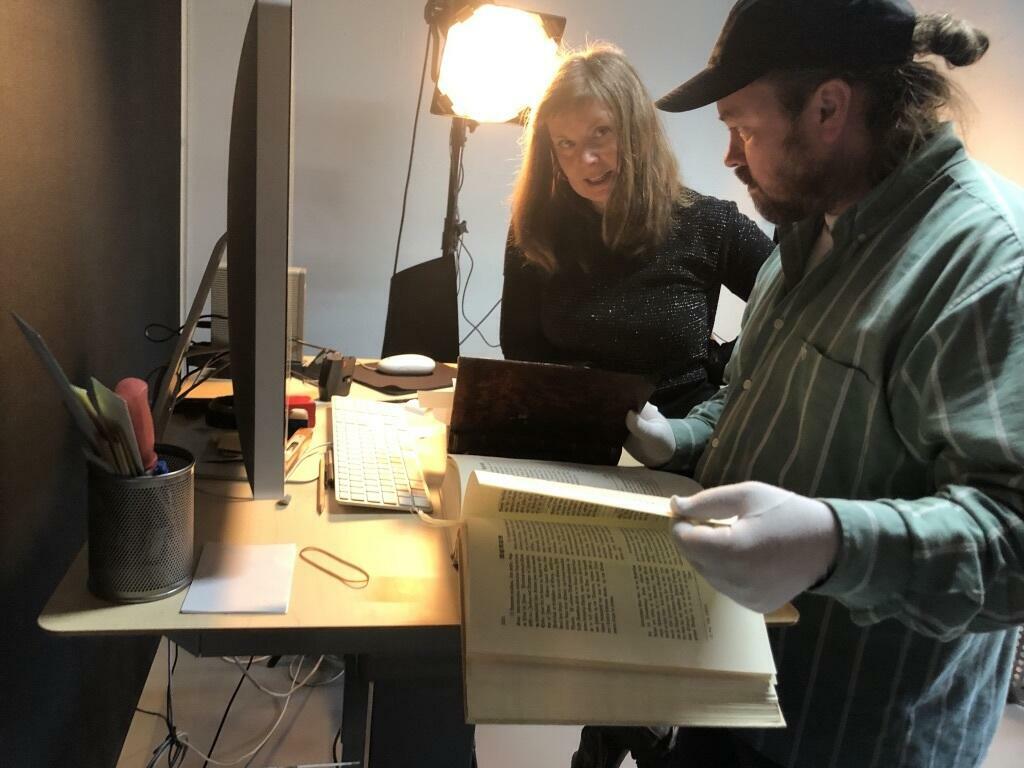

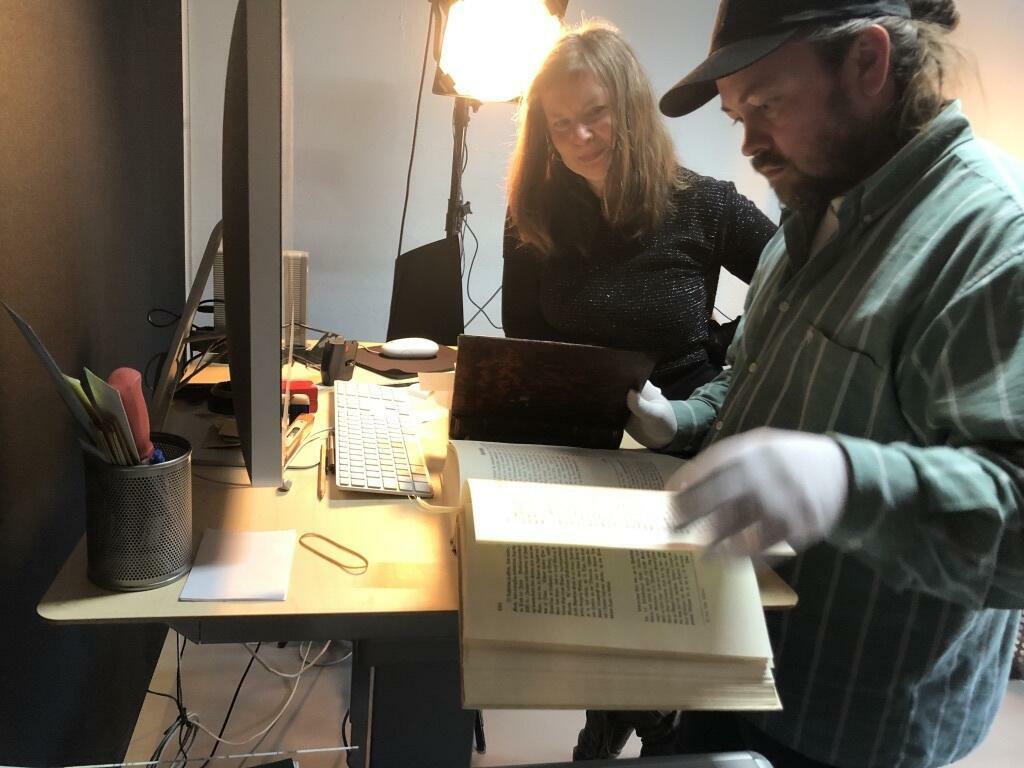

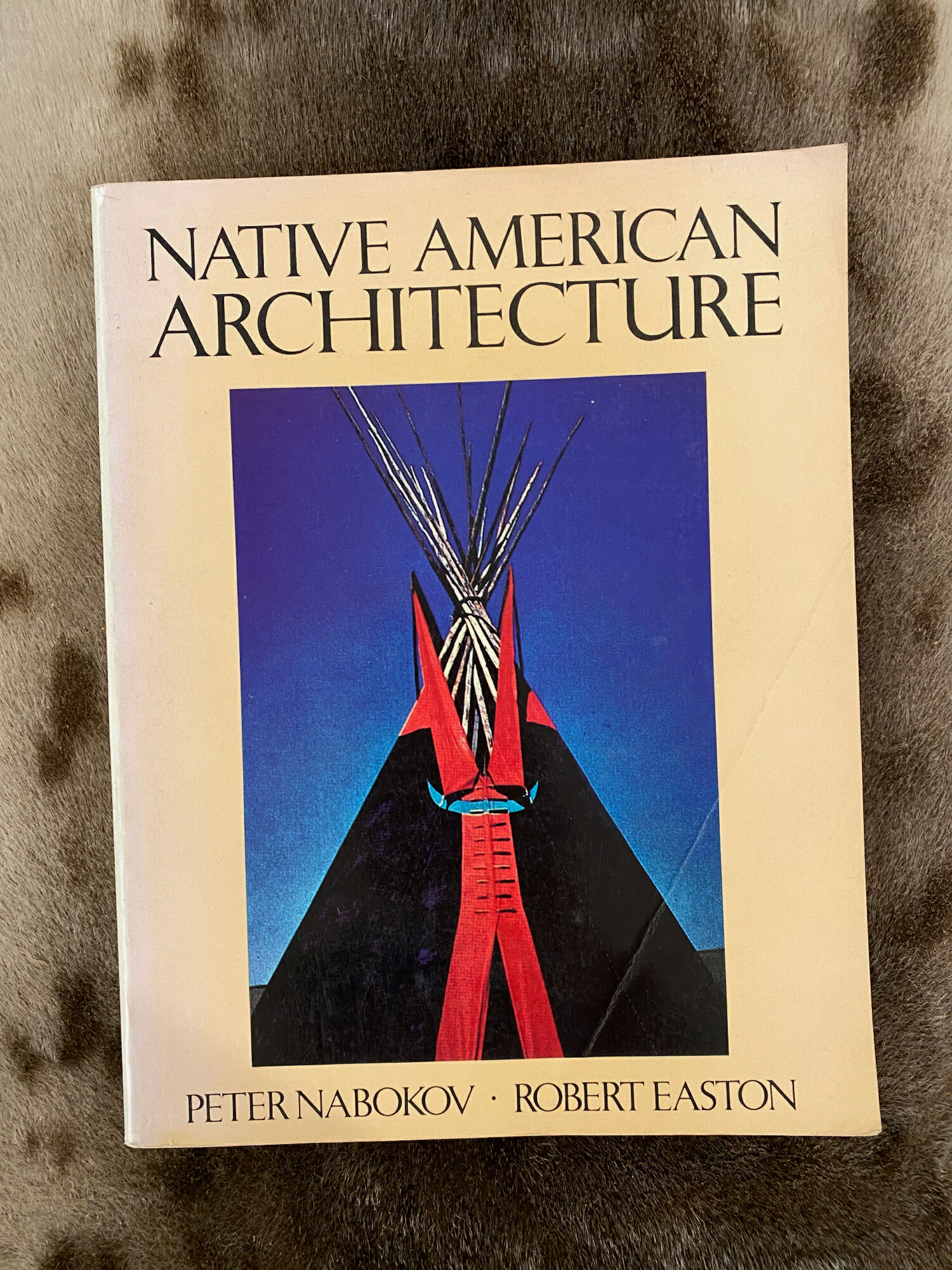

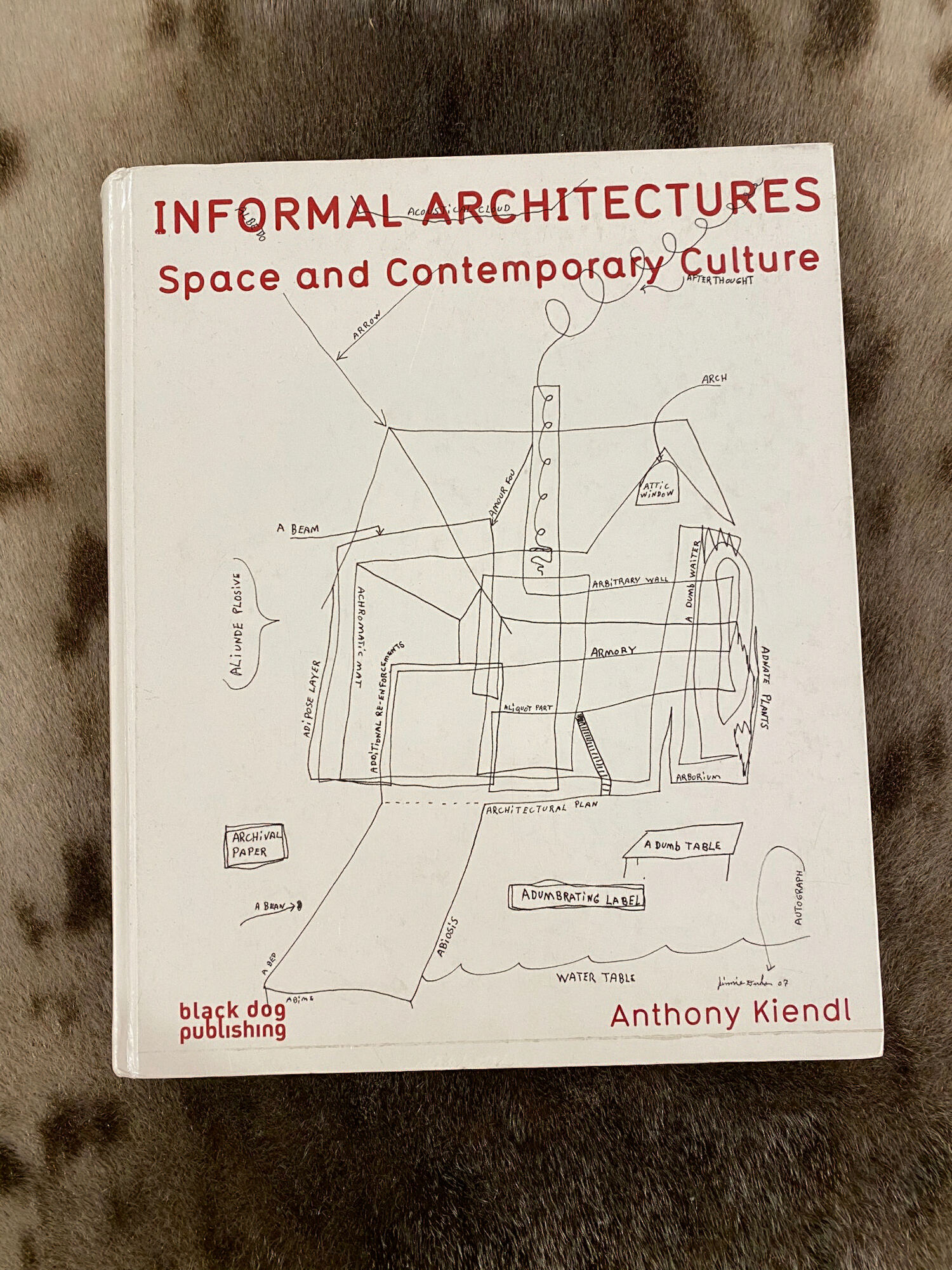

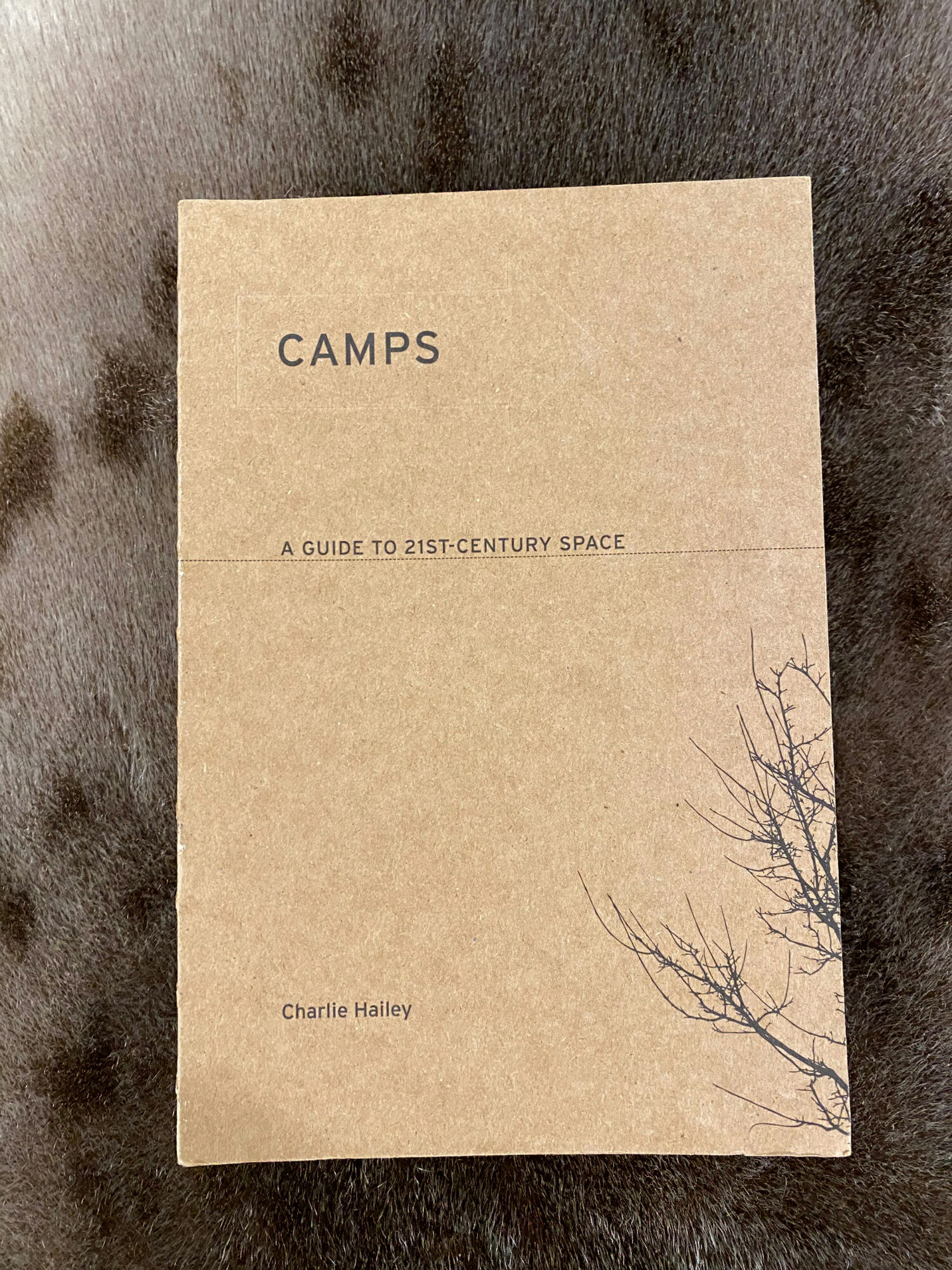

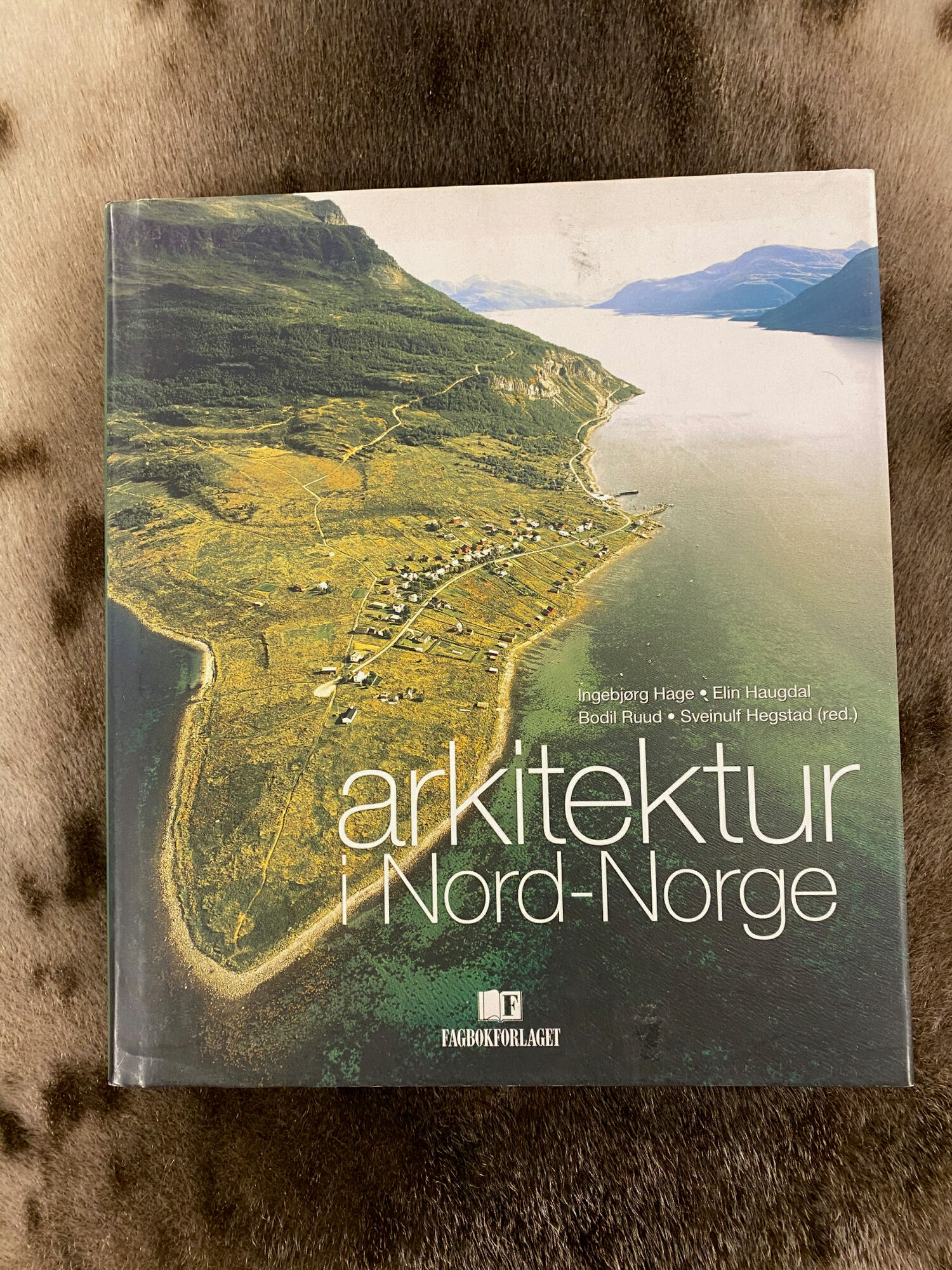

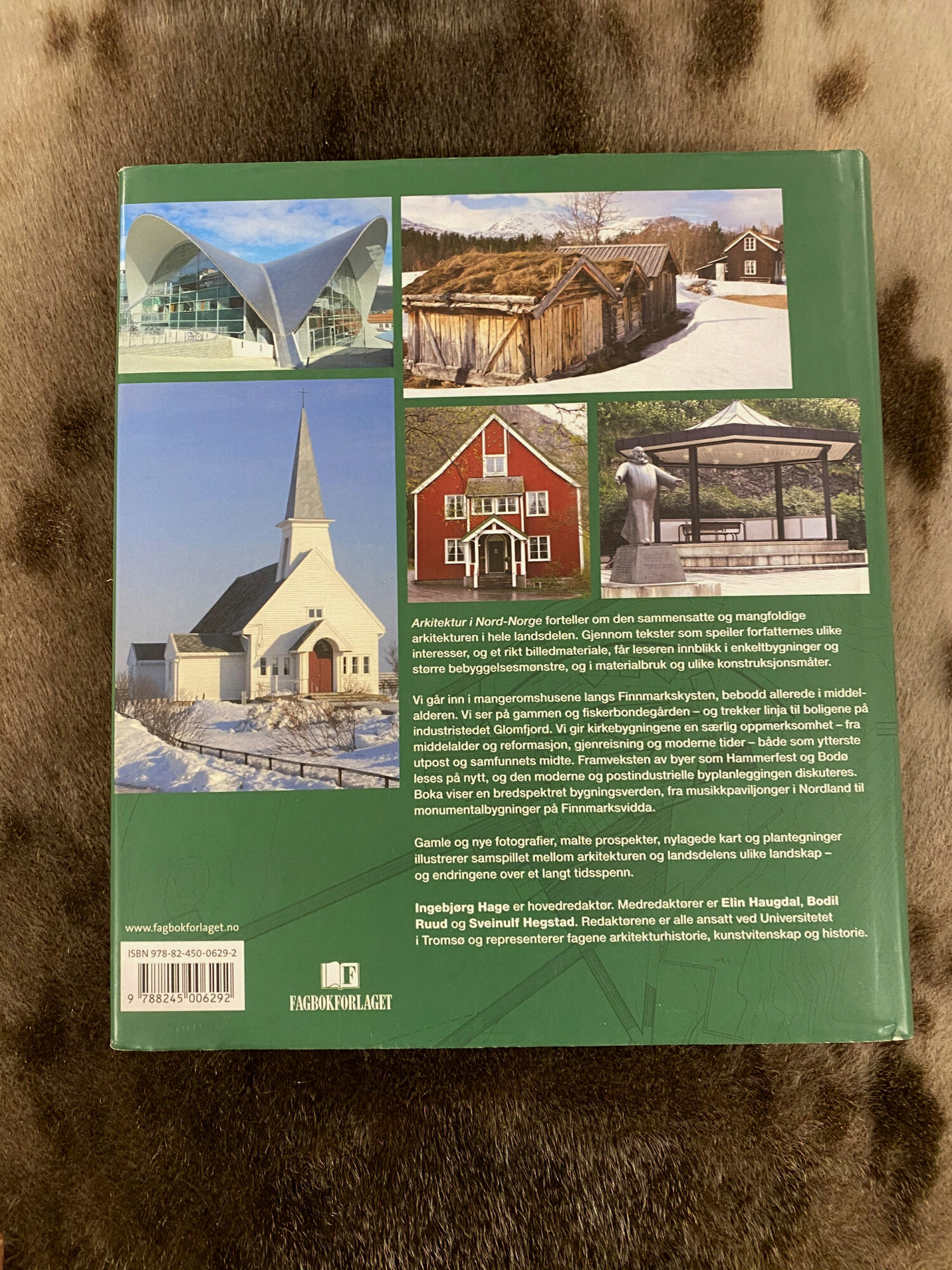

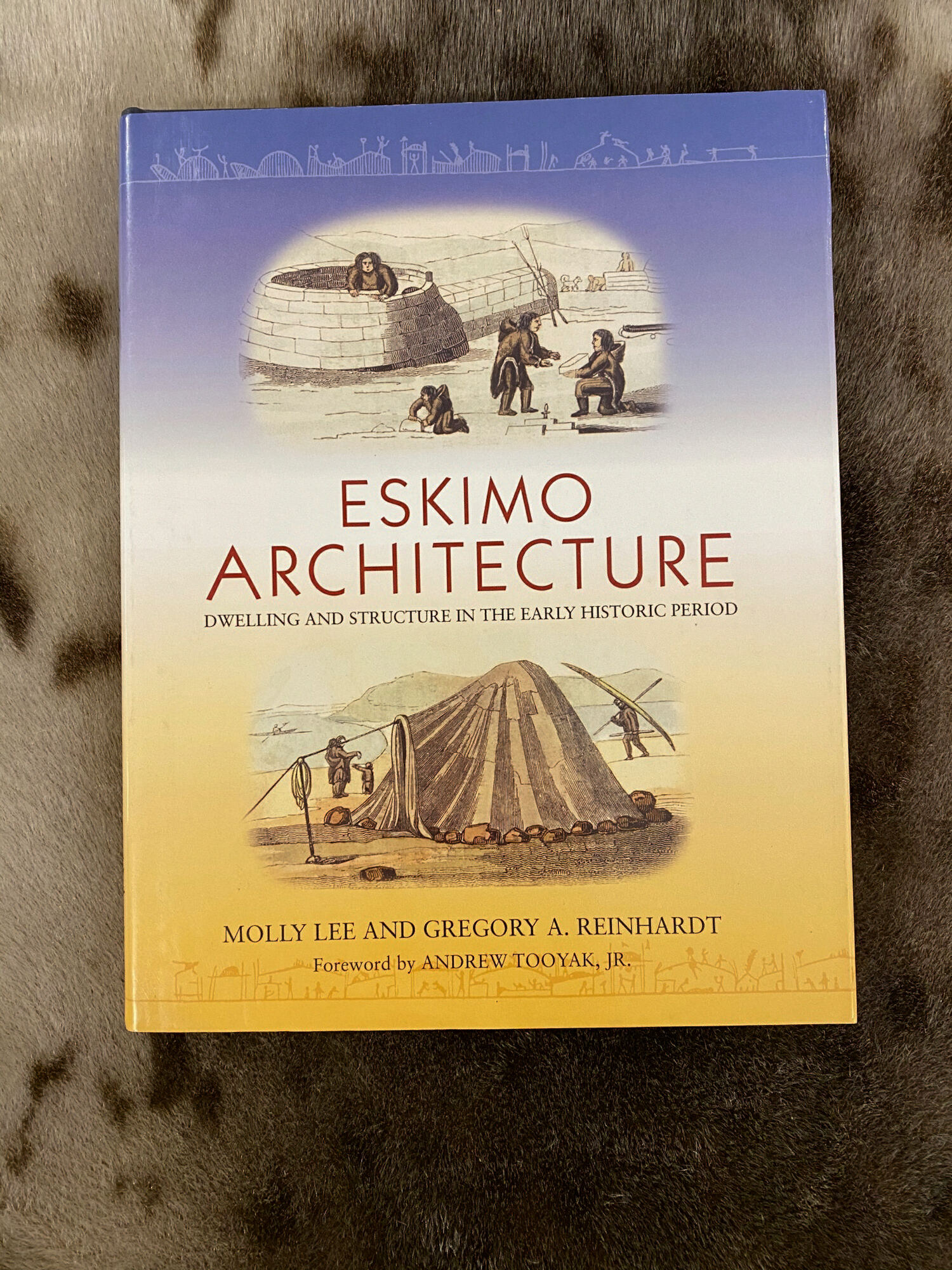

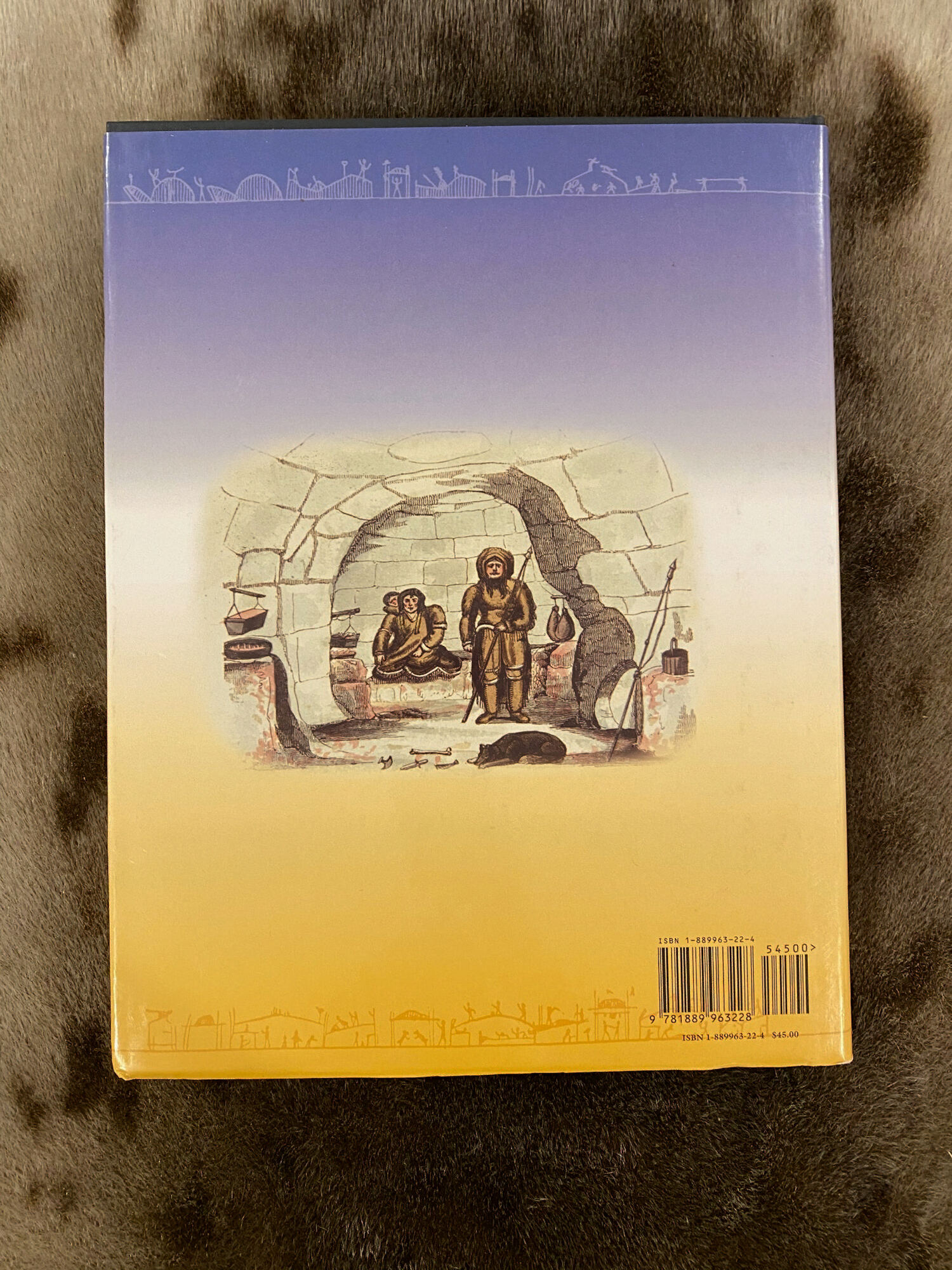

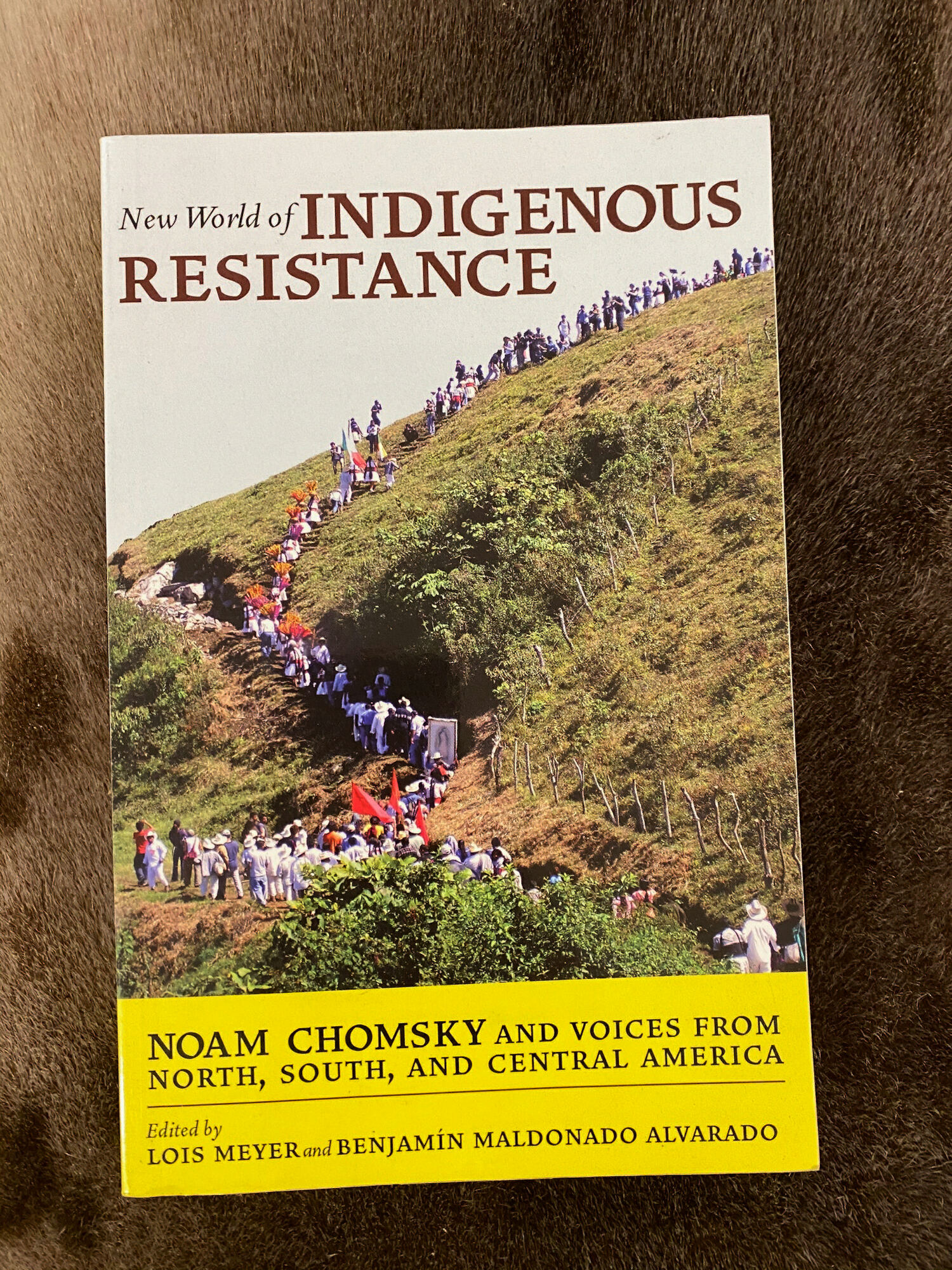

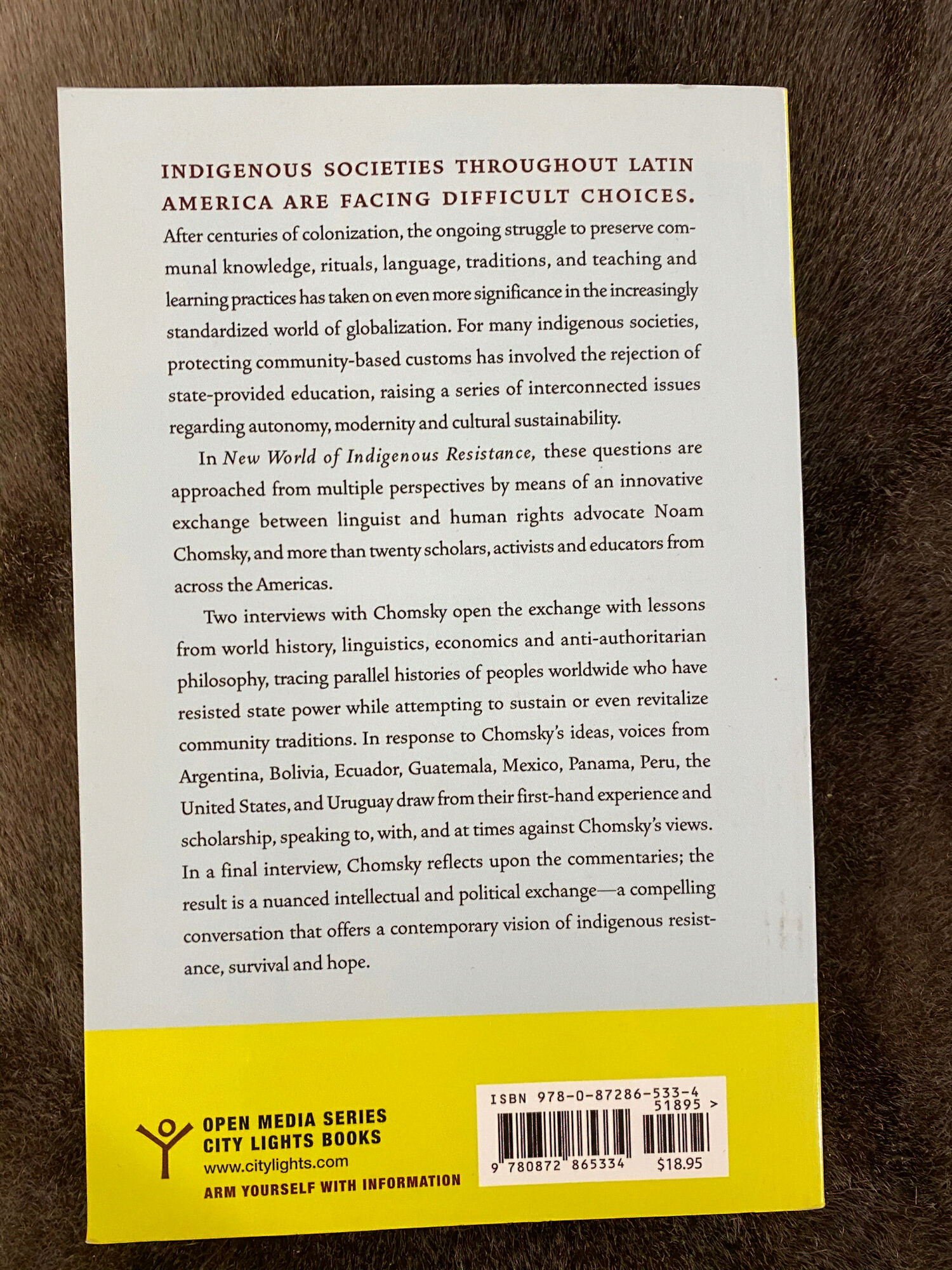

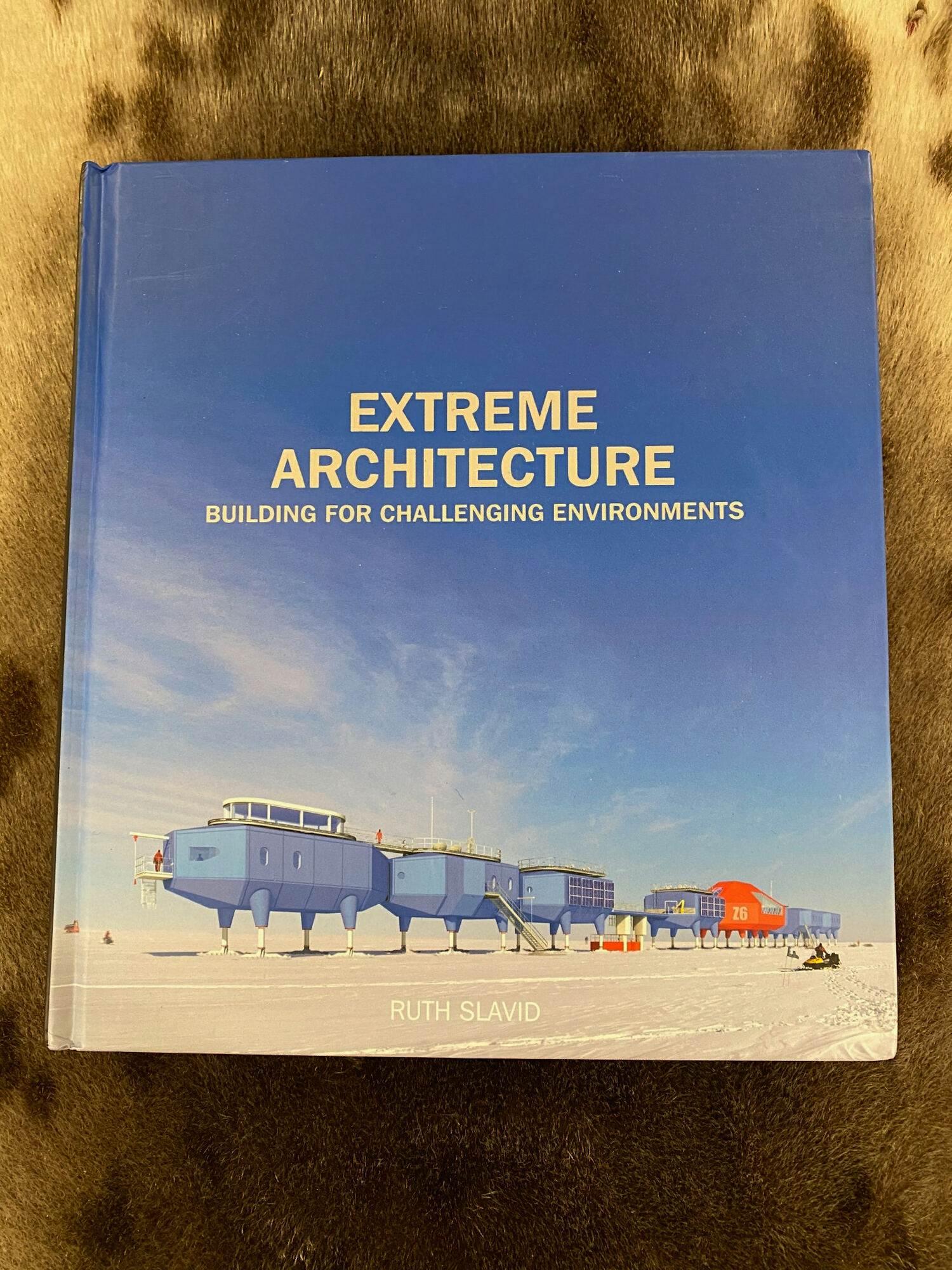

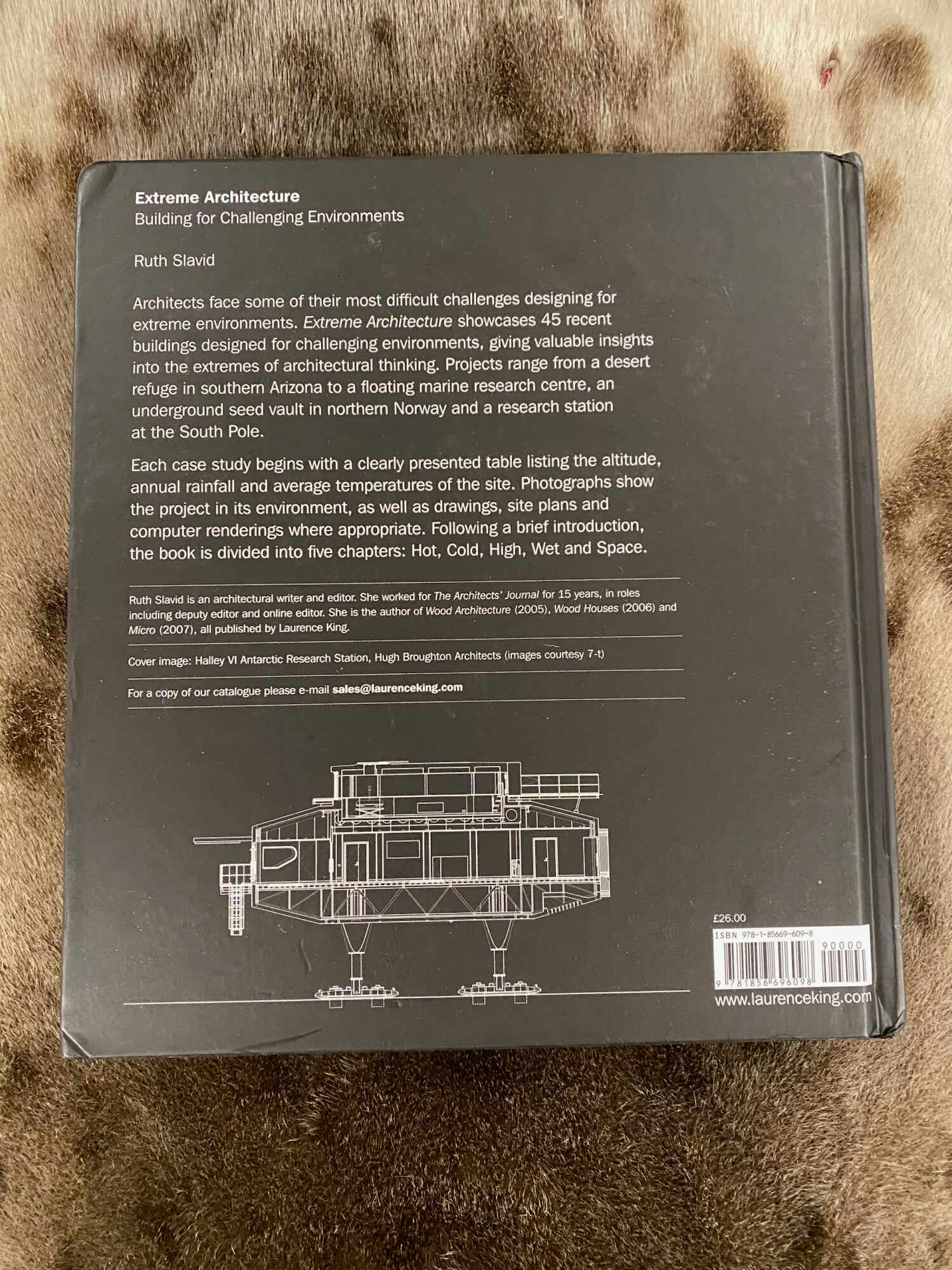

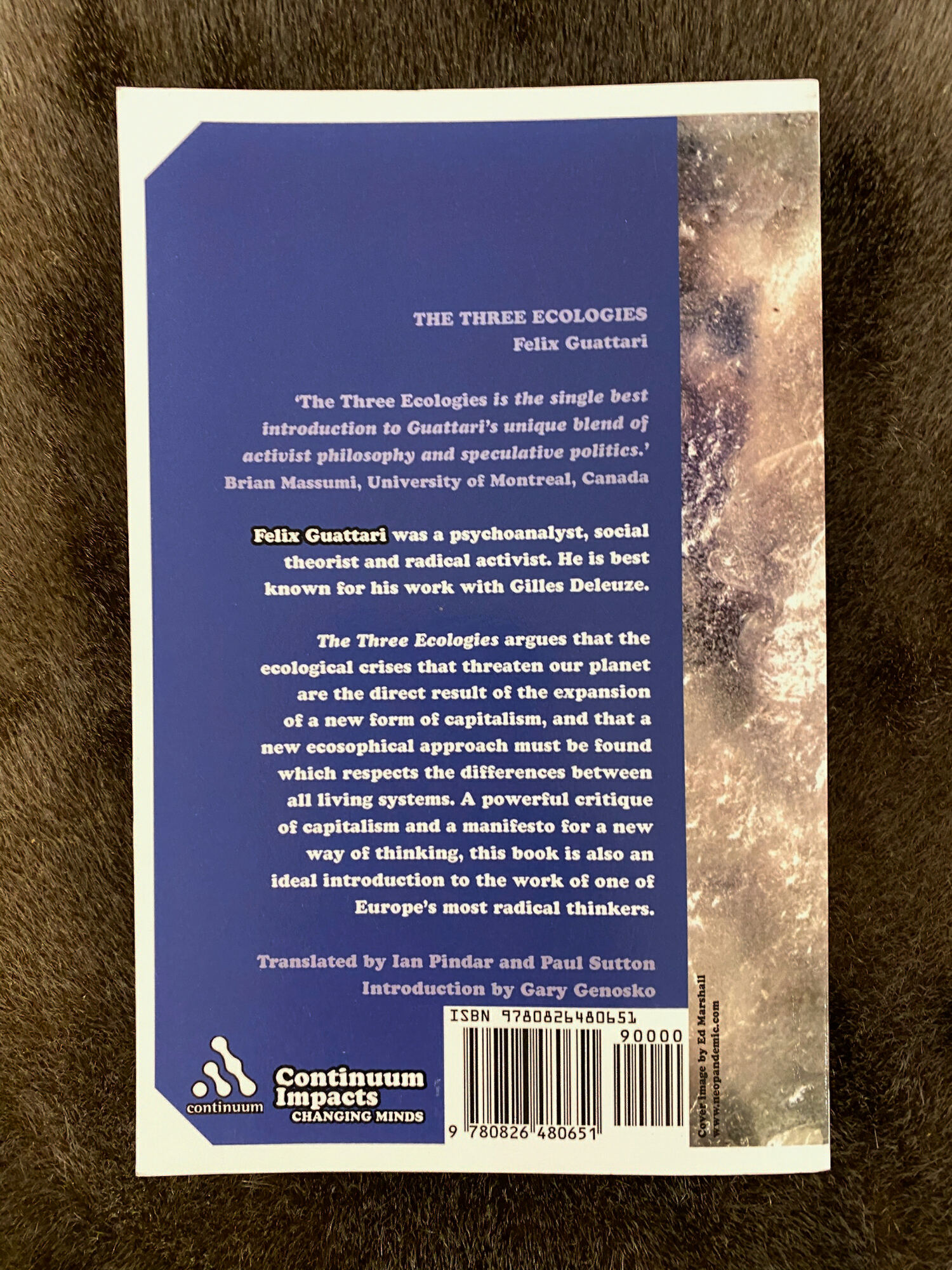

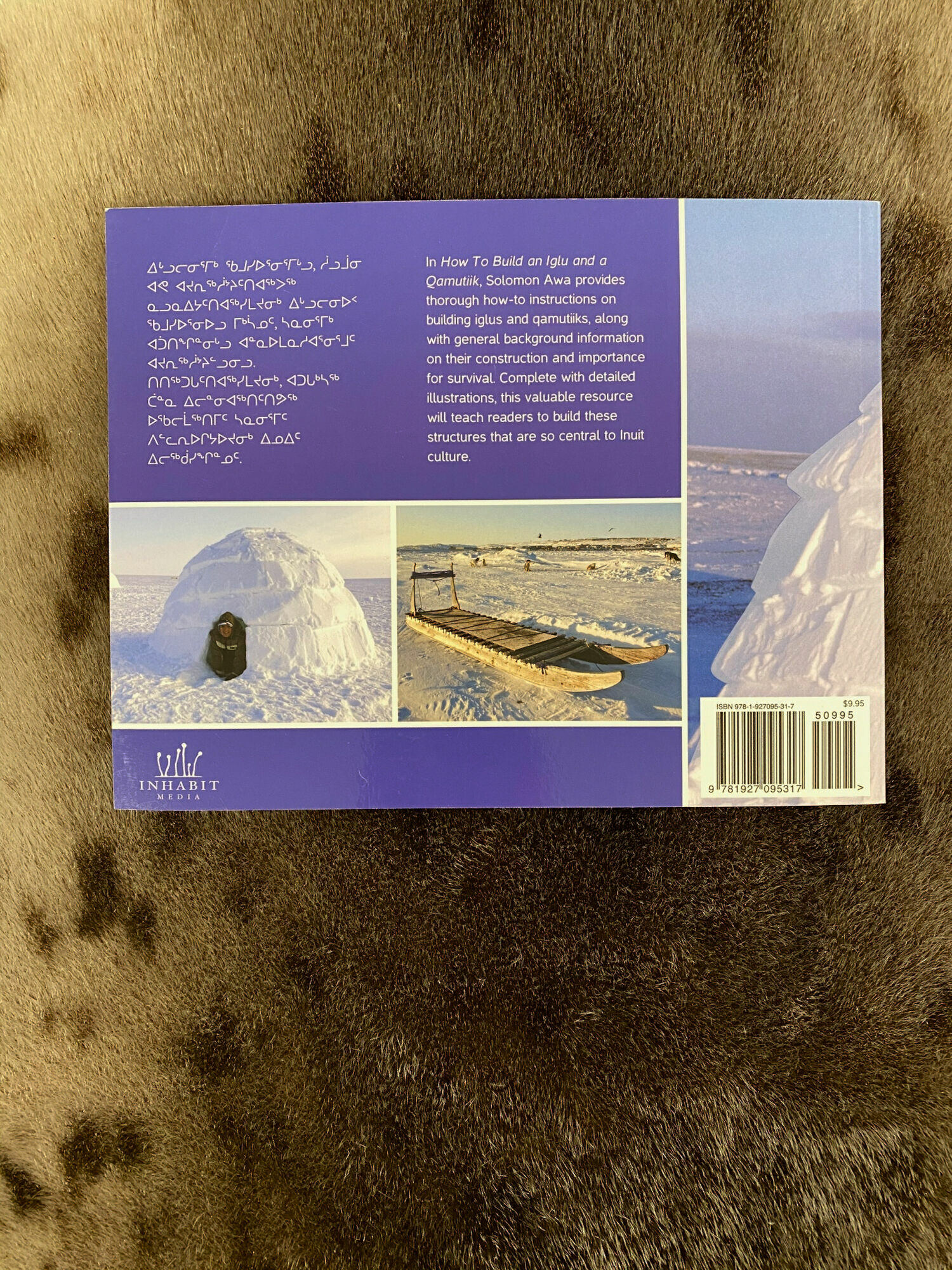

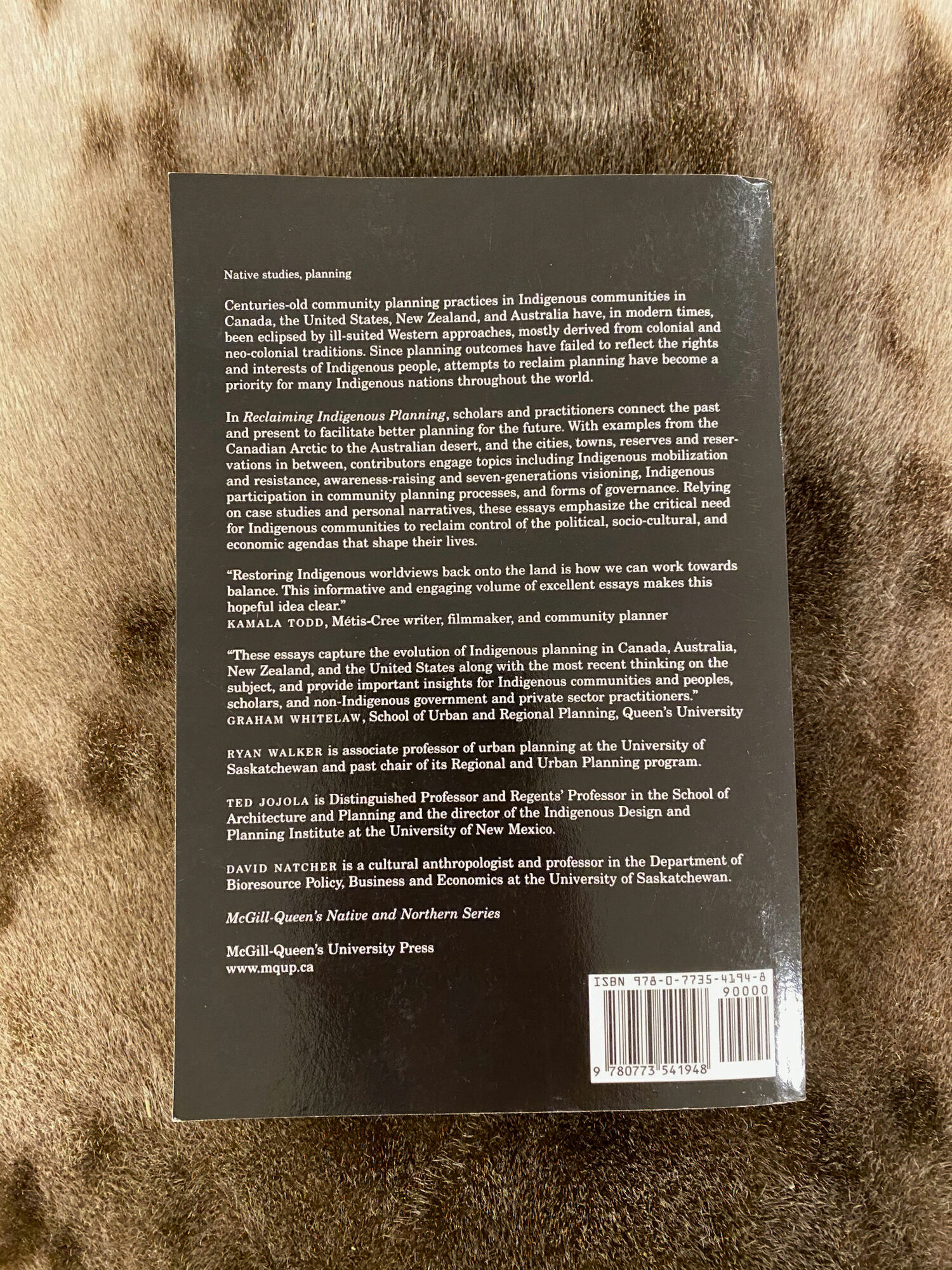

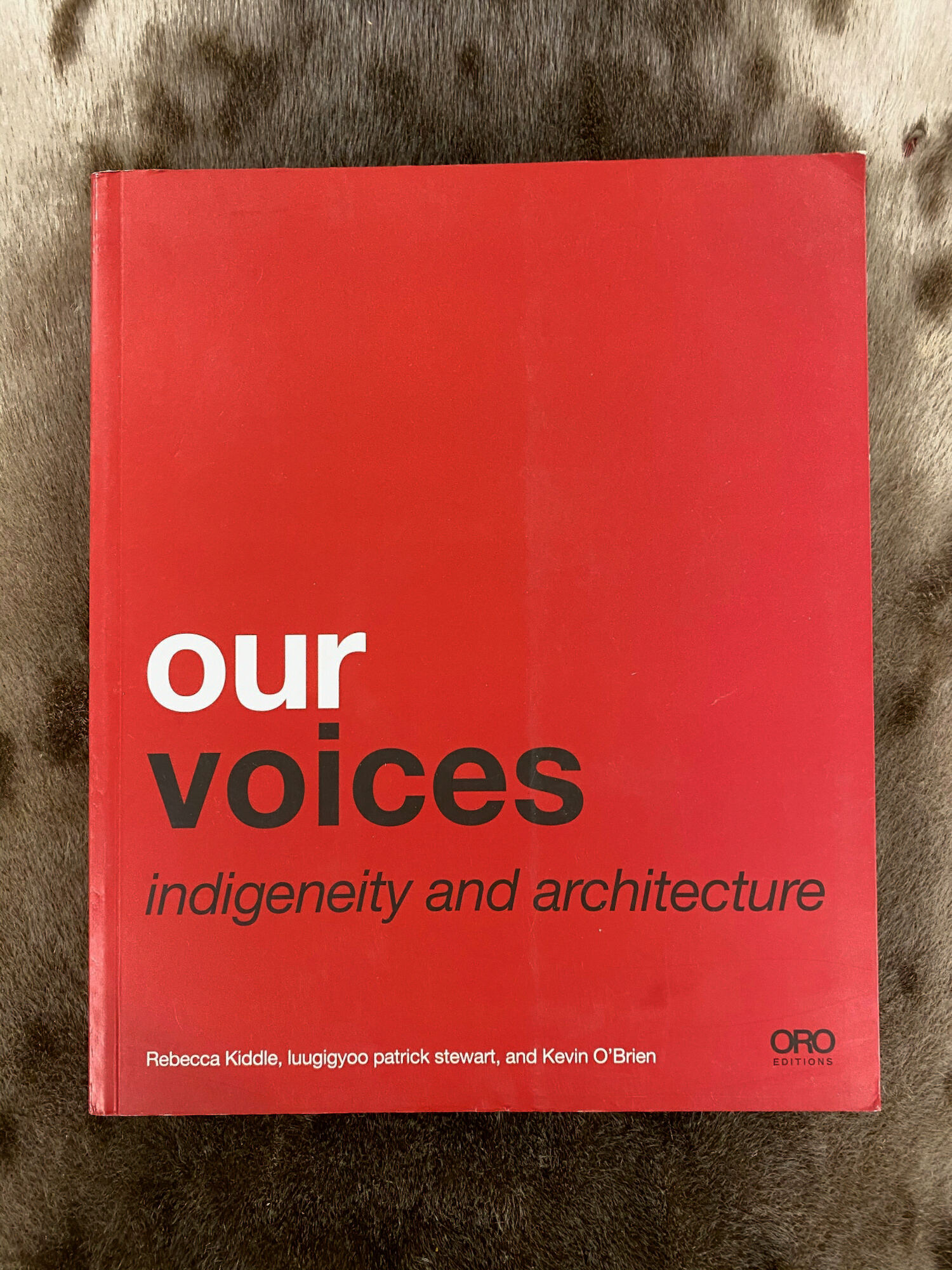

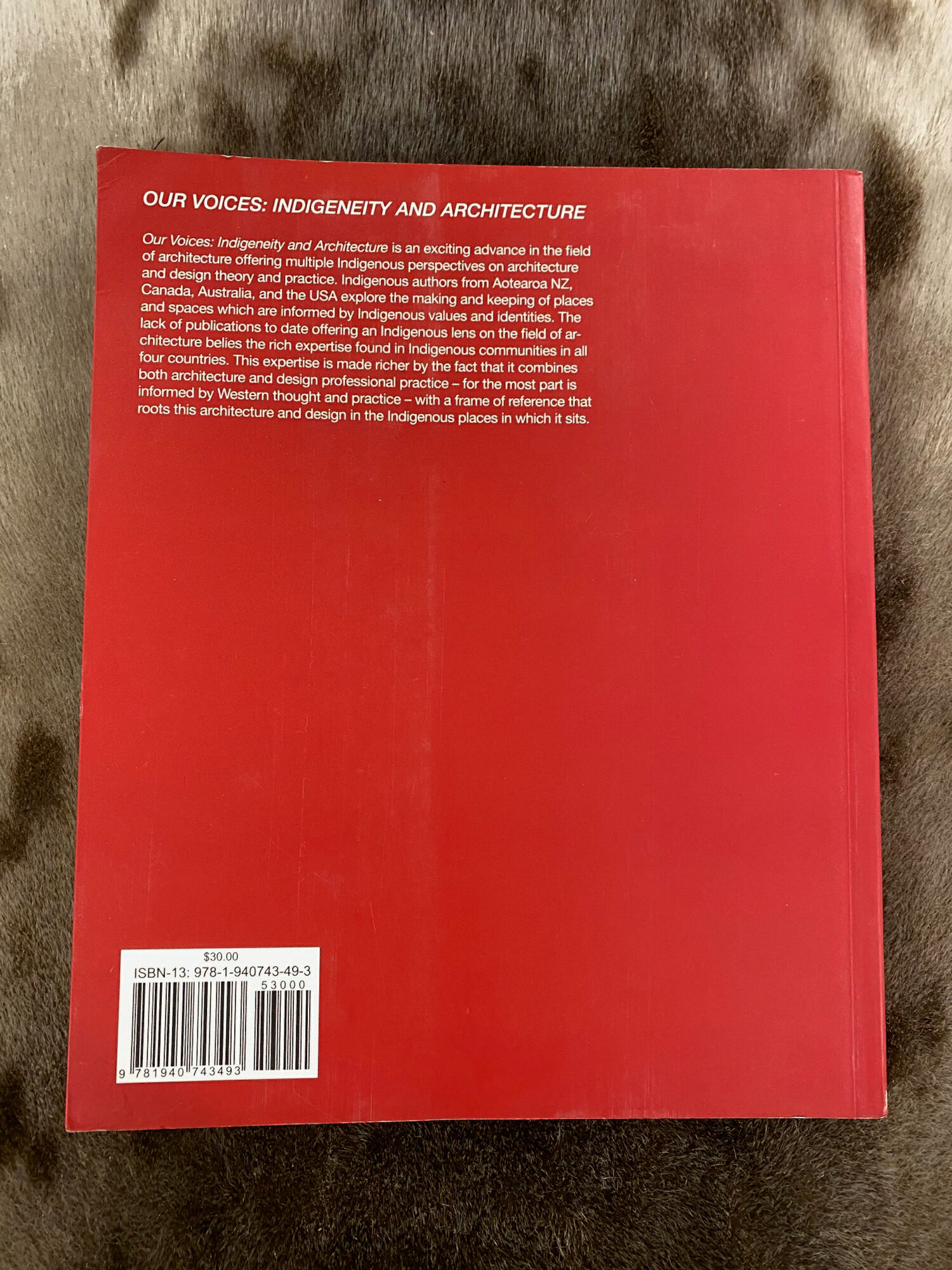

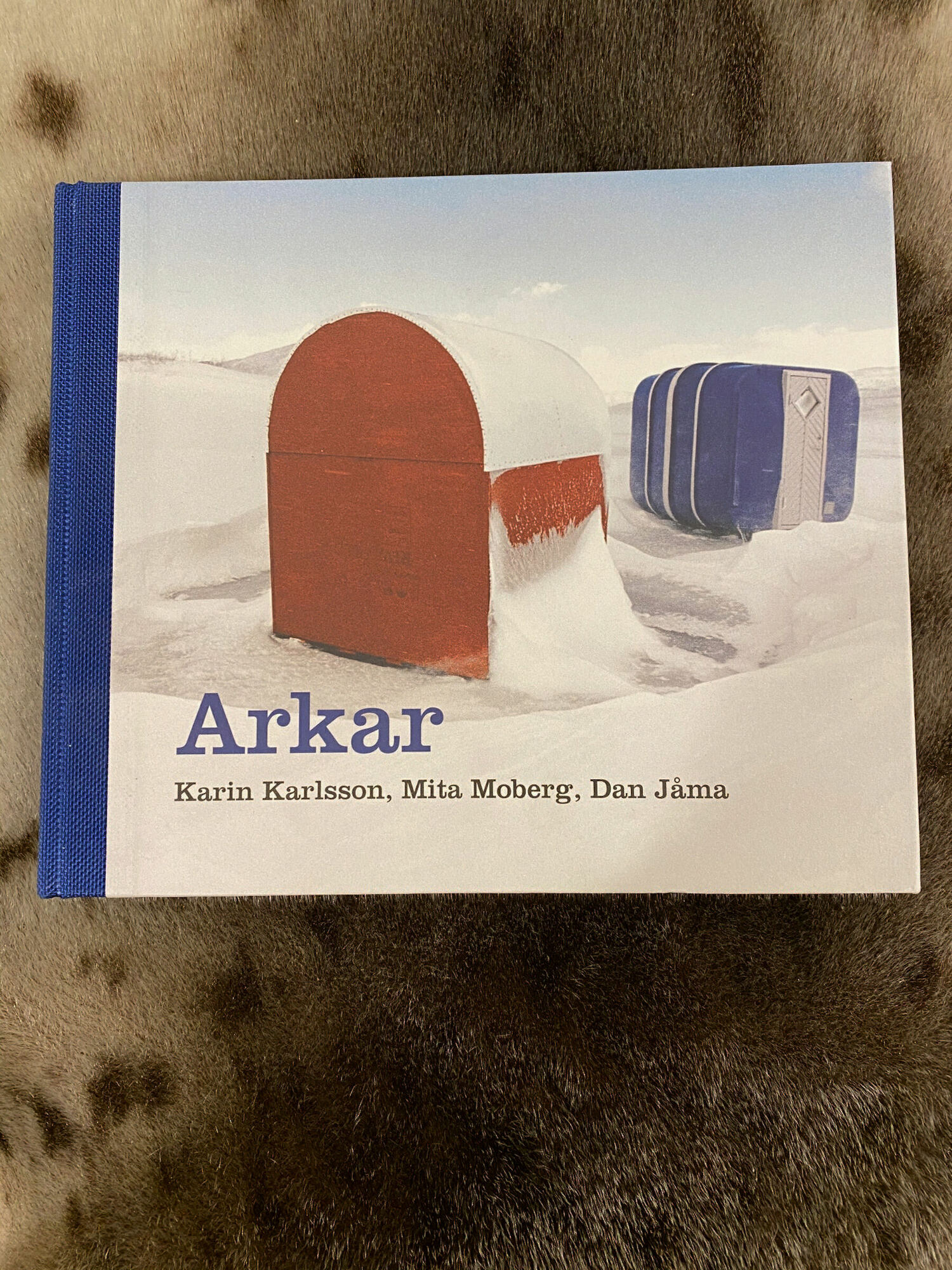

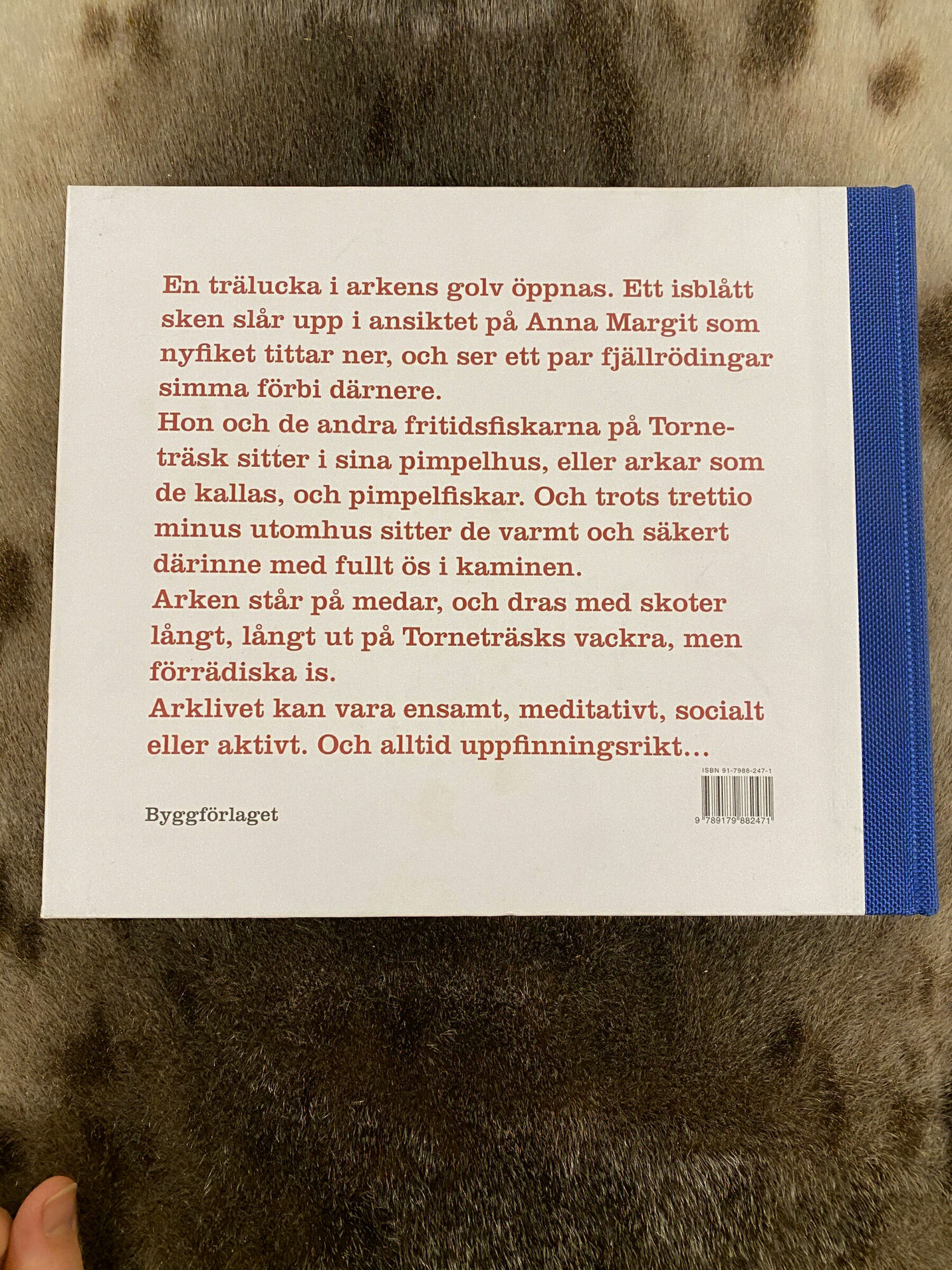

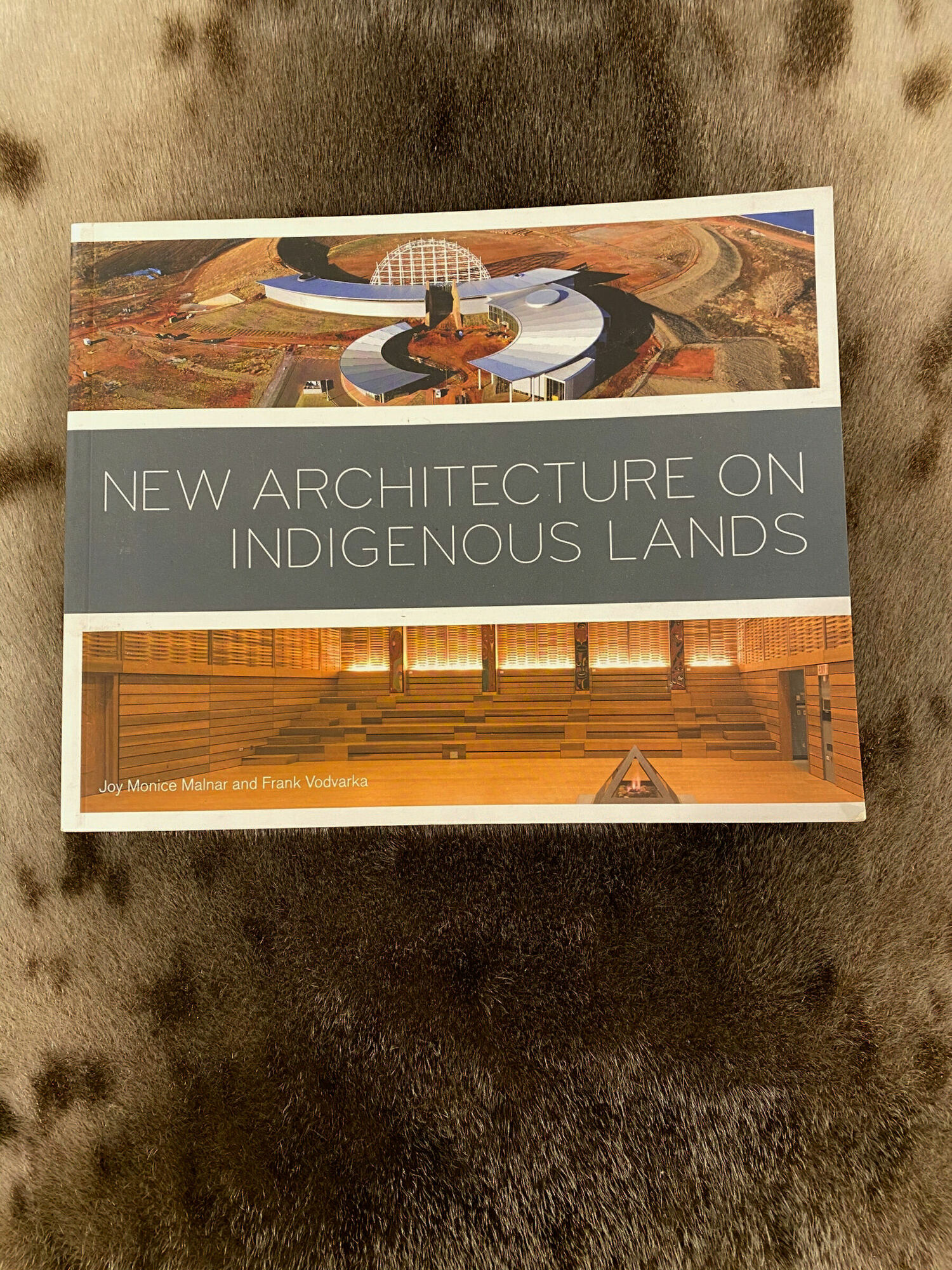

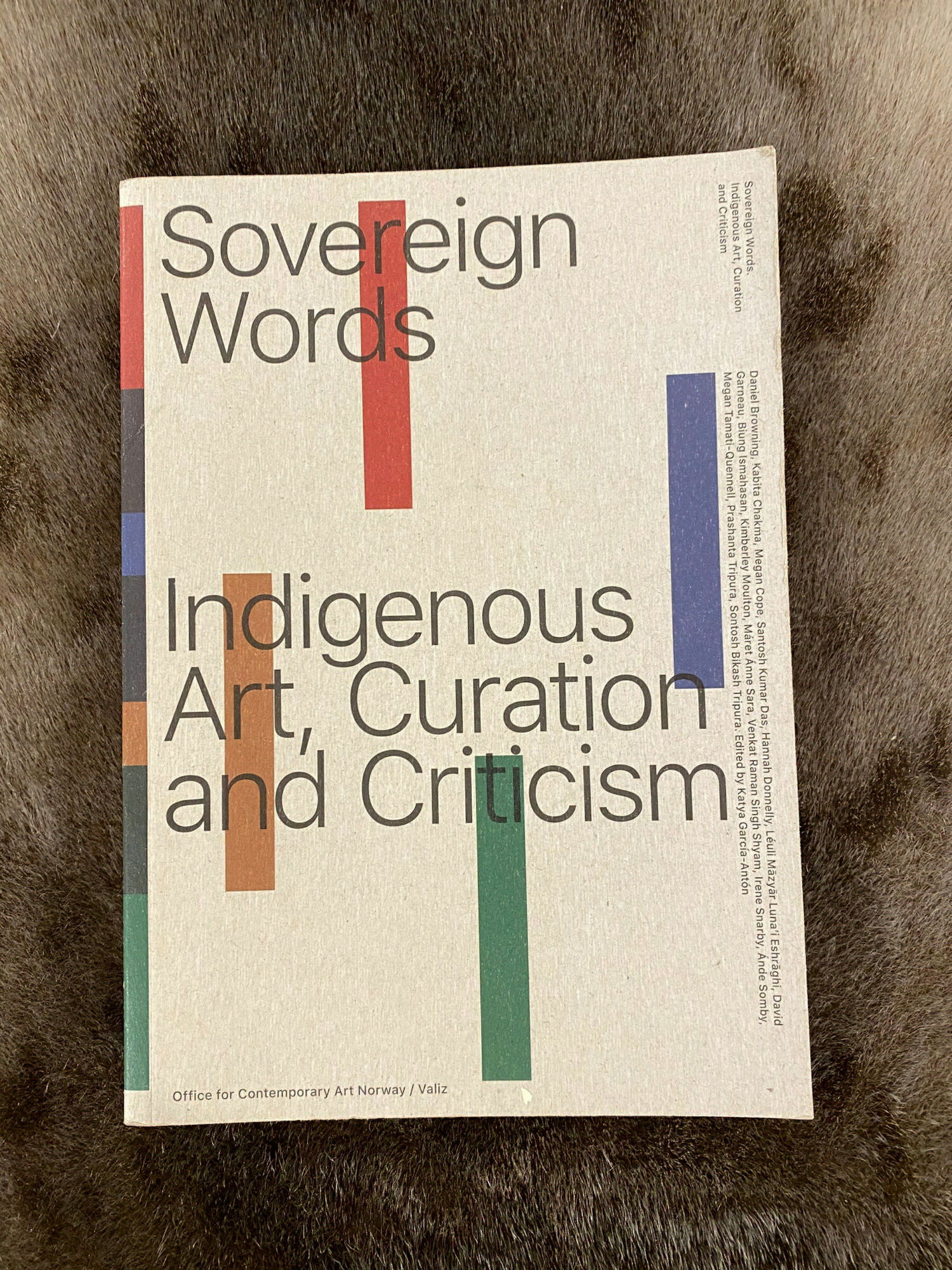

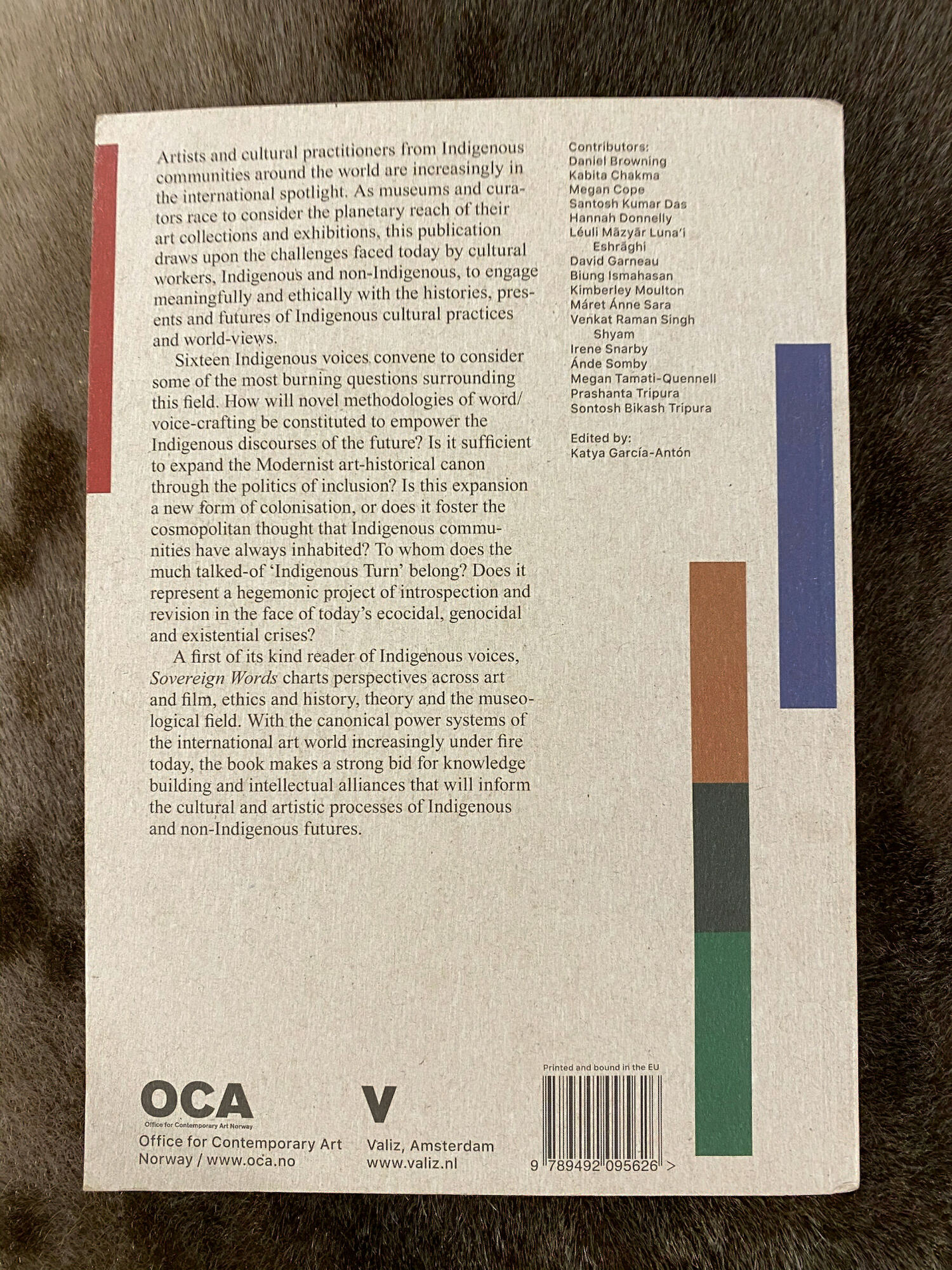

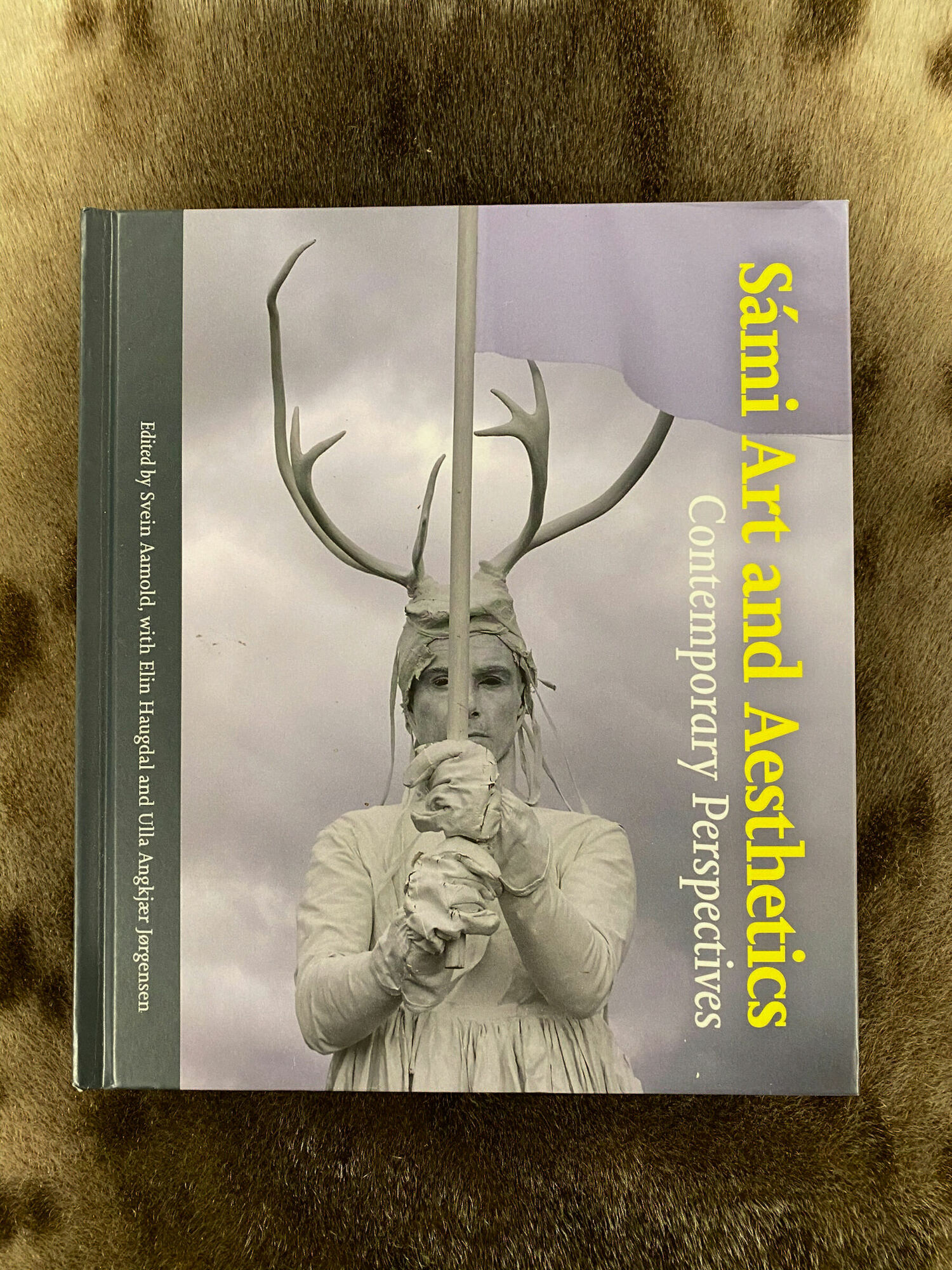

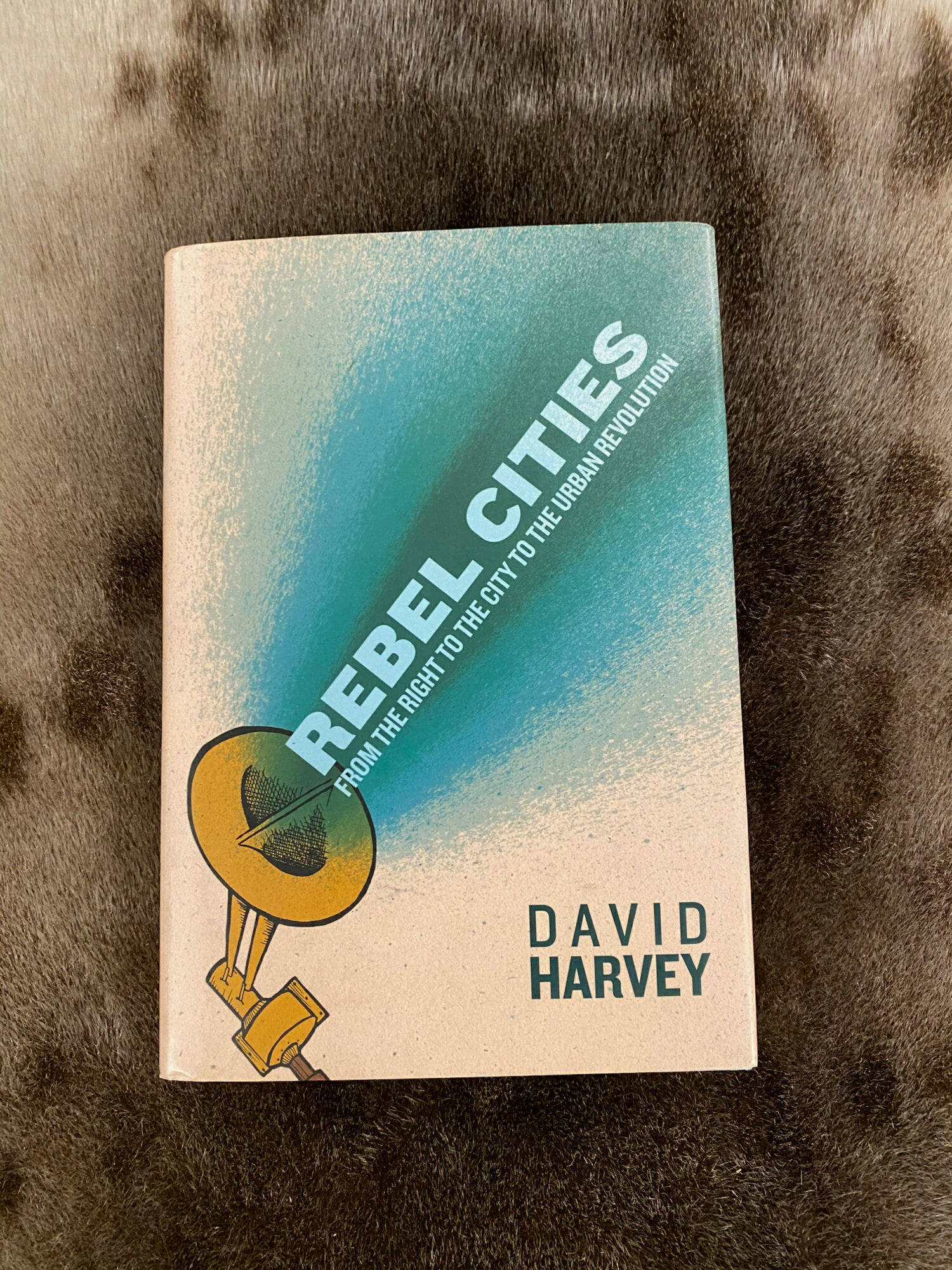

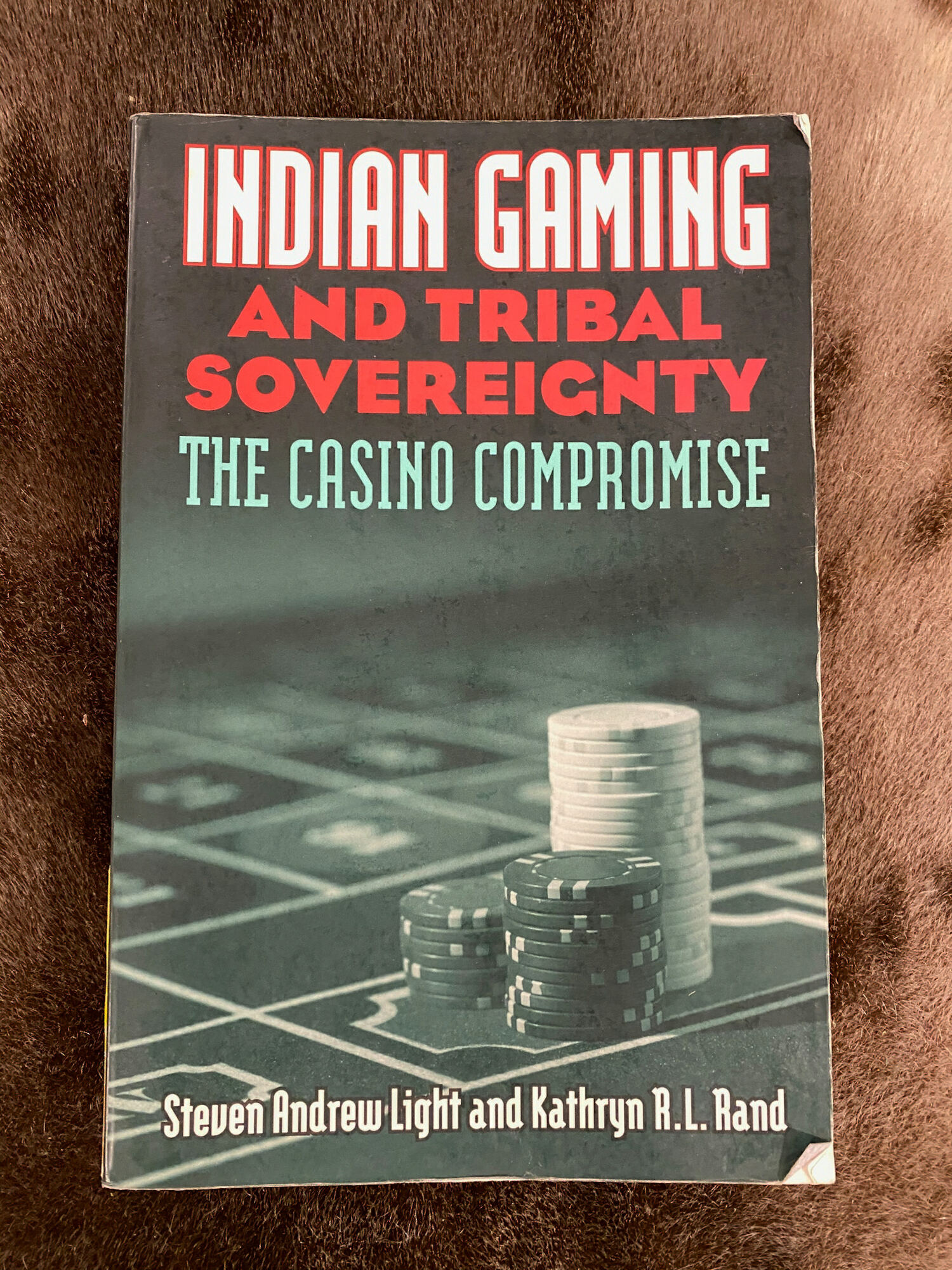

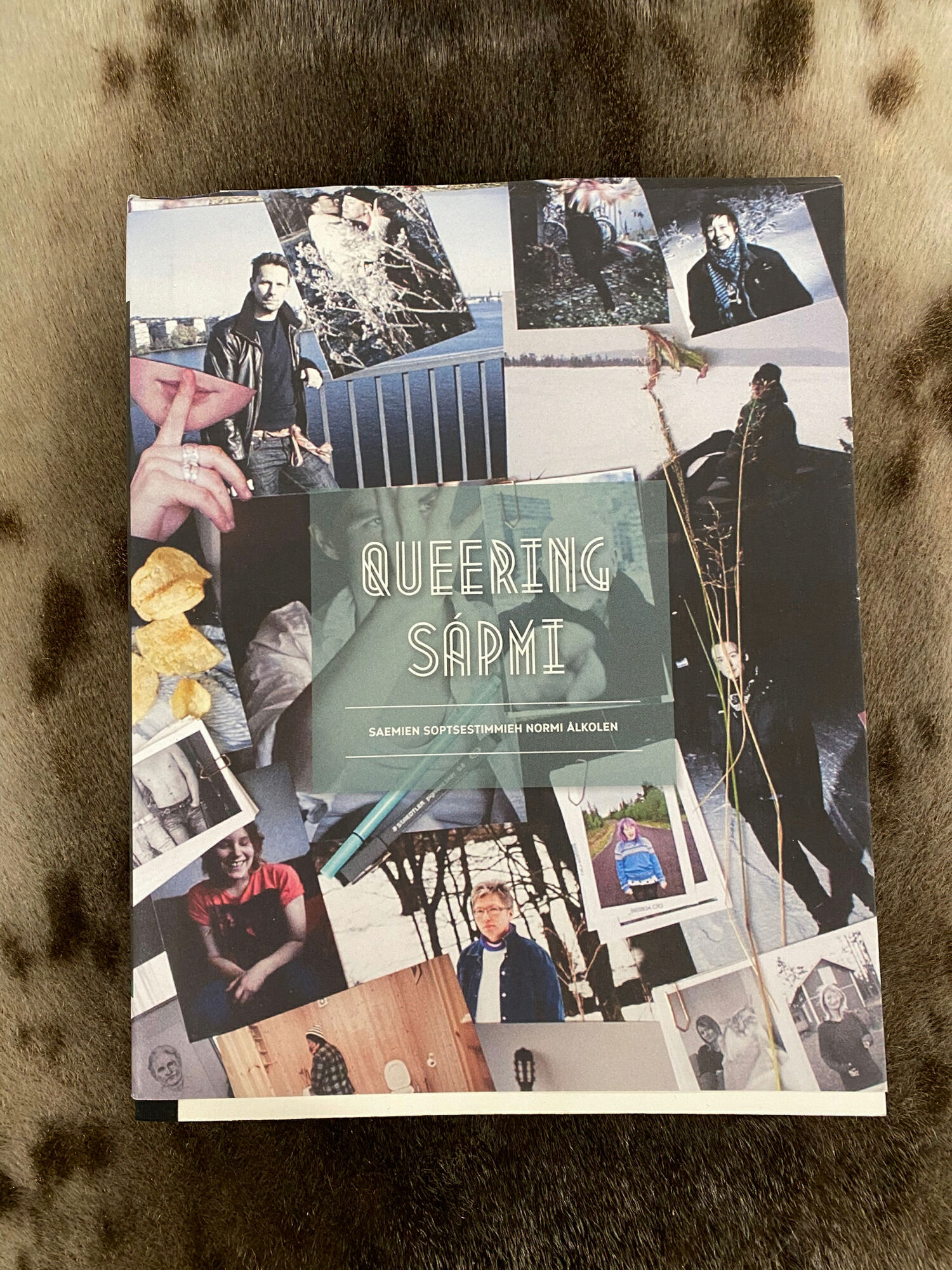

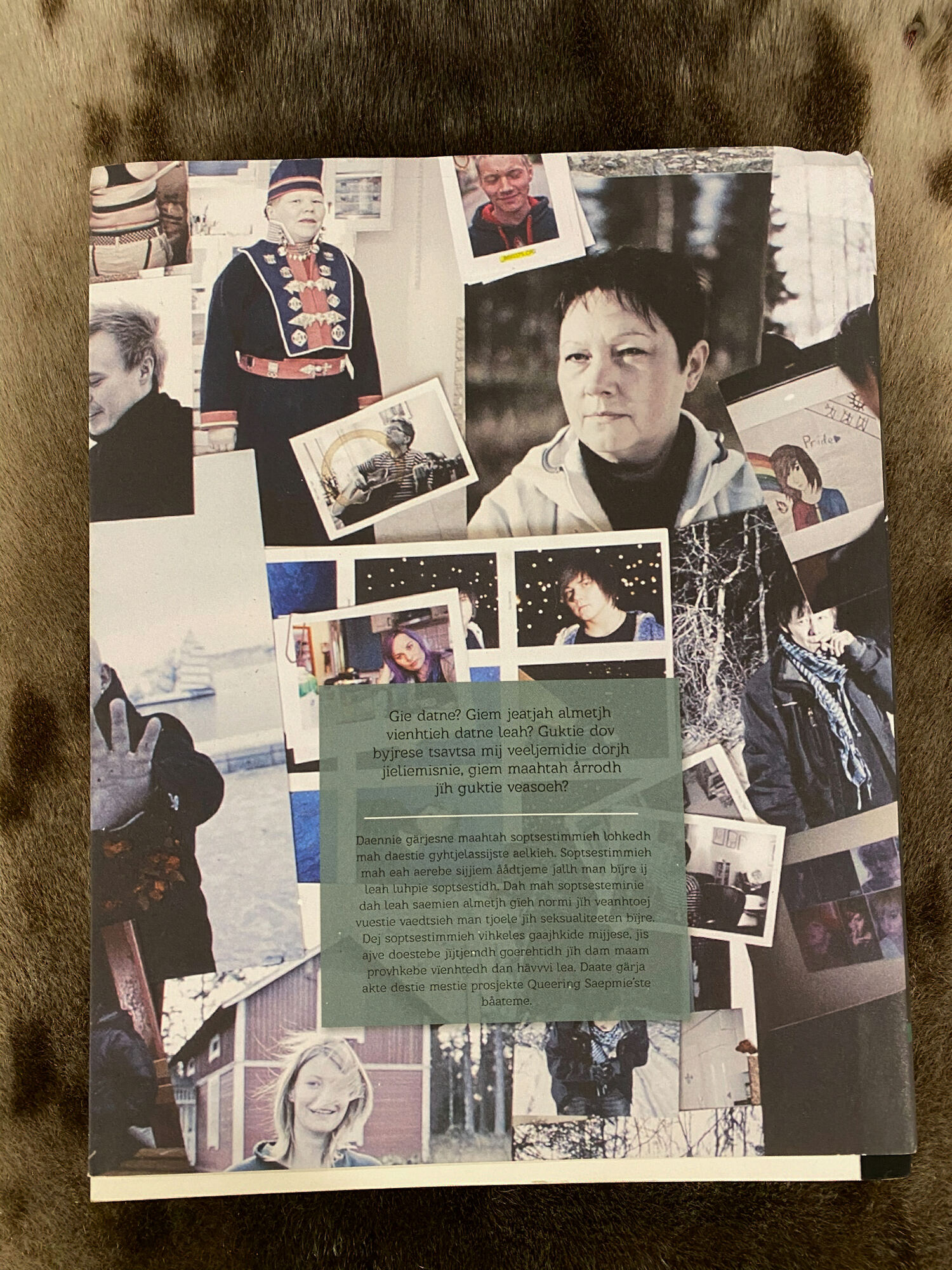

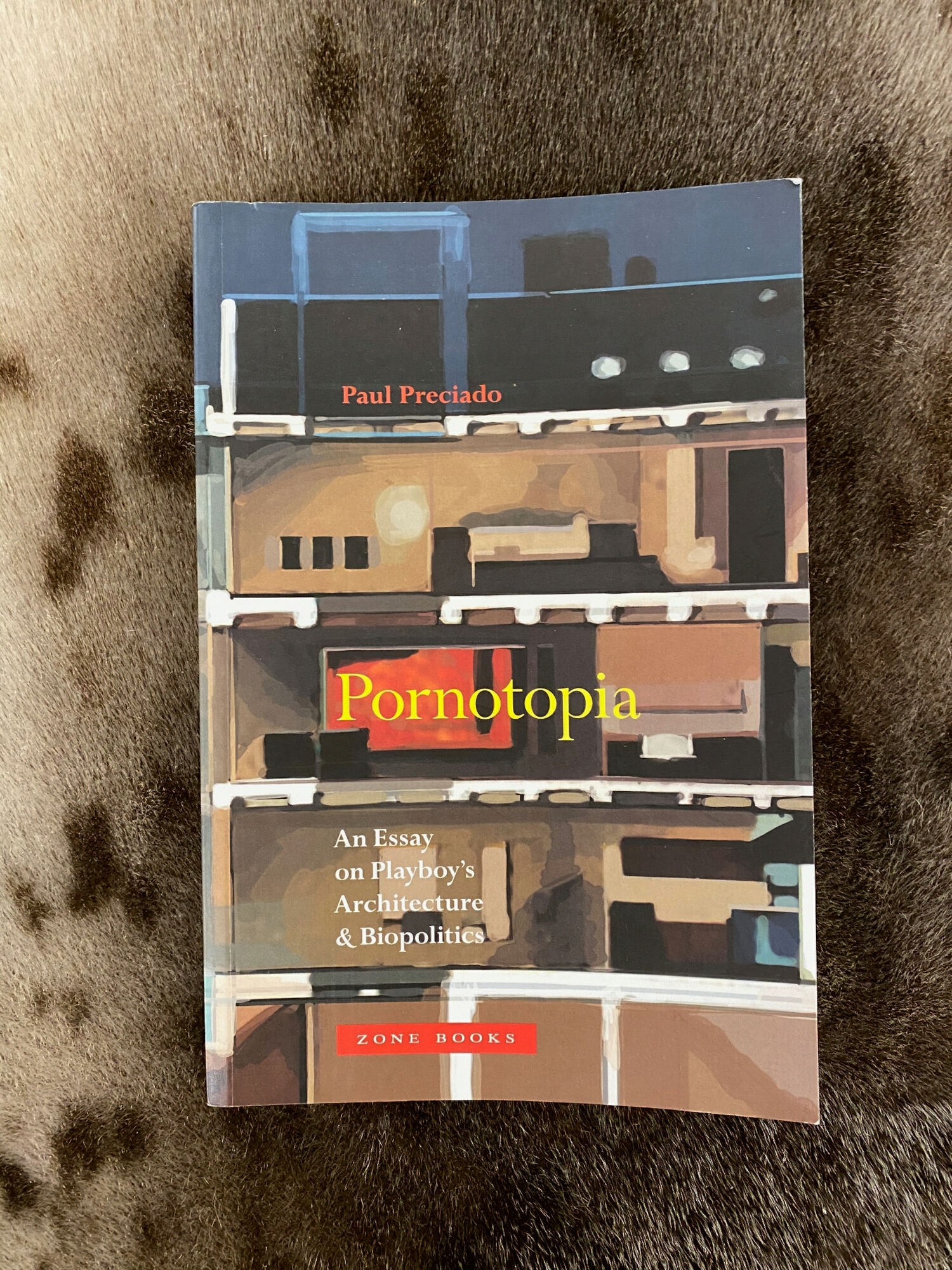

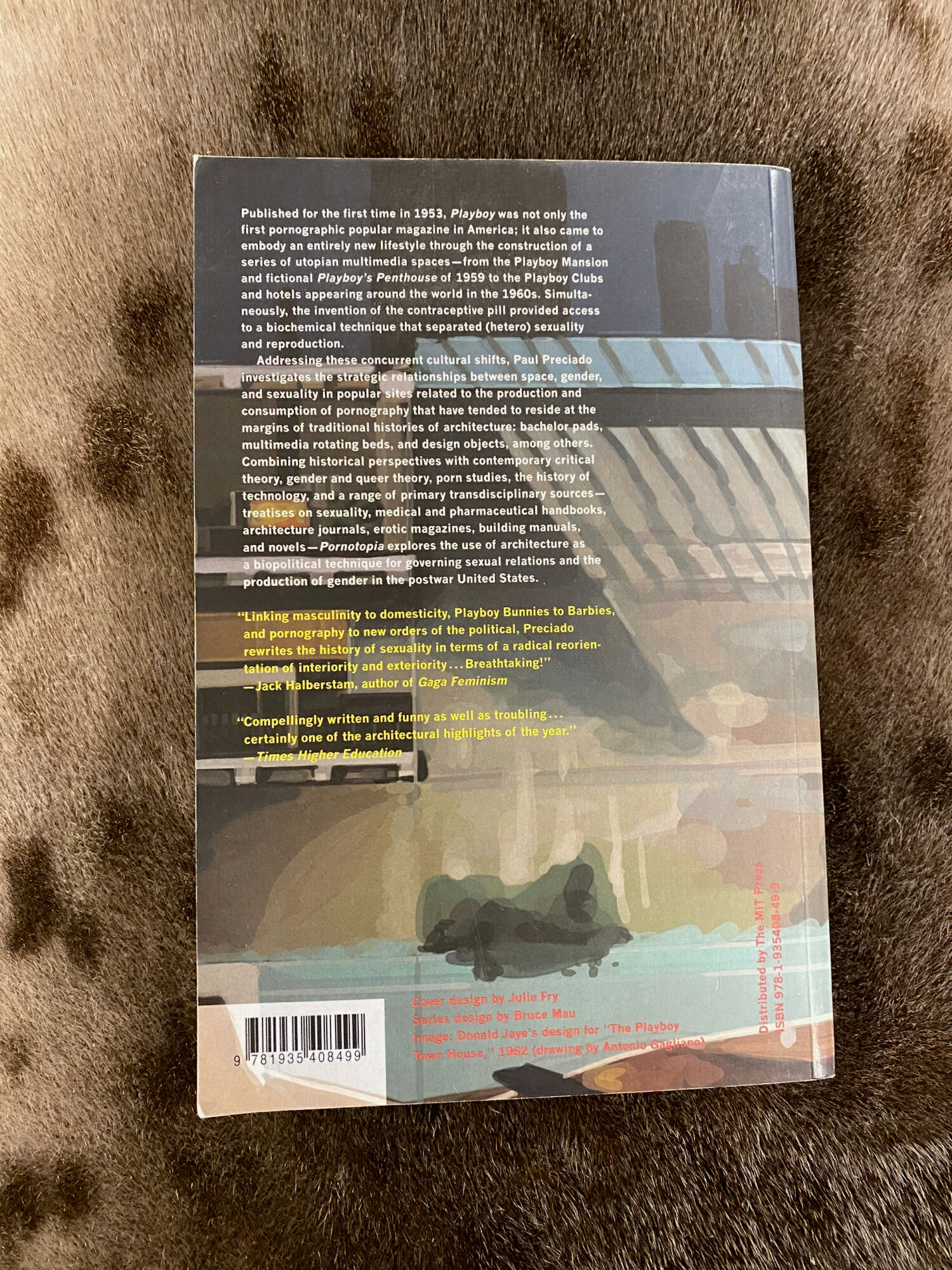

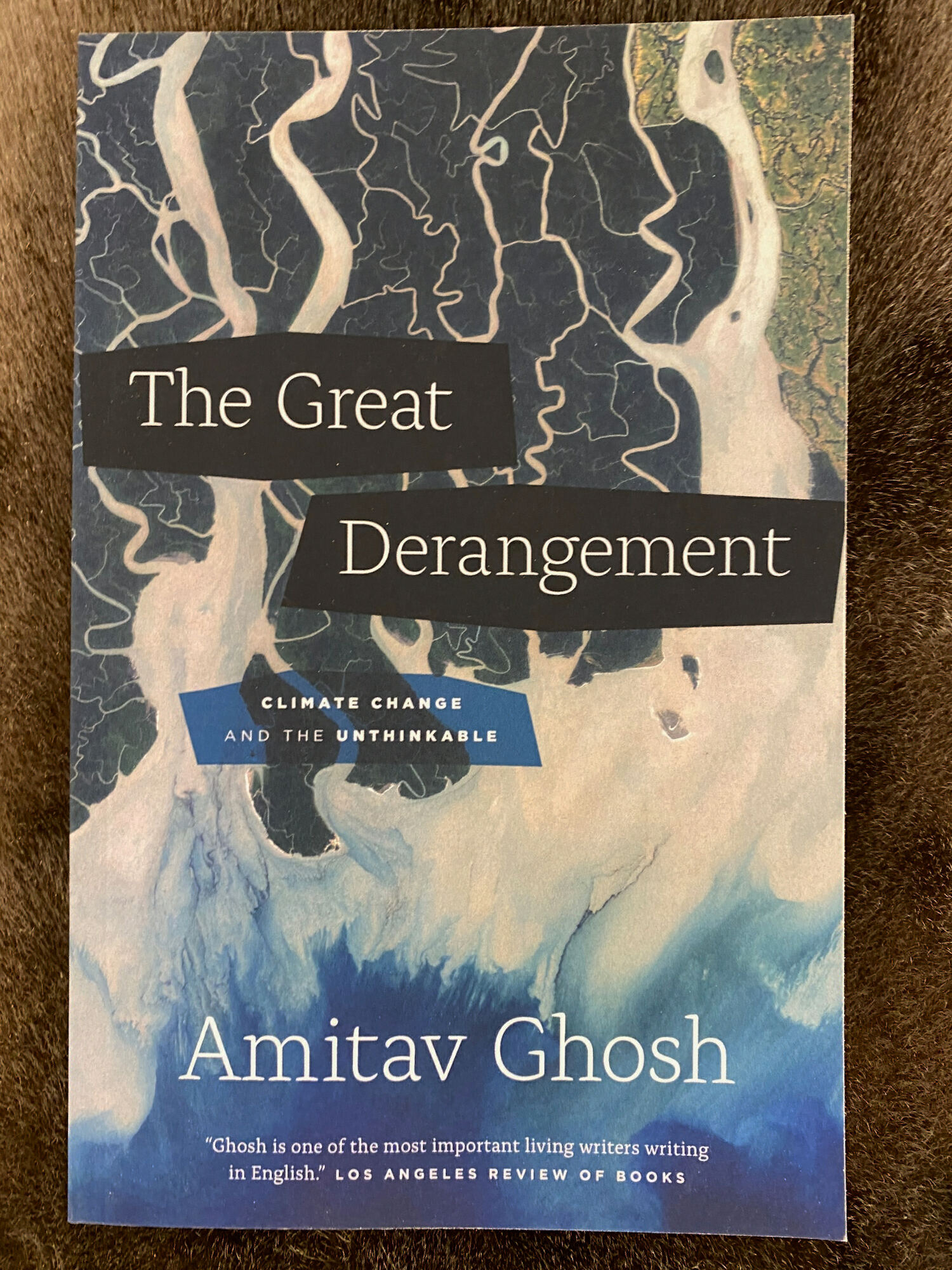

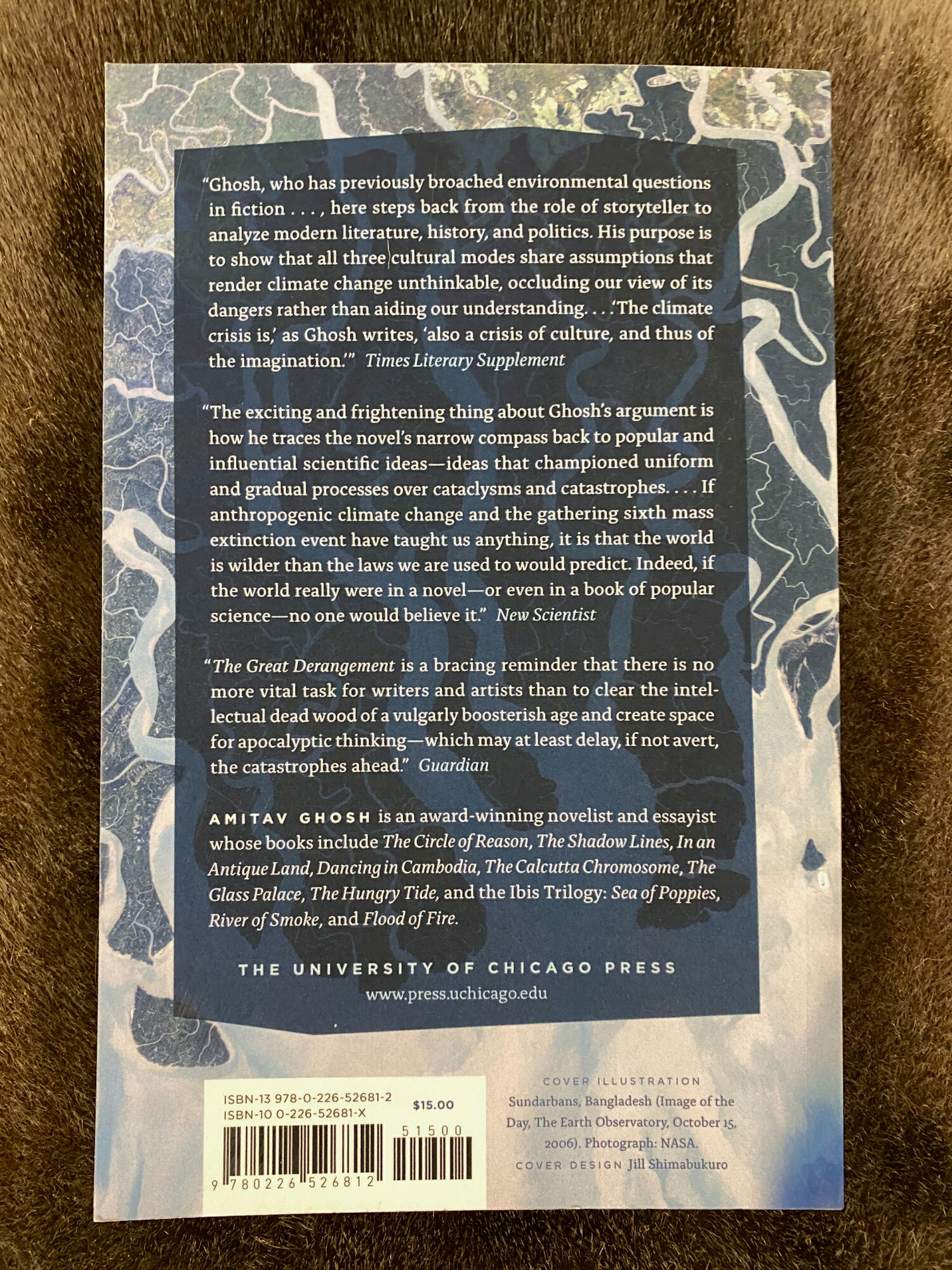

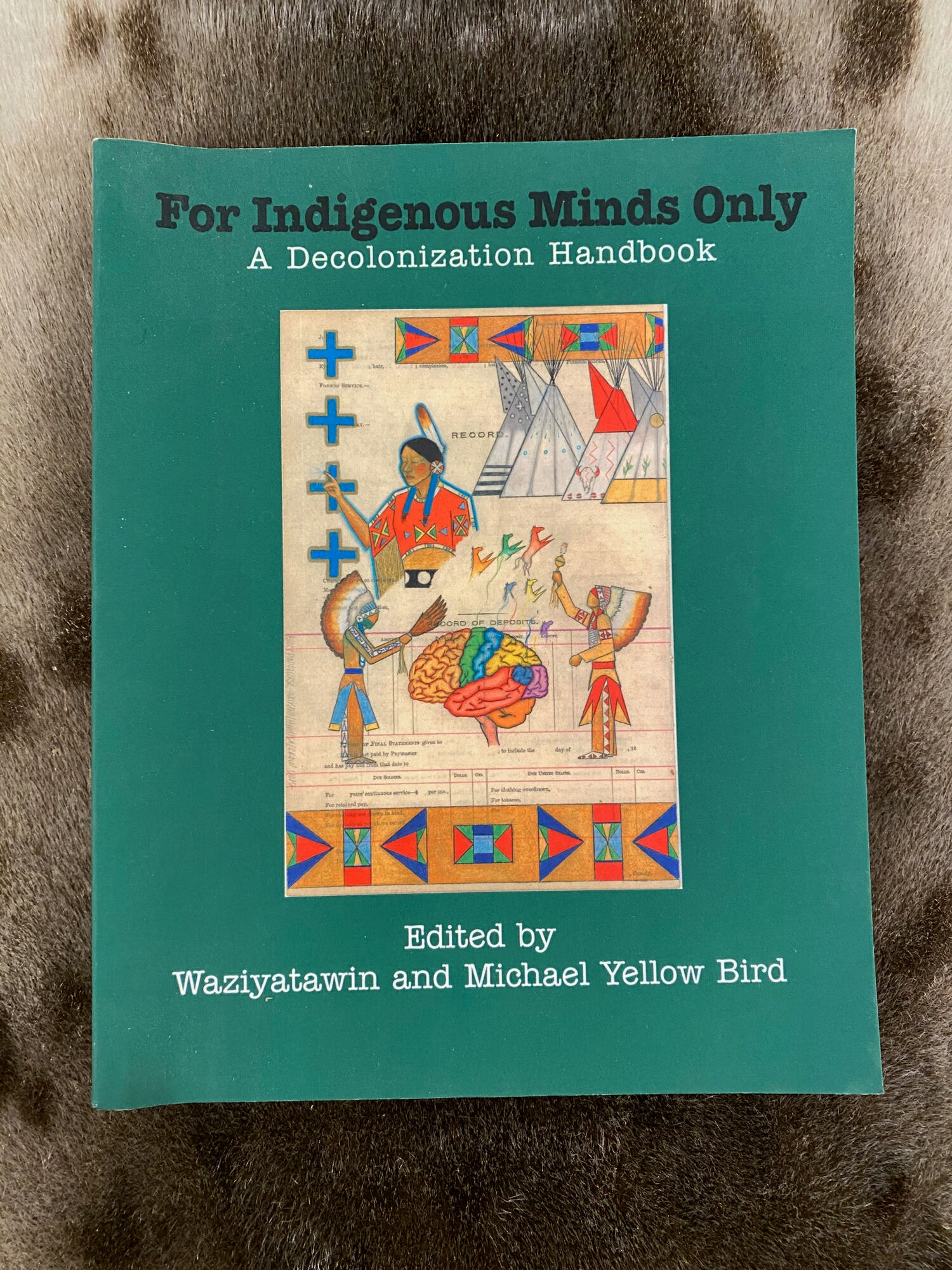

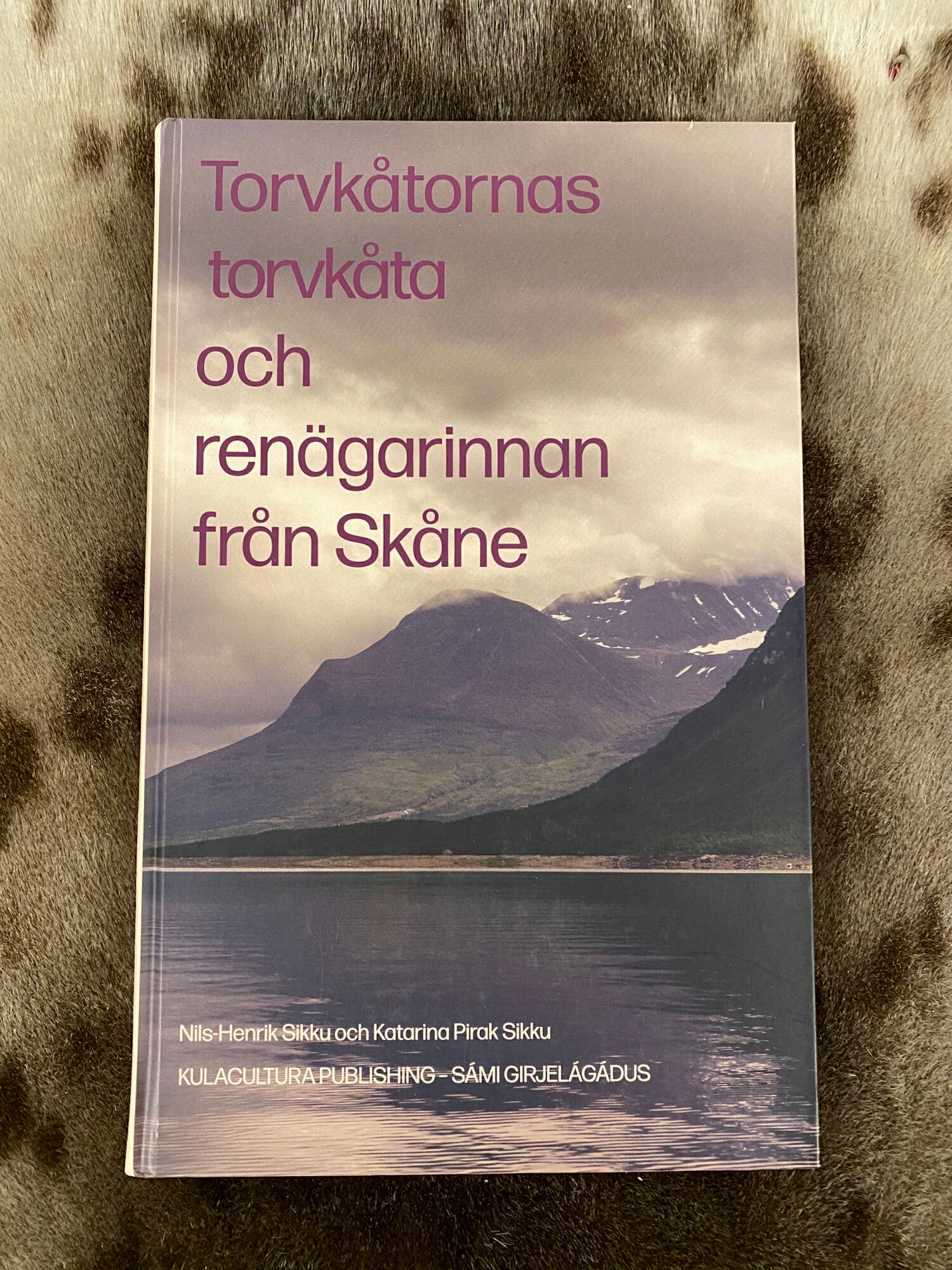

Welcome to the digital extension of Girjegumpi, a nomadic, collaborative library put together over the last fifteen years by architect and artist Joar Nango. The library’s archive comprises an expanding collection of more than 500 books embracing topics such as Sámi architecture and design, indigenous building knowledge, activism, and decoloniality. It includes artworks, films, tools, reused materials, and more. As an itinerant, collective library, the project has evolved and expanded as it has travelled to different locations, involving multiple collaborations.

"A big and related aspect to the flow of material is also the flow of people"

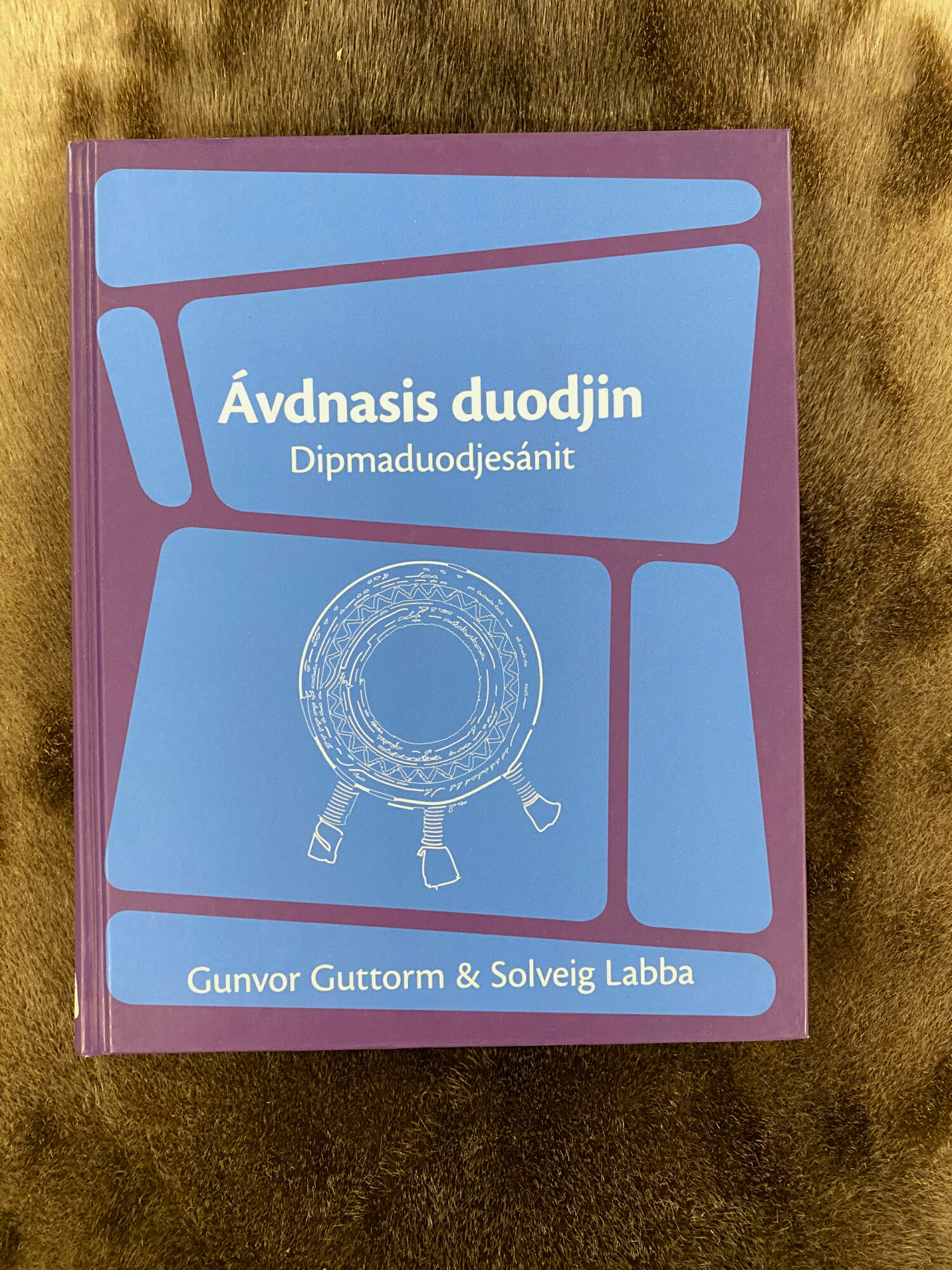

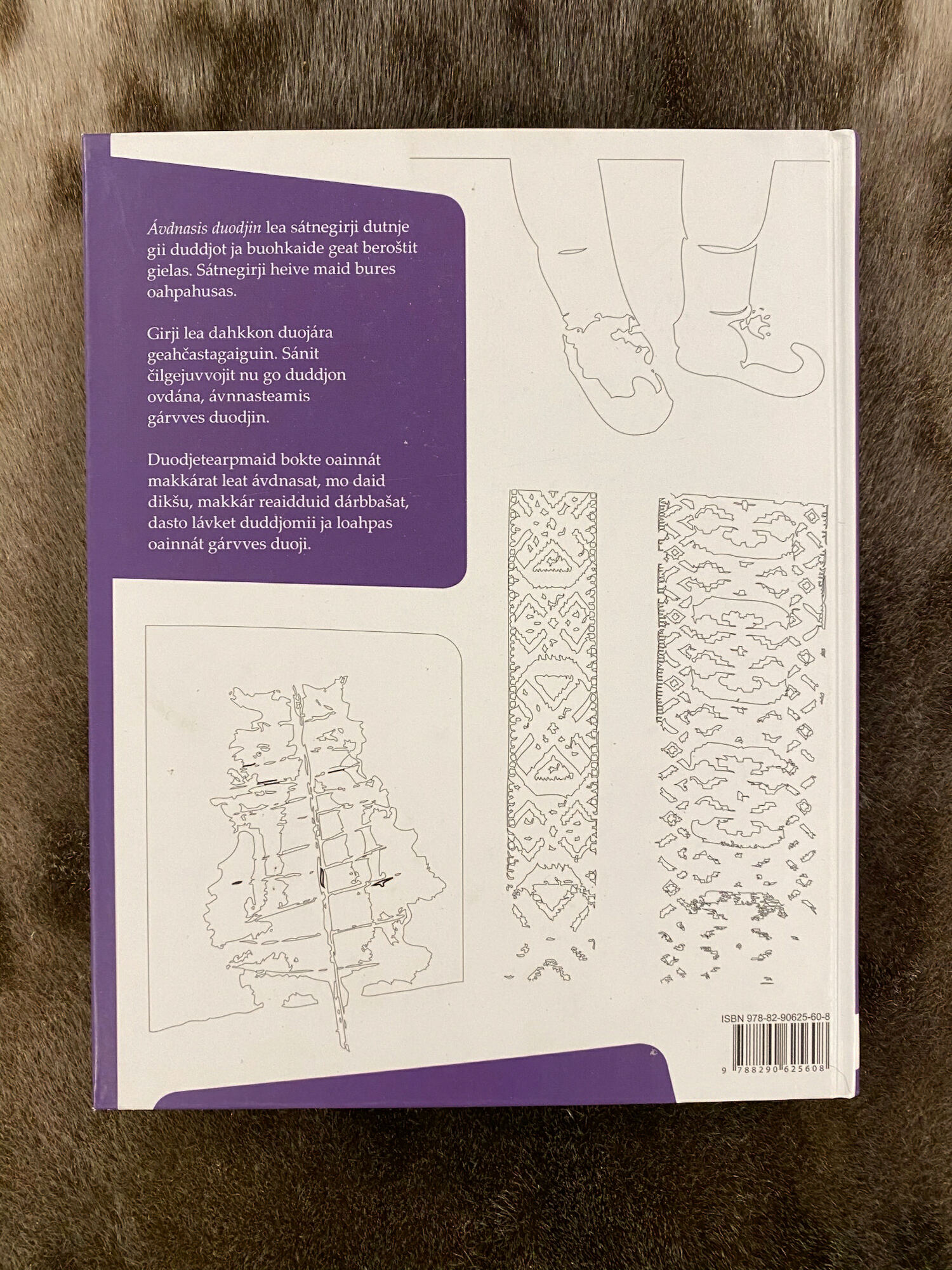

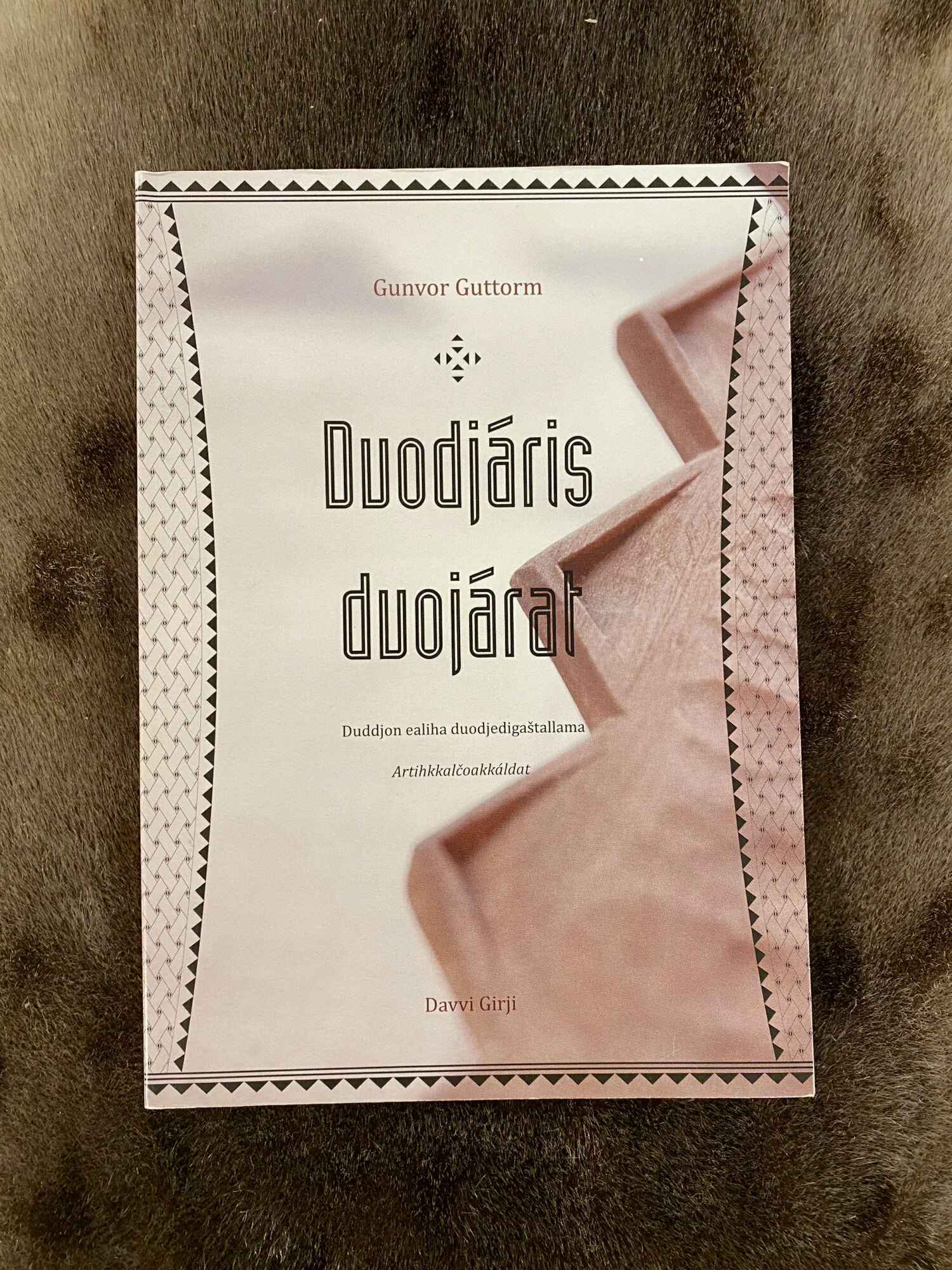

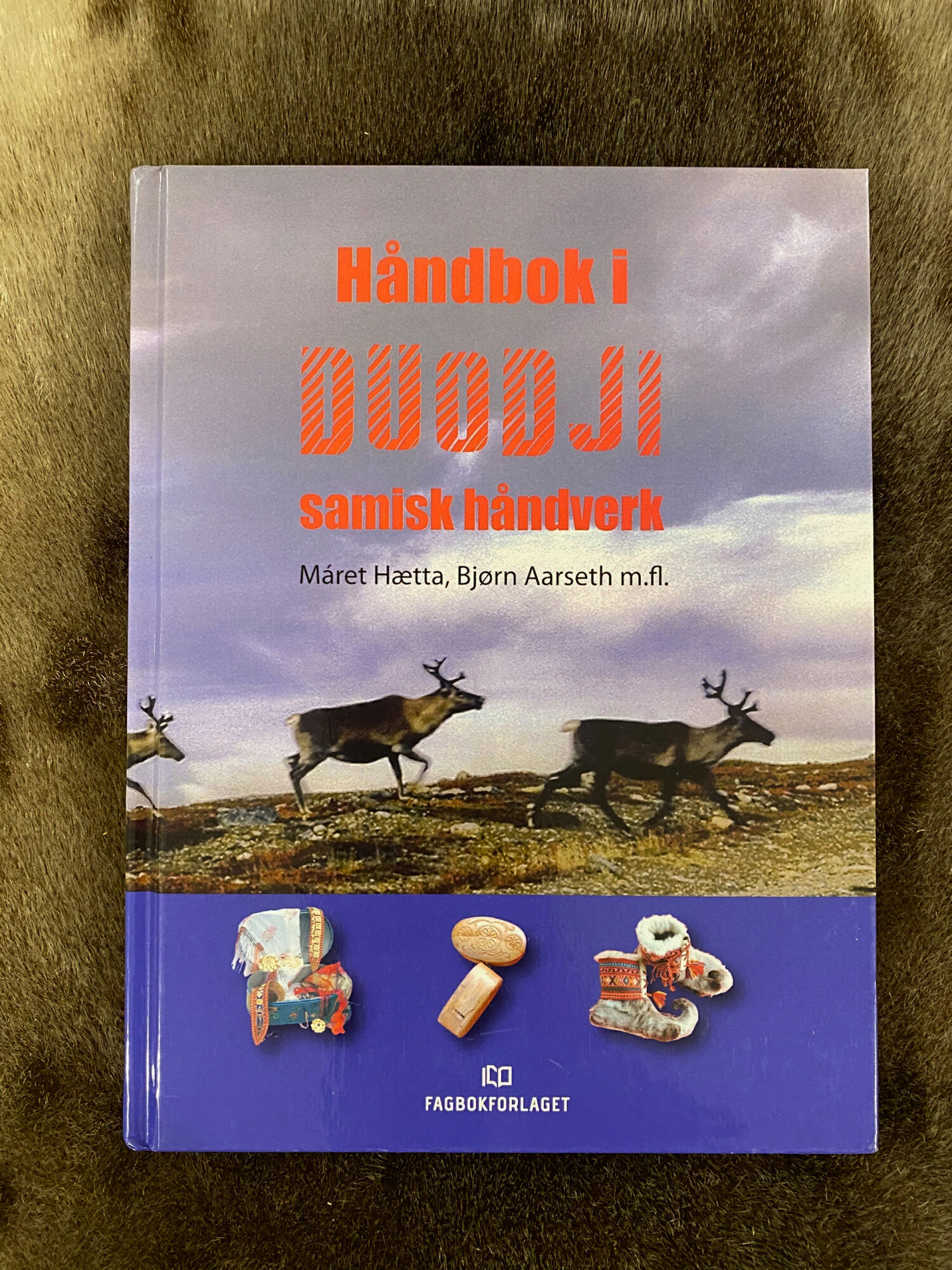

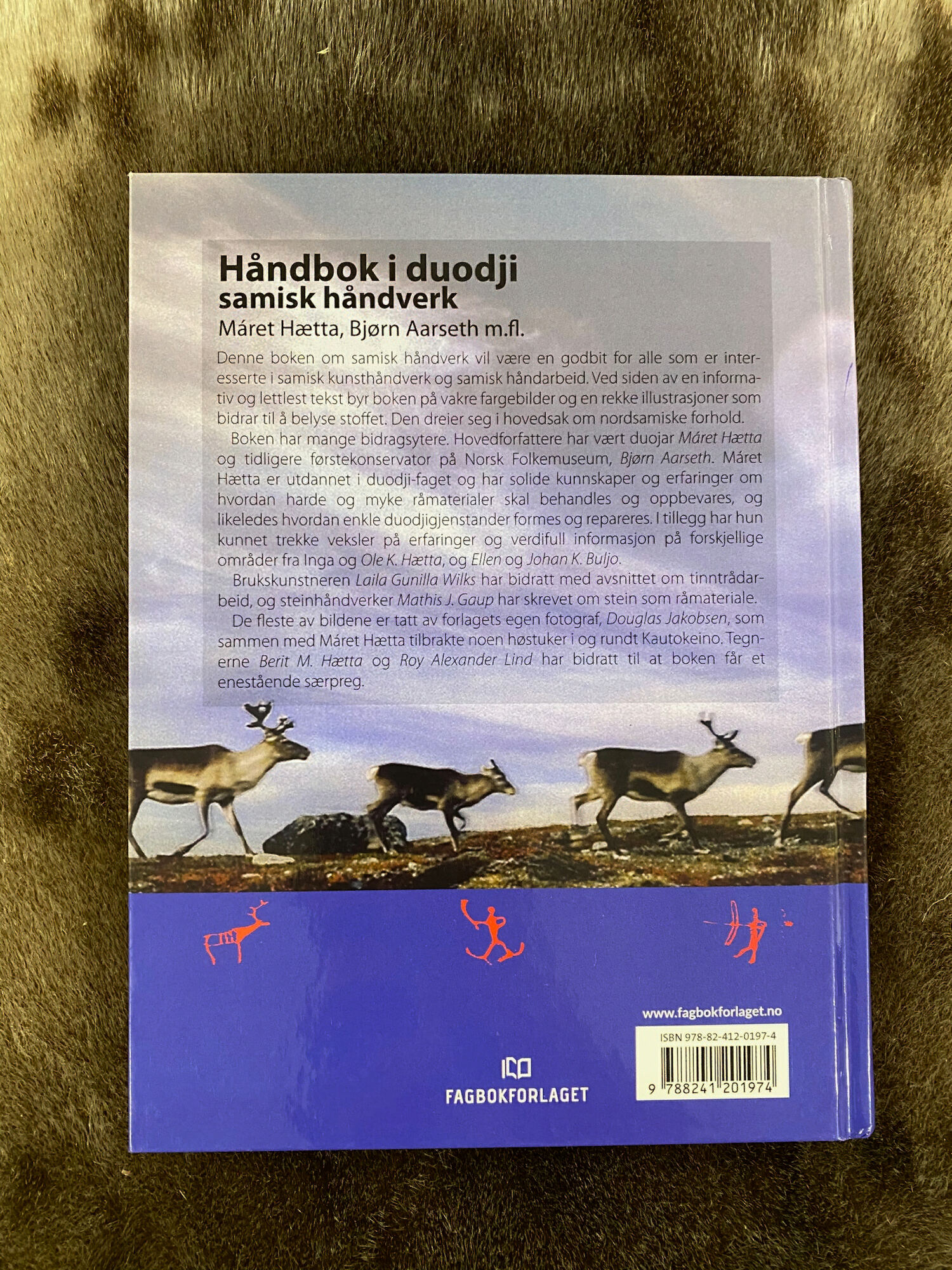

Namita Gupta Wiggers: Duodji as part of philosophy and cosmology, 21 Nov 2018

– Joar Nango

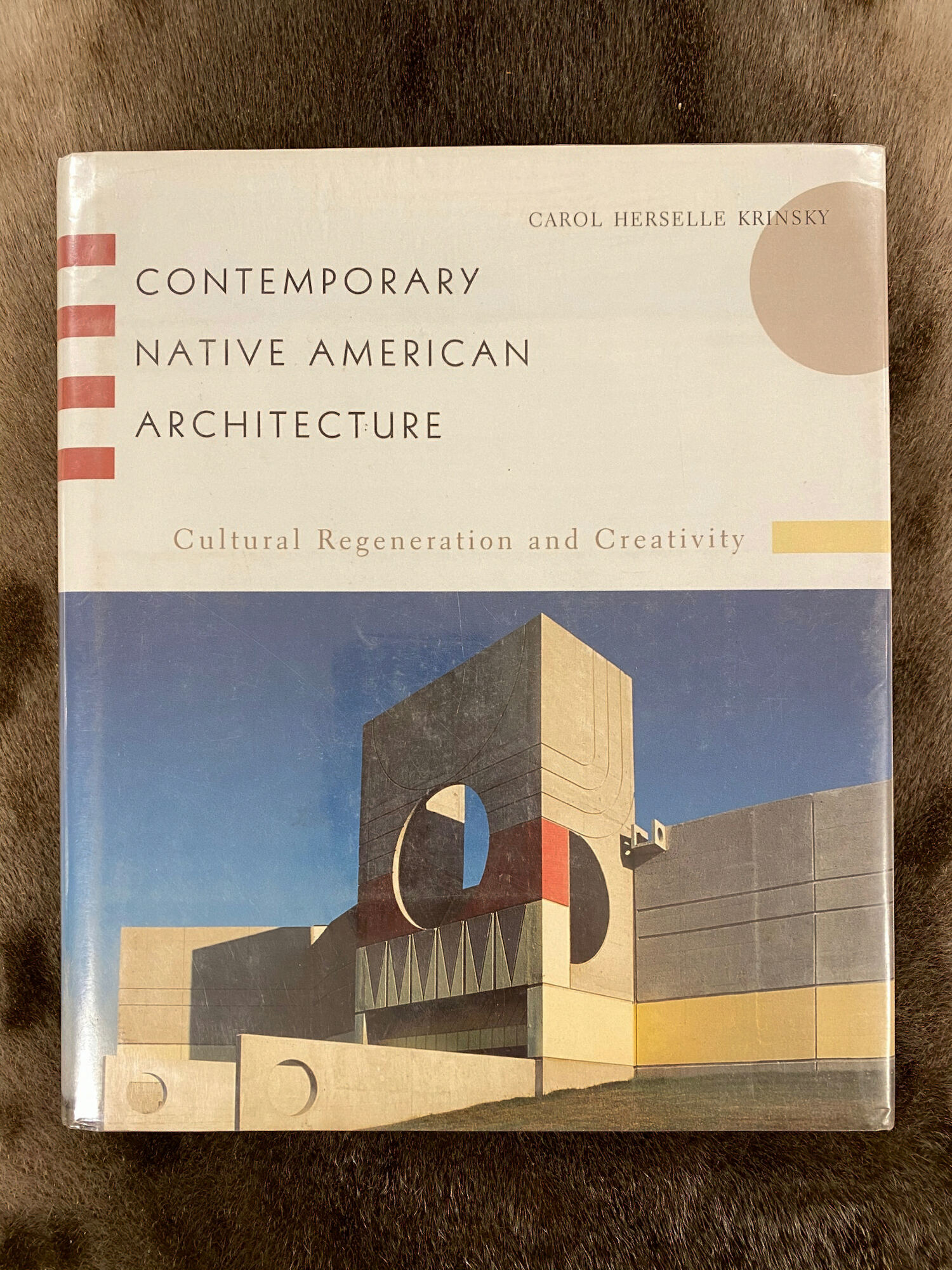

"Architecture to me is a form of art, inspired by forces of nature, respecting the environment and people that the architect is serving. I see architecture as art because I want it to uplift peoples’ spirits. When you walk into it you should feel a part of it and it should uplift your spirit, like all art does. Architecture should be enjoyed by people. It should be loved by people. That is the main purpose. The idea is to create a natural space. I also like to say that a building should be like a woman. In other words, it should be nurturing and protect people within. Architecture should be comforting, protecting, and caring everyone who enters the space."

Vladimir Belogolovsky: “A Building Should Be Nurturing and Protect People Within”: In conversation with Douglas Cardinal,

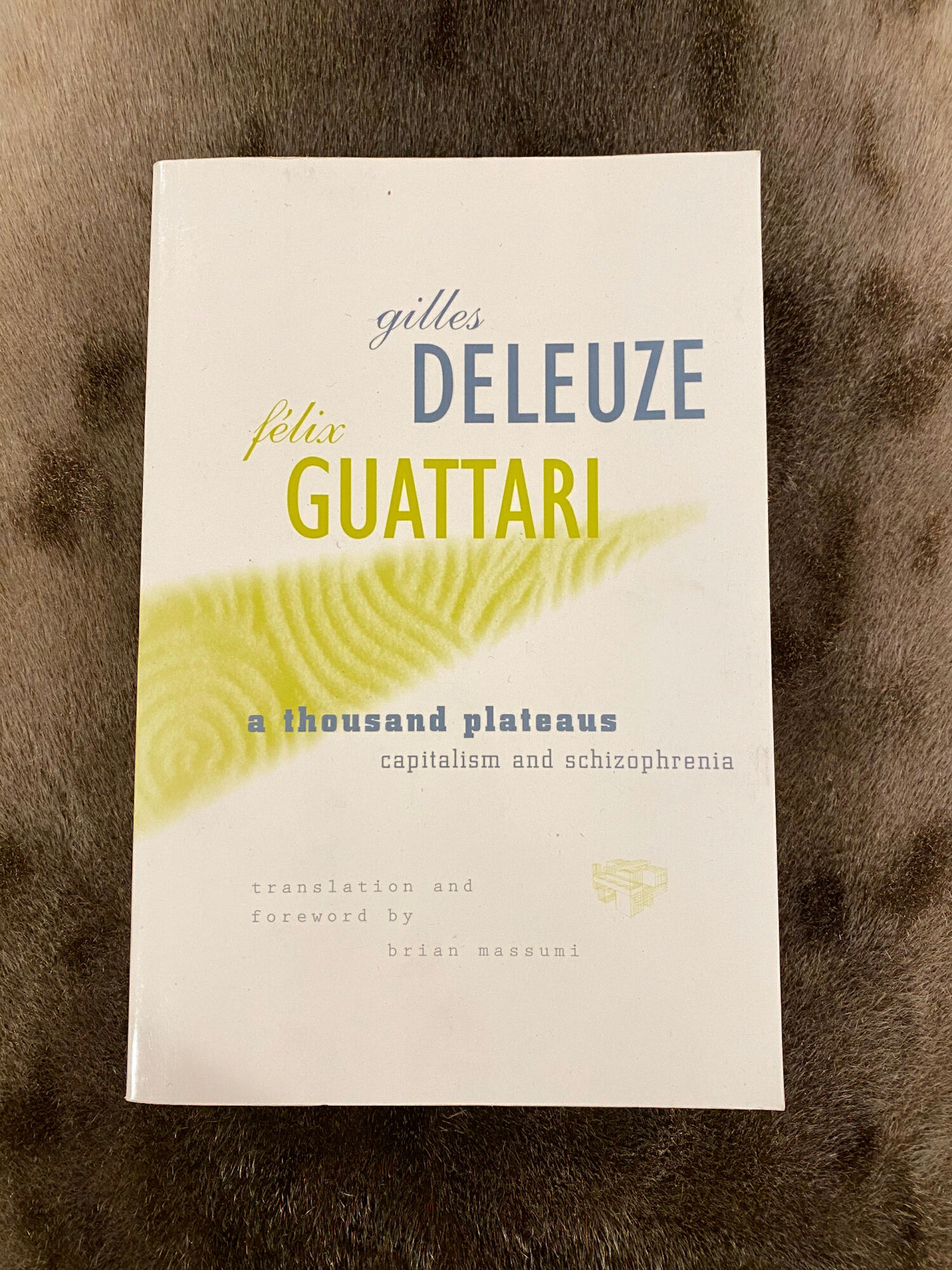

“The schizo knows how to leave: he has made departure into something as simple as being born or dying. But at the same time his journey is strangely stationary, in place. He does not speak of another world, he is not from another world: even when he is displacing himself in space, his is a journey in intensity, around the desiring-machine that is erected here and remains here. For here is the desert propagated by our world, and also the new earth, and the machine that hums, around which the schizos revolve, planets for a new sun. These men of desire - or do they not yet exist? - are like Zarathustra. They know incredible sufferings, vertigos, and sicknesses. They have their specters. They must reinvent each gesture. But such a man produces himself as a free man, irresponsible, solitary, and joyous, finally able to say and do something simple in his own name, without asking permission; a desire lacking nothing, a flux that overcomes barriers and codes, a name that no longer designates any ego whatever. He has simply ceased being afraid of becoming mad. He experiences and lives himself as the sublime sickness that will no longer affect him. Here, what is, what would a psychiatrist be worth?”

Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari: Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, 1972

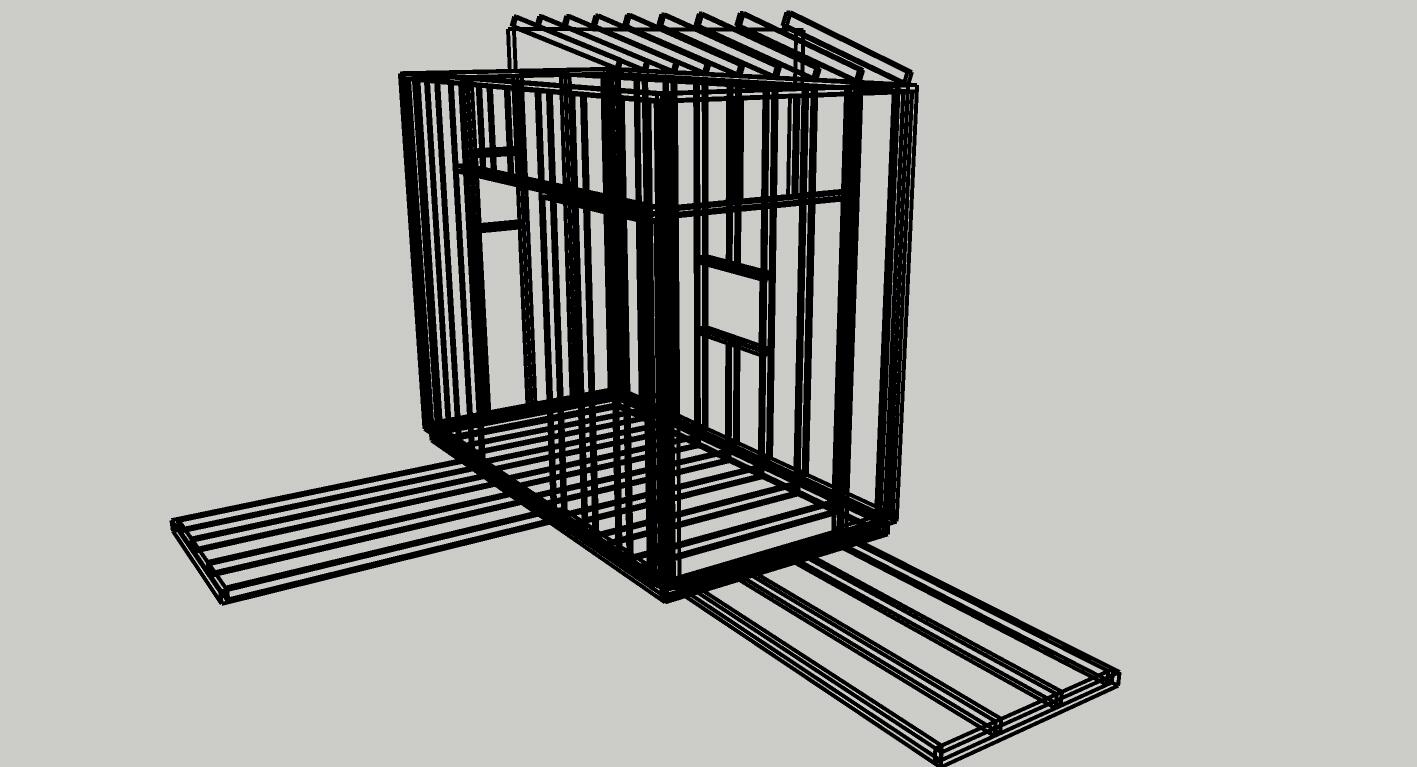

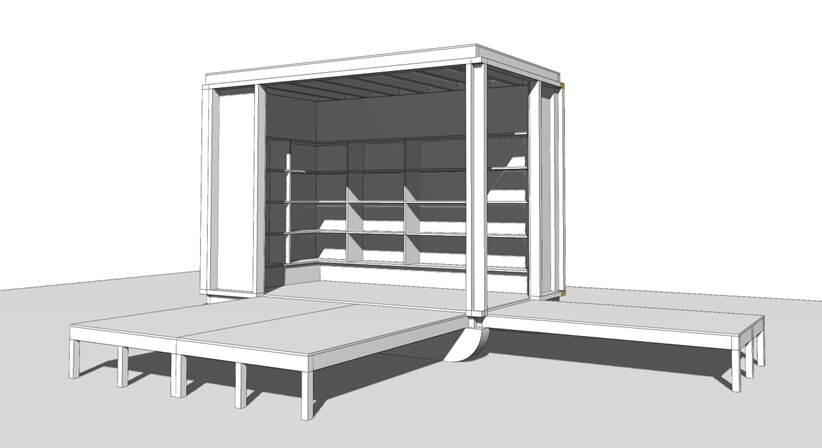

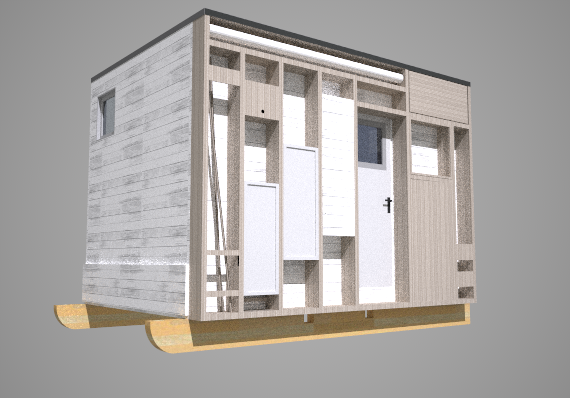

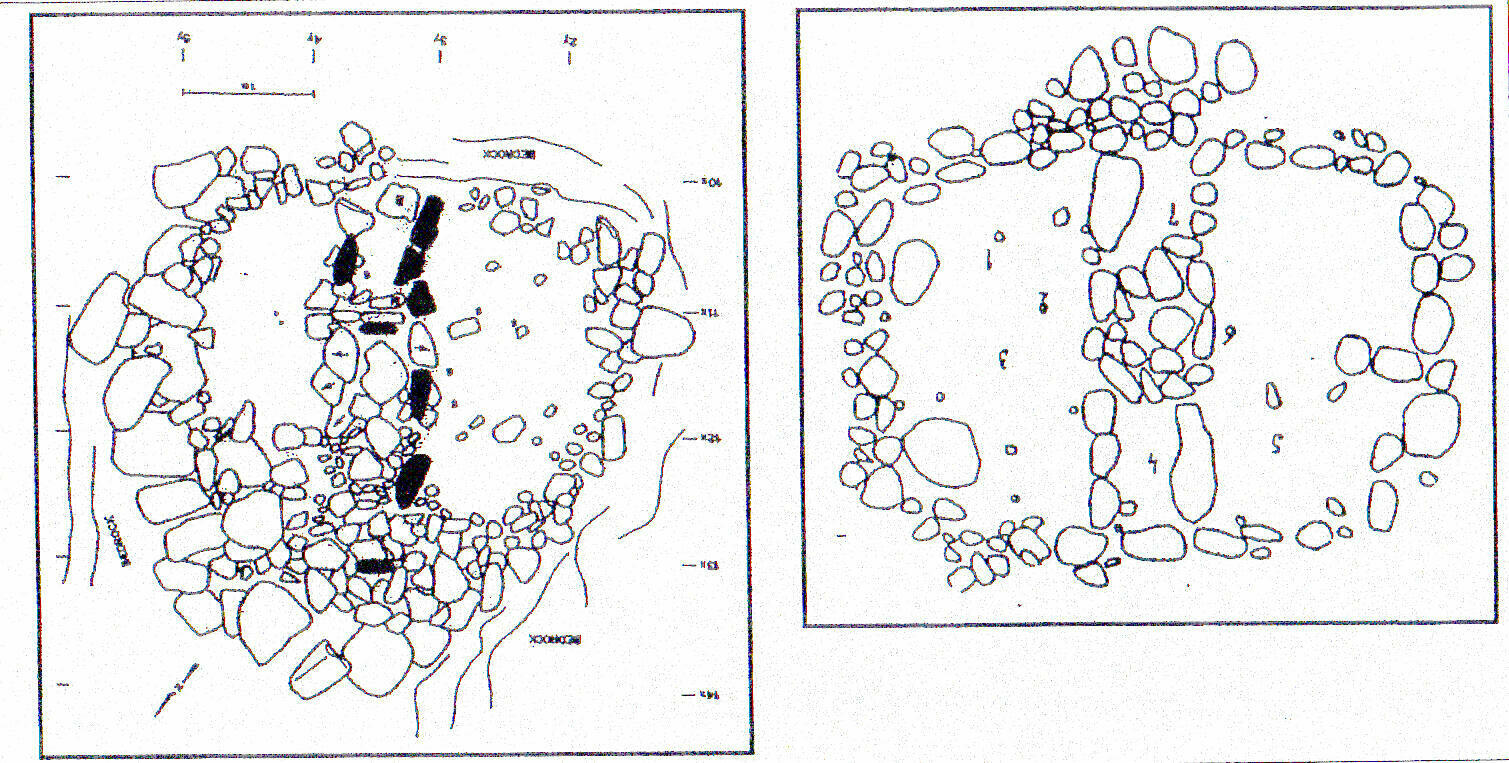

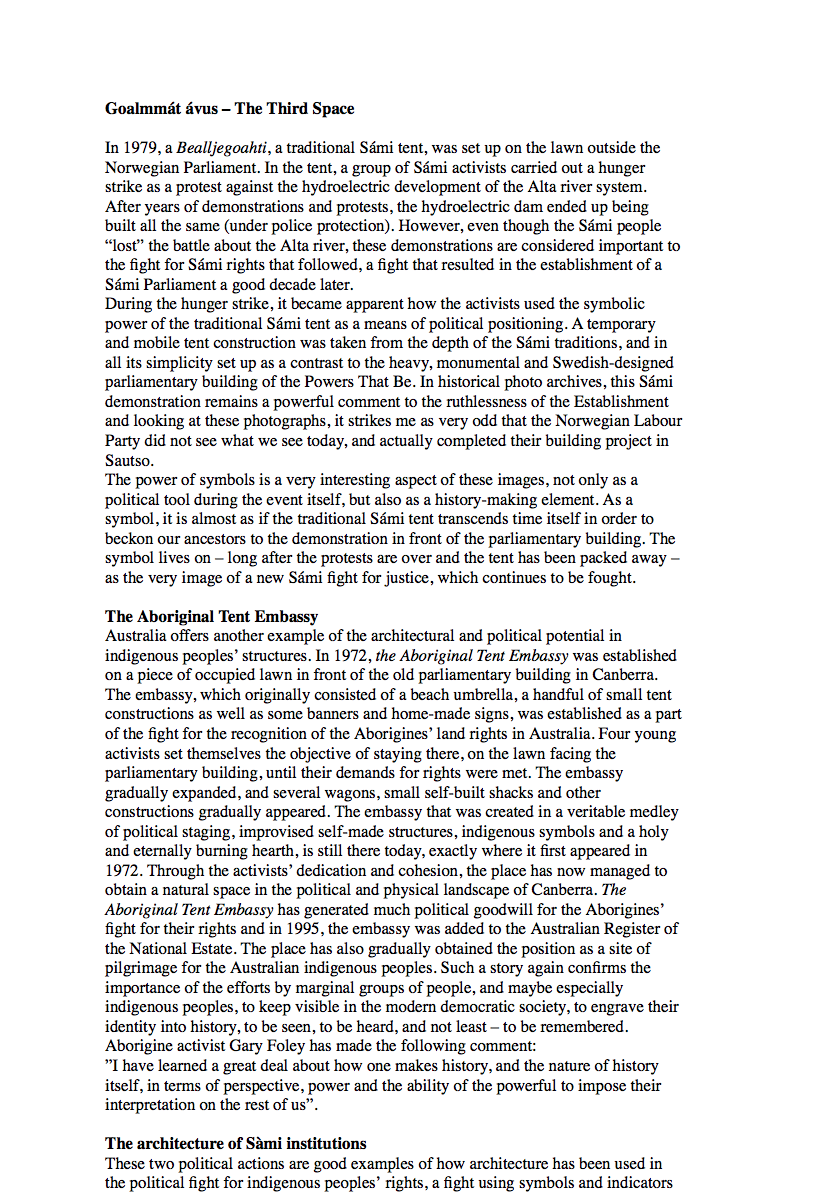

“The Sámi parliament, for example, is a semi circle; a half lavvu building. It’s interesting because it implies that we have a democracy, which we don’t. We have a parliamentarian system but it’s completely subservient to the Norwegian system. There are no autonomous decisions being made on behalf of the Sámi people there. So in one way, it has a representational quality to it, but really it’s a way of distracting us to make us believe that we are succeeding more than we are. It makes me think about creating a new parliament building where we could really rethink our political systems. For example, The Sámi are a people who live across four nation states. How great would it be if we created a political system that included the people on all sides of the borders? And if you created a parliament around that constellation. This parliament could be moveable, and could be made up of four huge trailer trucks that would drive around. Each truck could park side by side and pull this huge tent structure between them. The back doors would open up, creating this gigantic caravan tent; a space for negotiation. And based on that concept, the way you negotiate would change, would develop. There’s a sense of hierarchy in architecture that can become very static, and this would serve to counter that issue.”

A conversation between Joar Nango and Rebecca Lemire: Architectural Potential and Indigeneity, OCTOBER 15 – DECEMBER 3, 2016

"We often hear people arguing that we Sámi are already multicultural, that multiculturalism is not an issue we think about, as multicultural encounters are part and parcel of our everyday lives. To some extent, being part of the Sámi community renders this true, as the cultural background enables one to manage in the environment into which one has been born. However, Sámi society also needs to enhance its capacity to examine and understand culture from a more reflective perspective in order to note prejudices, stereotypes, variations, changes, similarities and differences. Sápmiis a term for the area where Sámi people live and also signifies their imagined community. Sámi are an indigenous people who reside within the present-day borders of Norway, Finland, Sweden and Russia. In Sápmi, in the broader sense, authorities and people need to be enabled to treat people justly and impartially."

Asta Mitkija Balto & Liv Østmo, Saami University College: Multicultural studies from a Sámi perspective: Bridging traditions and challenges in an indigenous setting, January 2012

”På 1950- og 60-tallet kaltes det assimilering og fornorsking. I dag kalles det integrering. Ideen om at et felleskap, et samfunn, er avhengig av kulturell enighet, er likevel den samme. Men kaskje trenger vi heller et dissensfellesskap, sier Joar Nango. Fellesskapsprosjektet for å Fortette Byen (FFB) laget et midlertidig forsamlingshus for norske romfolk på Tullinløkka i Oslo.”

Joar Nango, Arkitektur N 5, The Norwegian Review of Architechture: Boligutvikling i Byen: Den Norske Romamassade, 2012

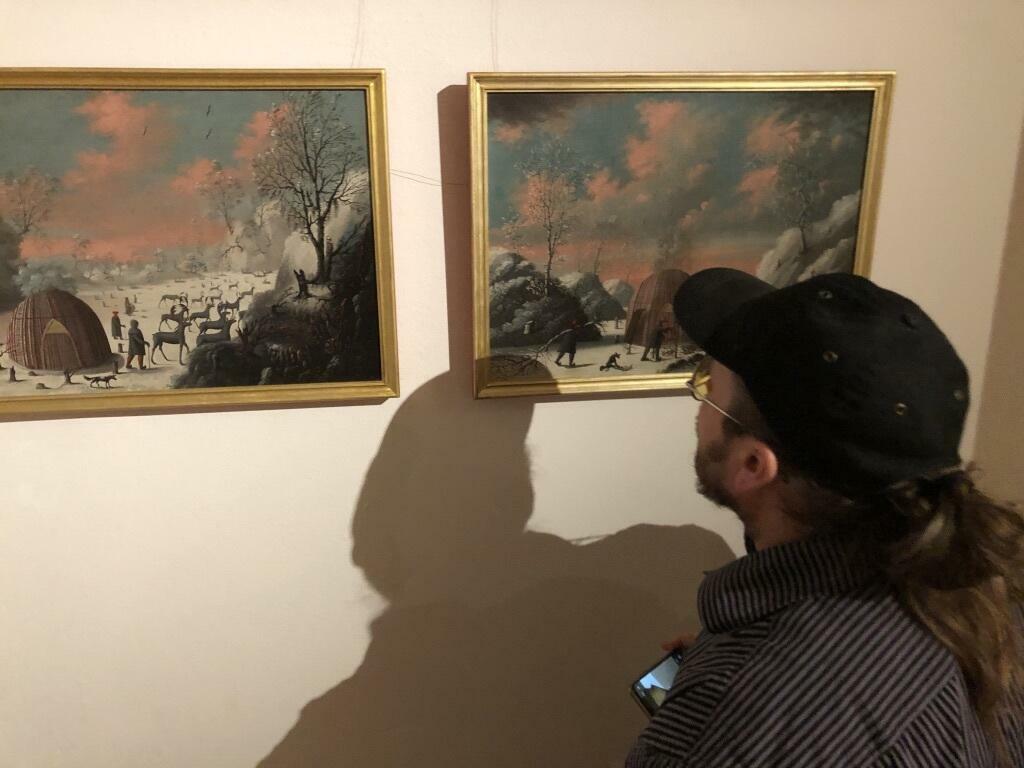

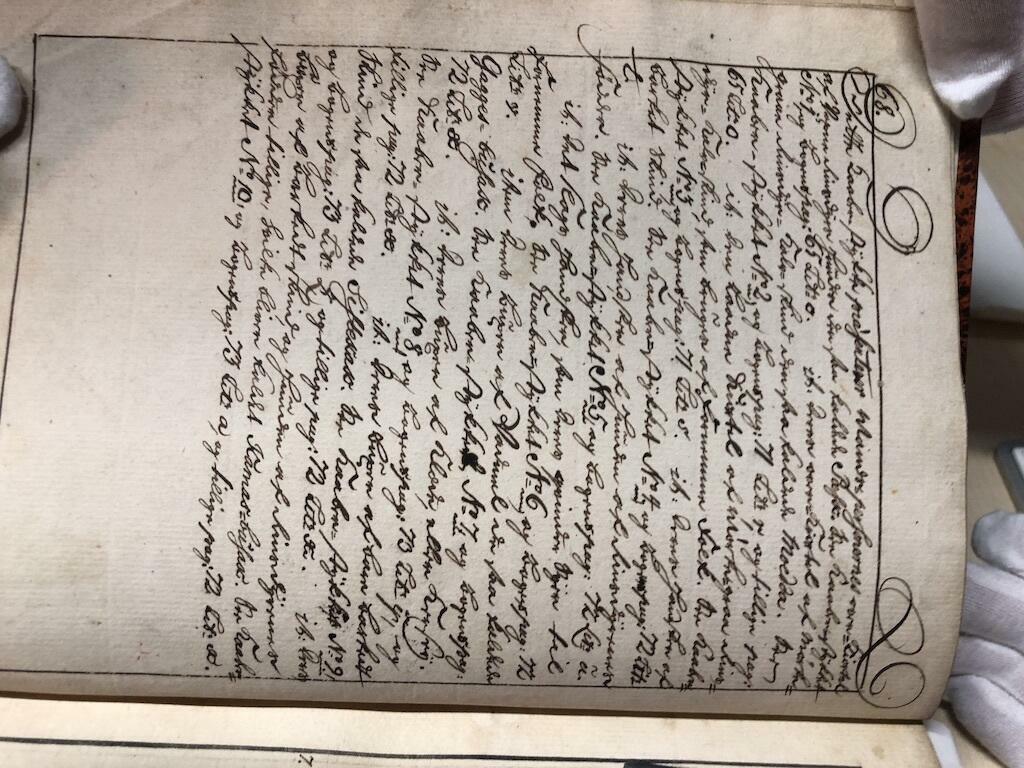

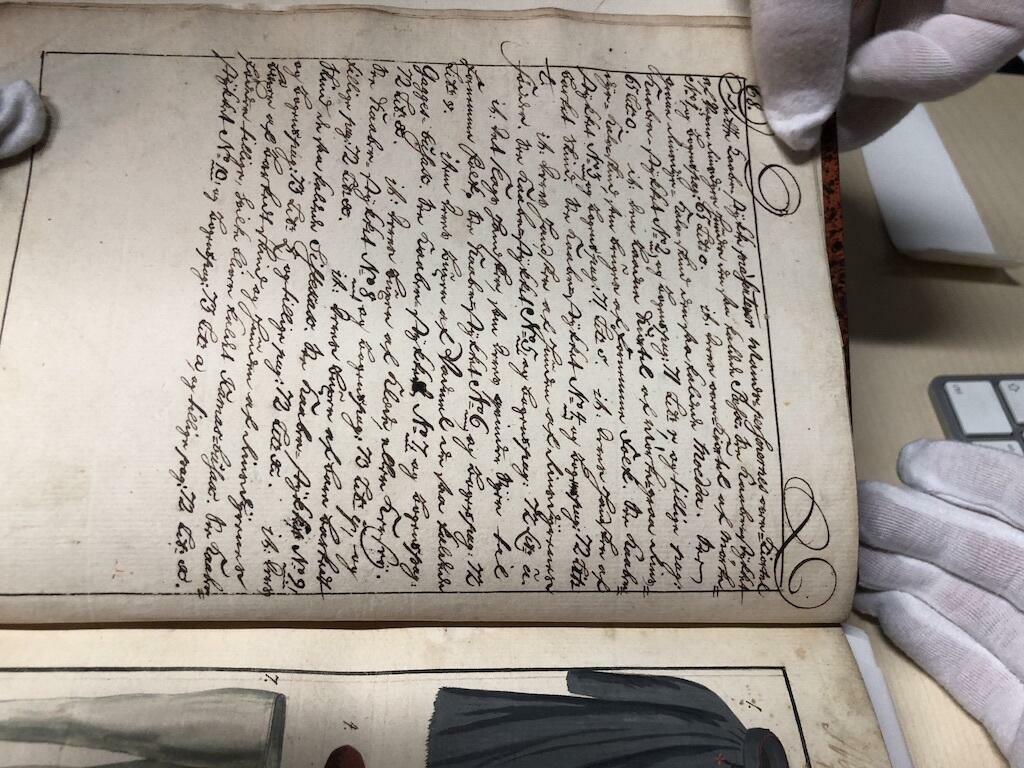

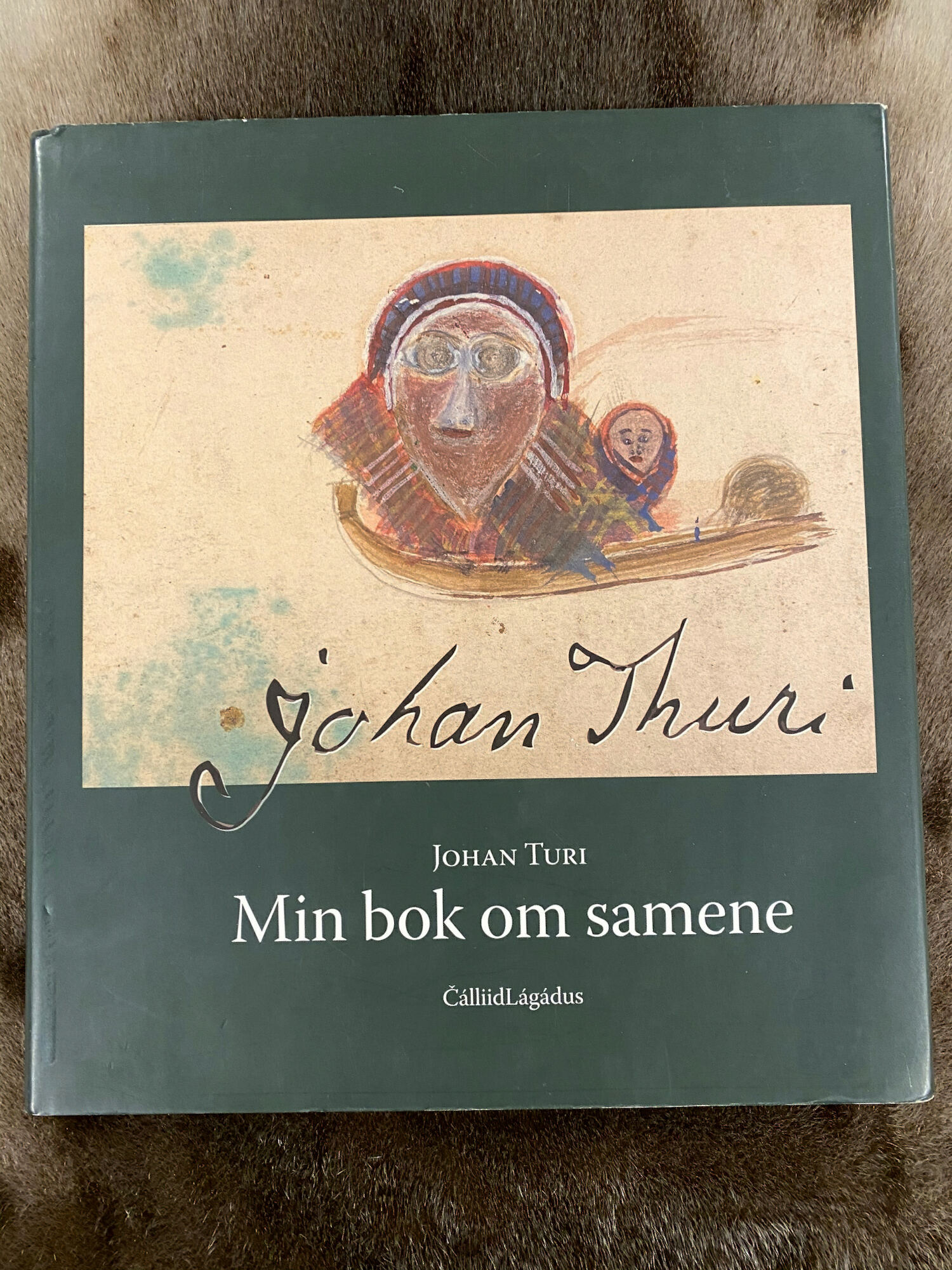

"On my visiting trips in Nordland and Finmark I have often noticed that especially the Finns in Finnmark, both the Mountain Finns and Sea Finns, do not want to be called Lapps […], although they are undeniably one People together with the Russian Lapps and the Swedish Lapps. Yes, I even read the same about the Swedish Lapps in Schefferus’ Lapponia, so it was not surprising

that they did not like this name: Lapps, which according to Schefferus’ is an offending word that others have put on them. […] Every Finn I have asked to name his people in his own language has replied that it is: Sabmeladzh; in plural Same. In Lappish or Finnish it is Samas. They call their language Same-gieel and their country Same-ednam."Manuscript copy of an essay written for a publication that will be published in connection

Mathias Danbolt: Control, Collect, Copy – article part of ”The Art of Nordic Colonialism: Writing Transcultural Art Histories”, 2020

with Joar Nango’s exhibition, fall 2020.

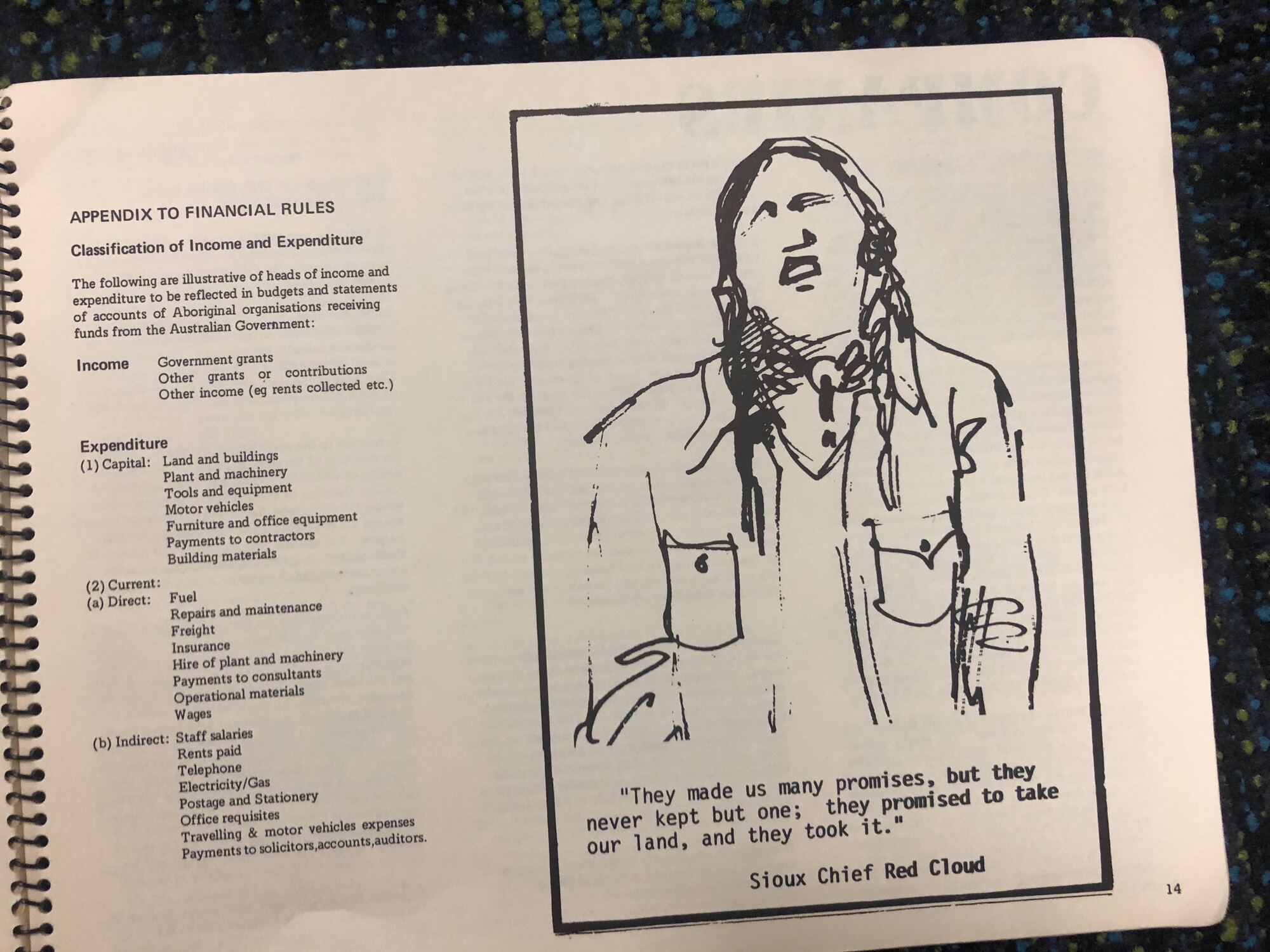

"Let us admit it, the settler knows perfectly well that no phraseology can be a substitute for reality.”

Eve Tuck State University of New York at New Paltz K. Wayne Yang University of California, San Diego: Decolonization is Not a Metaphor, 2020-02-01 00:00:00

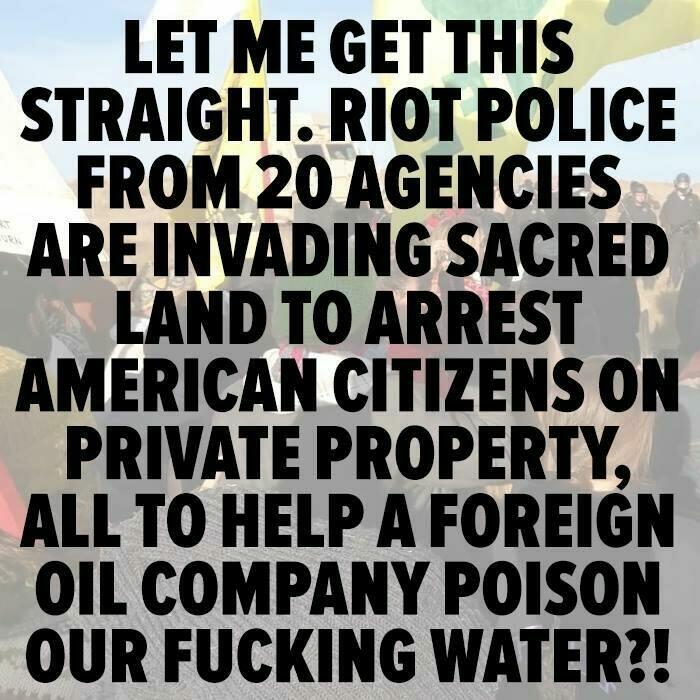

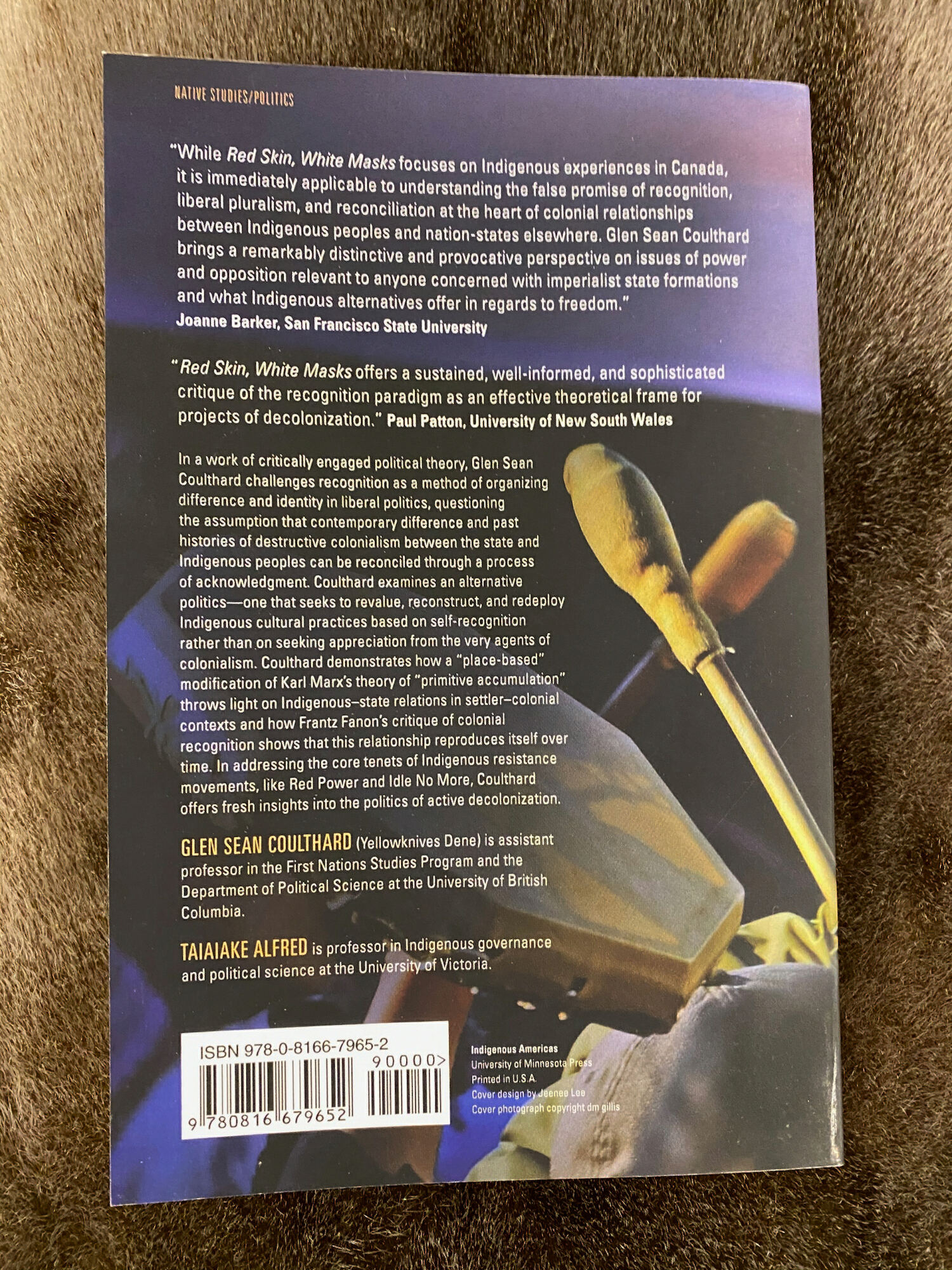

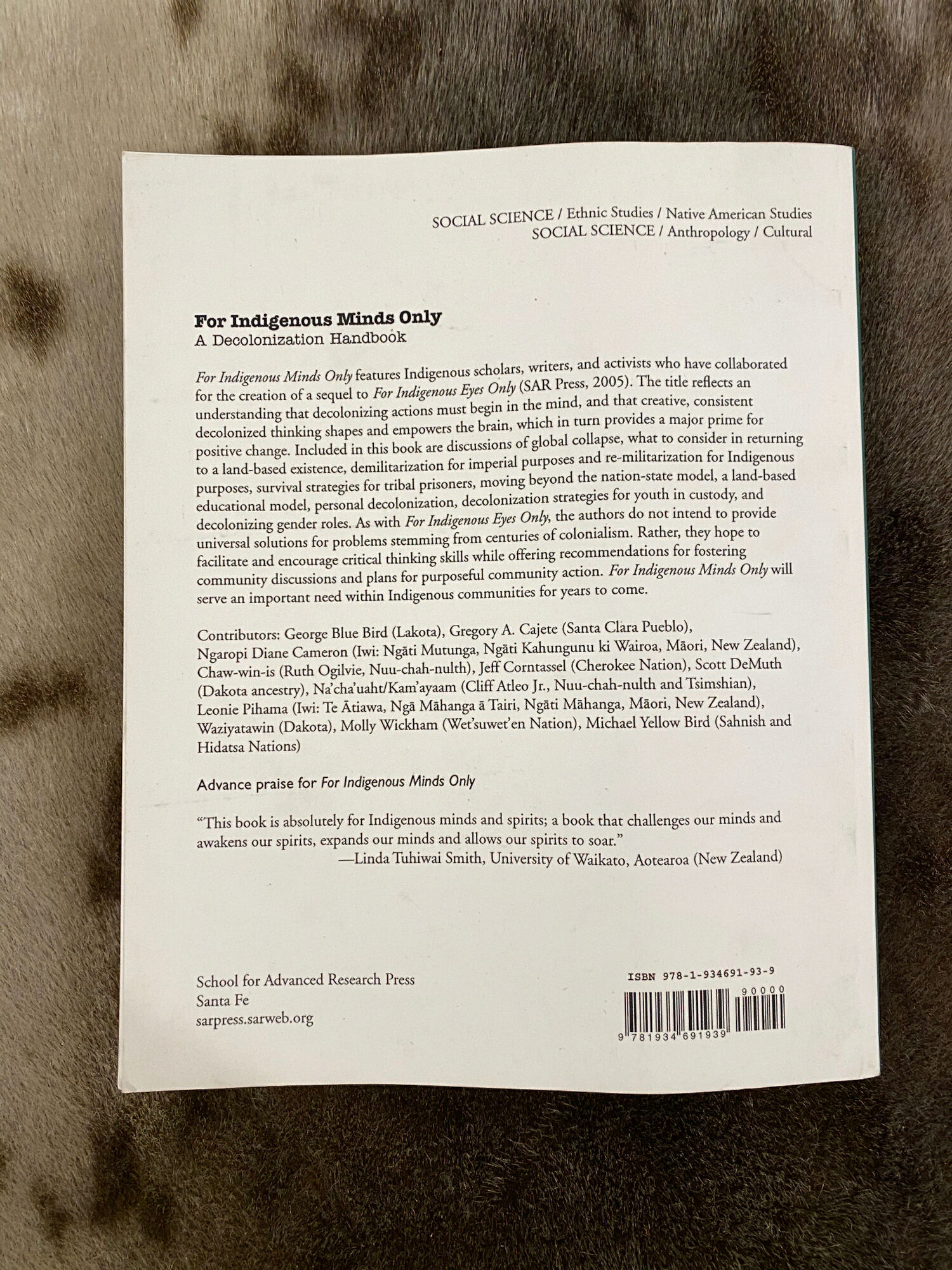

“At a conference on educational research, it is not uncommon to hear speakers refer, almost casually, to the need to “decolonize our schools,” or use “decolonizing methods,” or “decolonize student thinking.” Yet, we have observed a startling number of these discussions make no mention of Indigenous peoples, our/their struggles for the recognition of our/their sovereignty, or the contributions of Indigenous intellectuals and activists to theories and frameworks of decolonization.”

Eve Tuck State University of New York at New Paltz K. Wayne Yang University of California, San Diego: Decolonization is Not a Metaphor, 2012

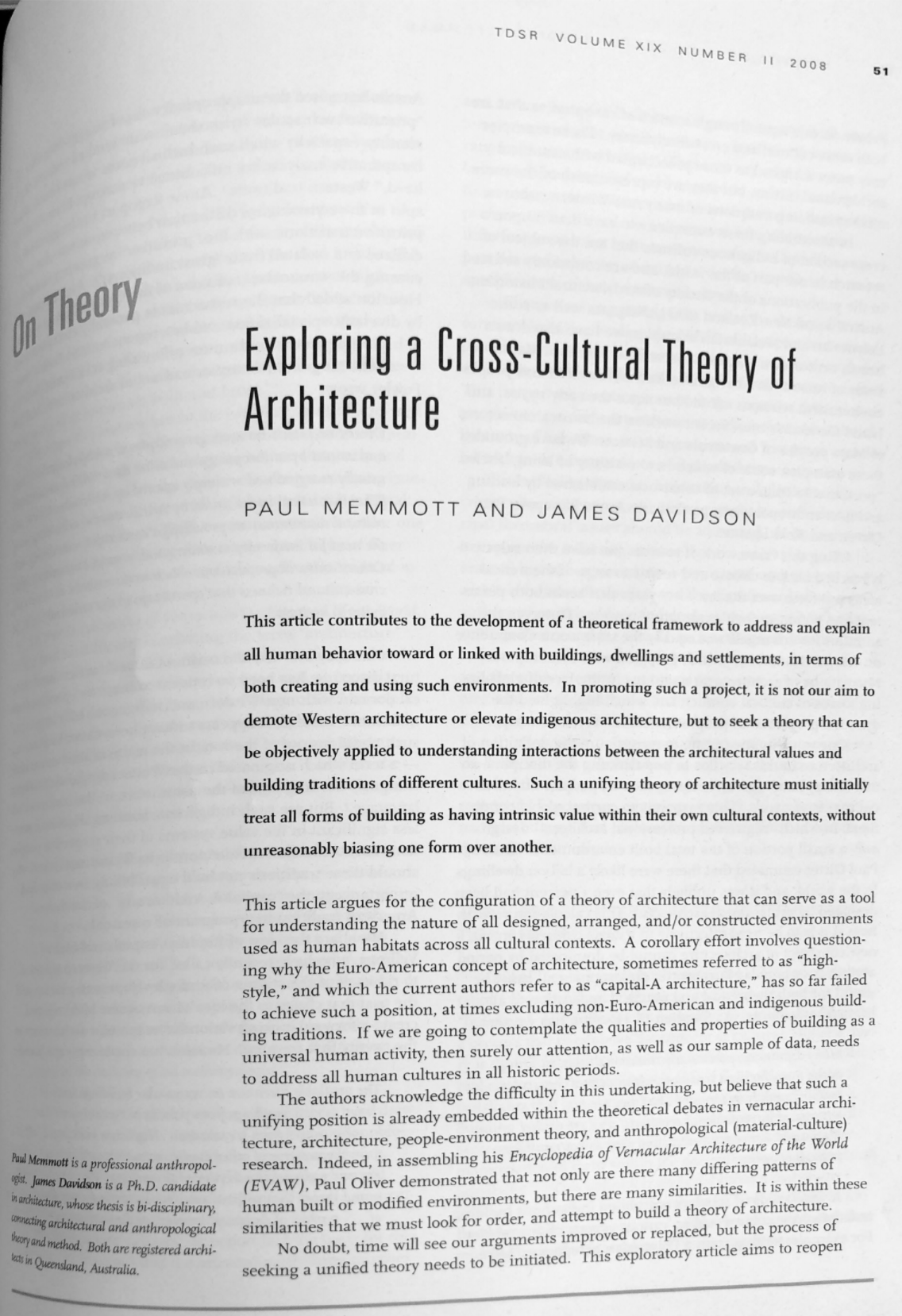

Folding Forced Utopias, For You

Joar Nango: , 2016

“Writing has nothing to do with meaning. It has to do with landsurveying and cartography, including the mapping of countries yet to come.” “Bring something incomprehensible into the world!” “It is not the slumber of reason that engenders monsters, but vigilant and insomniac rationality.”

Gilles Deleuze & Felix Guattari: Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, 1972

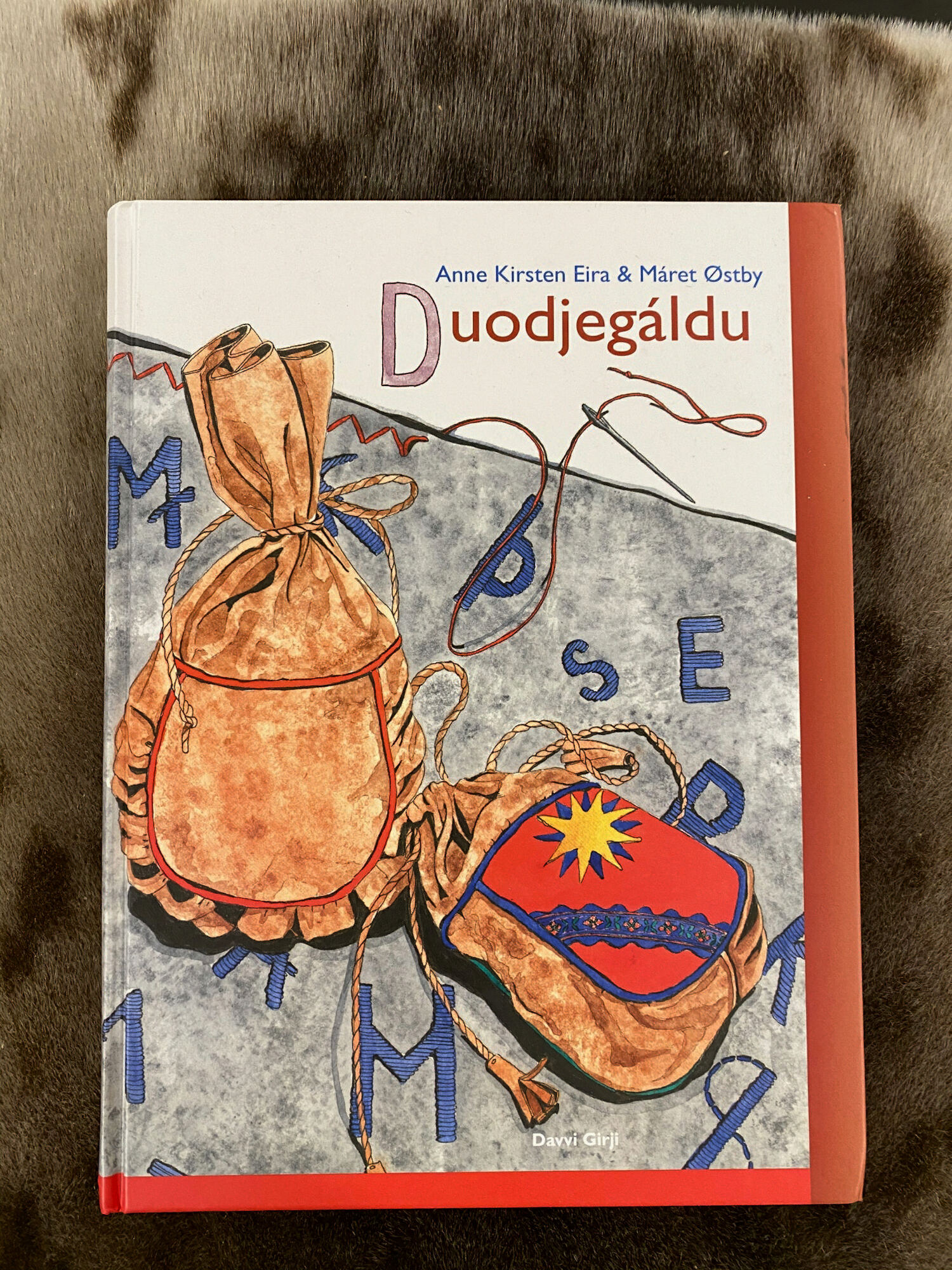

“Some twenty years ago I was part of a jury for an artist organization. One of our tasks was to select members based on their applications. One person had applied and submitted their work. All the works were eye-catching and nice. When the time came to decide whether the person should be granted membership, we requested the assistance of a senior member in our organisation, and that member’s verdict was that the work was neither original nor innovative, and that it was a collective handcraft effort without ‘sufficient individual innovation’. Consequently, we declined that membership application. I have reflected on that decision numerous times, thinking that, if we had considered the work from a duodji perspective, then the decision would have been different, since, as a duojár, the applicant had impressive and innovative pieces of works. But on this occasion, in the context of that art organisation, we judged the work according to the criteria of a field which did not recognise these personal qualities.”

Gunvor Guttorm: Creativity, improvisation and innovation in cultural expressions, 2020-04-20

“We often think of creativity as linked to particular individuals with a particular and innate capacity for creativity, and that their work emerges from an ‘abundance’ of new ideas. However, a lot of recent research has focused on other aspects of human interaction that affect creativity (see e.g. Guttorm 2010; Kaufmann 2008; Svašek 2010: 63). One question that has been asked is whether it is possible to talk about creativity in general and universally applicable terms. Kaufmann warns against understanding creativity as something that is universally the same, since much of the research on the subject has been done in a Western context (Kaufmann 2008: 149).”

Gunvor Guttorm: Creativity, improvisation and innovation in cultural expressions, 2020-04-20

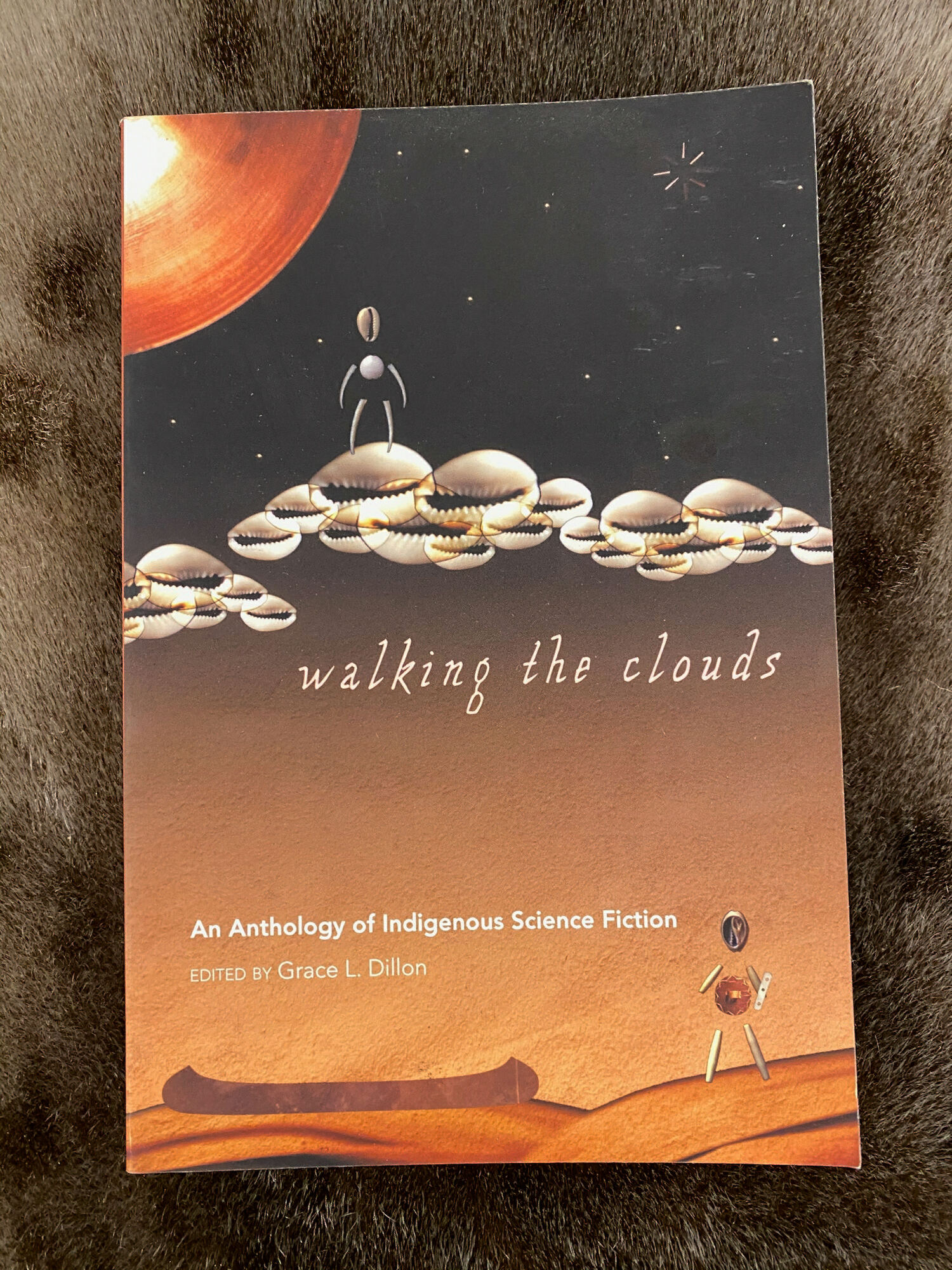

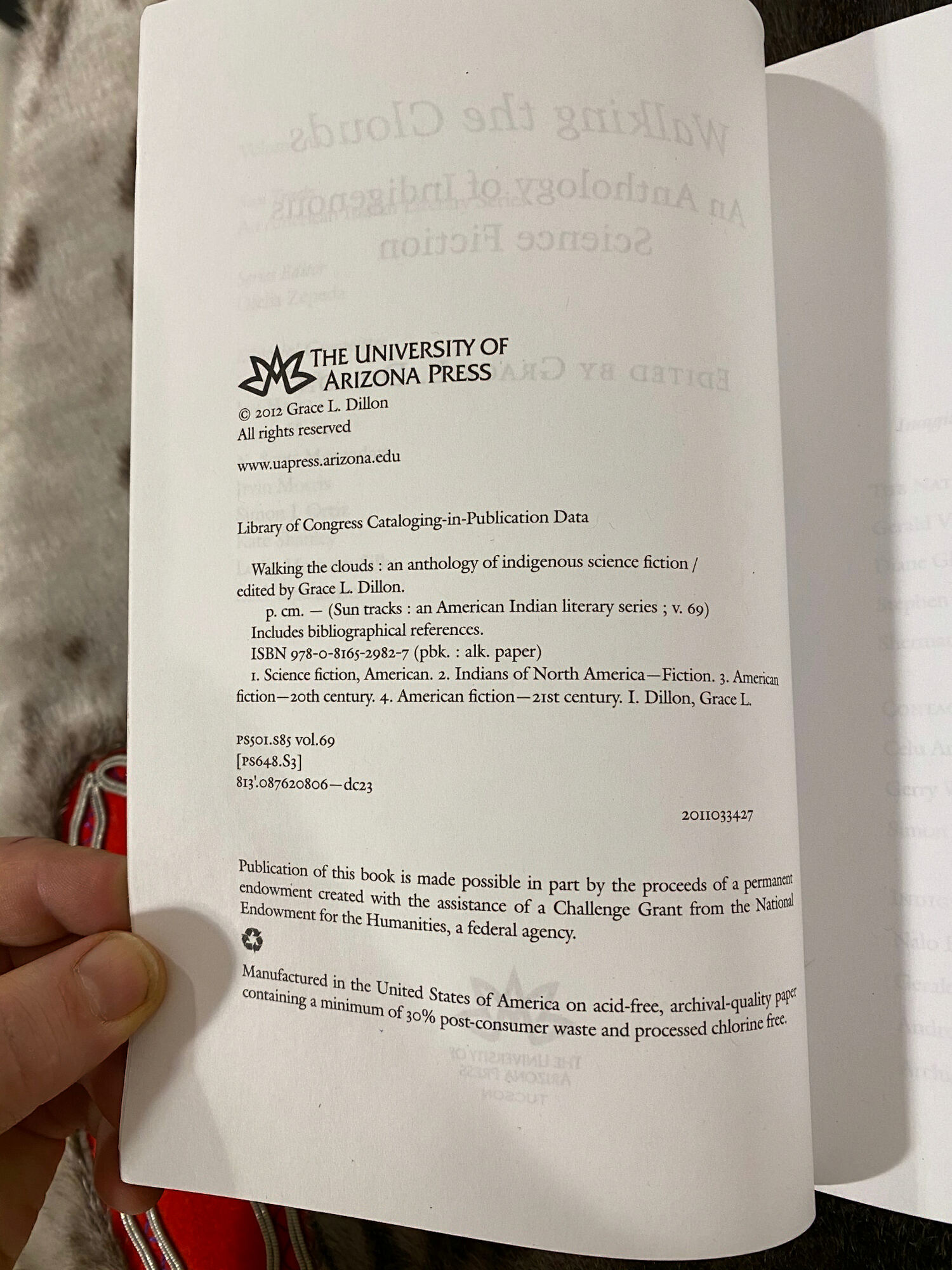

“There have been multiple representations of indigenous cultures in science fiction, Star Trek: Voyager’s first officer Chakotay being a recent example, and yet there are often significant issues involving stereotyping within a broader western narrative. In this way, by directly facing the troubled history of colonization through various cultural outlets such as literature and film, as Brian Attebery writes:

‘...cultural interactions depicted within science fiction are laden with longing and guilt. The indigenous Other becomes part of the textual unconscious – always present but silenced and often transmuted into symbolic form...[as] the genre within which concepts of the future are formulated and negotiated, science fiction can imply, by omitting a particular group from its representations, that the days of that group are numbered.’ (Attebery 2005, 385).”

David T. Fortin, Laurentian University, Sudbury, Ontario: Indigenous Architectural Futures: Potentials for Post-apocalyptic Spatial Speculation,

“The representation and discussion of the future in architecture has remained

David T. Fortin, Laurentian University, Sudbury, Ontario: Indigenous Architectural Futures: Potentials for Post-apocalyptic Spatial Speculation,

almost exclusively within the realm of western science fiction where technological

determinism, either utopian or dystopian, is the primary force for social and cultural change

and adaptation.”

“Freud was not a Freudian, Marx was not a Marxist and Bob is not a Postmodernist.” – Robert Venturi

Andrea Tamas: Interview: Robert Venturi & Denise Scott Brown, 2009

“Less is a bore.” – Robert Venturi

Andrea Tamas: Interview: Robert Venturi & Denise Scott Brown, 2009

“When circumstances defy order, order should bend or break: anomalies and uncertainties give validity to architecture.” – Robert Venturi

Andrea Tamas: Interview: Robert Venturi & Denise Scott Brown, 2009

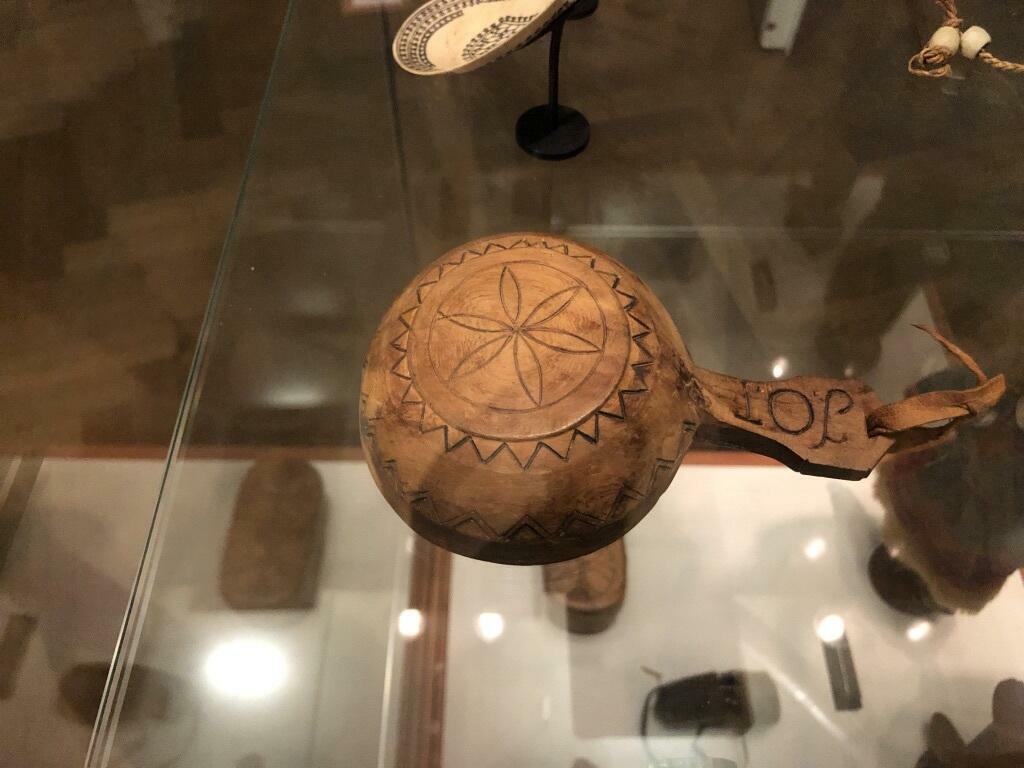

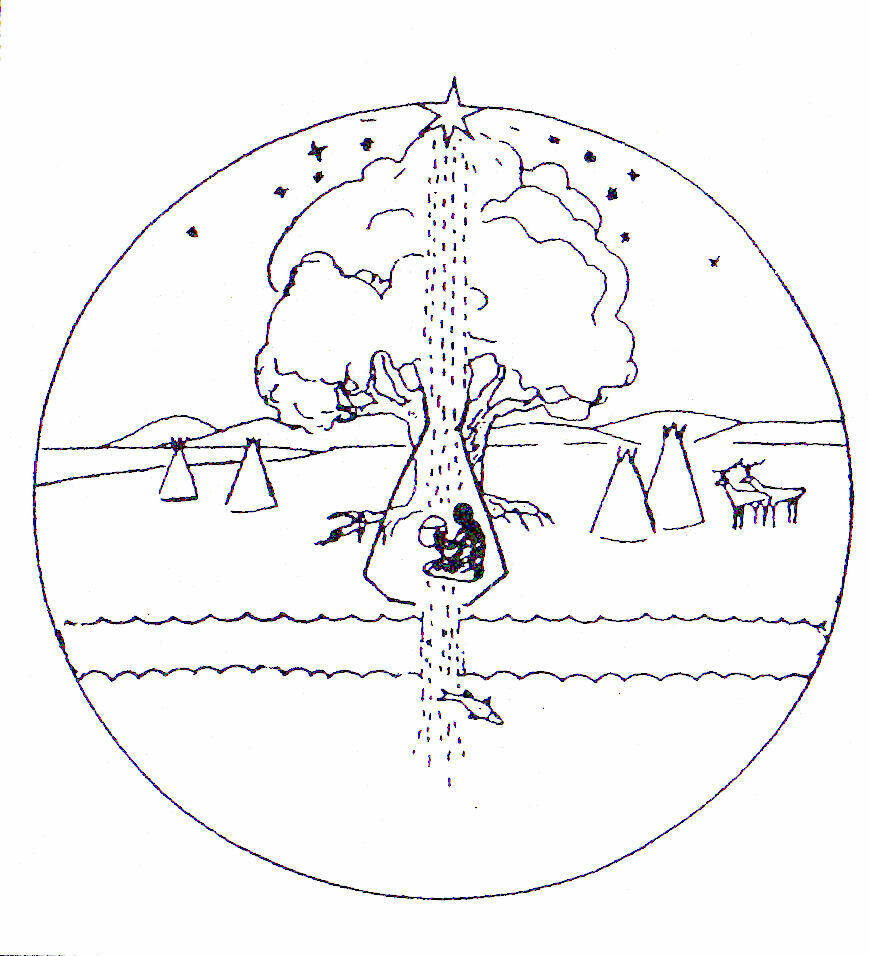

“That shining circle can be seen as a symbol of the Sámi and other Indigenous Peoples’ cyclical understanding of time and circular resource management – ideas we should all embrace if we are to ensure humanity’s survival on this planet.”

Mariann Enge: Just Breathe, 2020

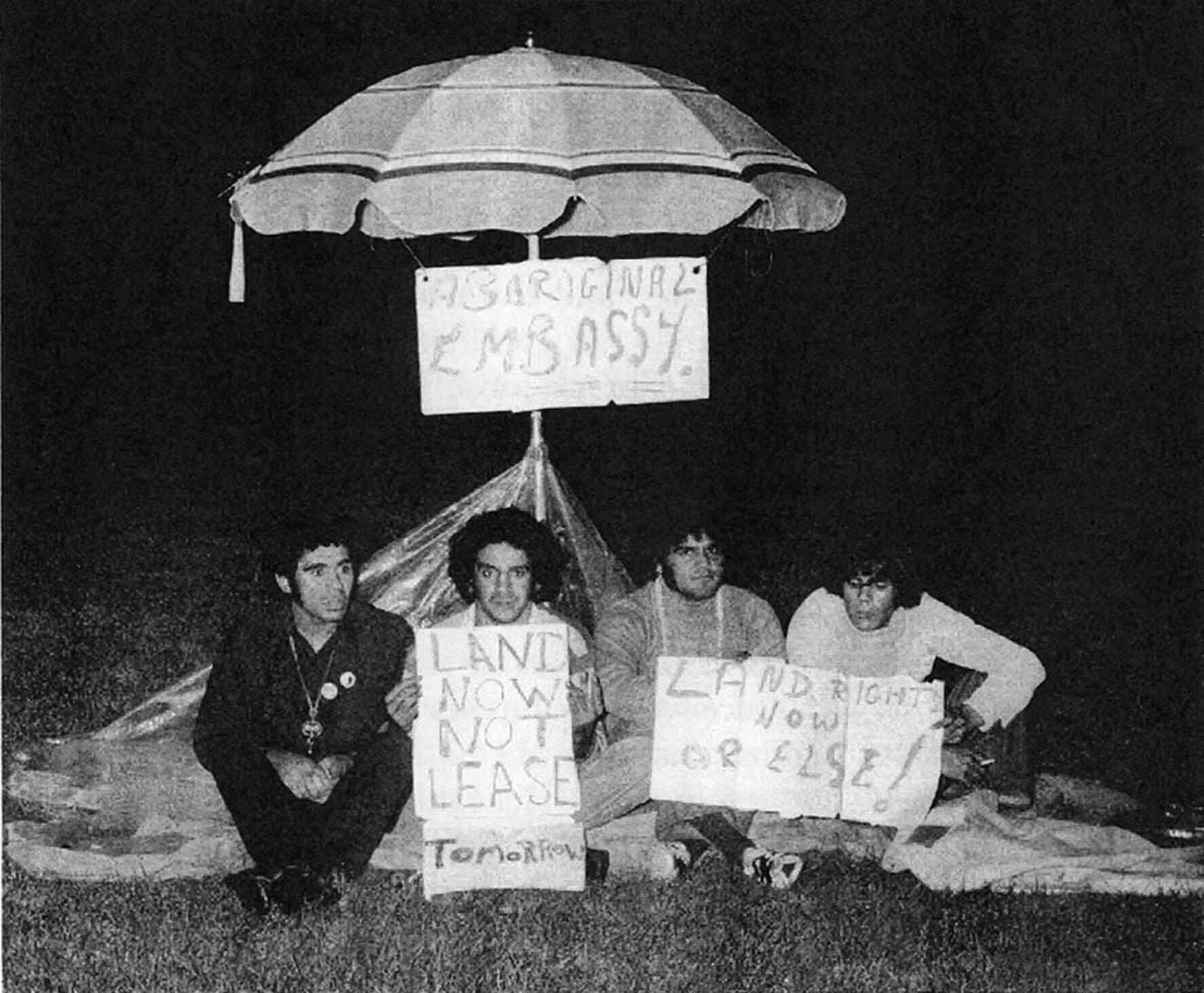

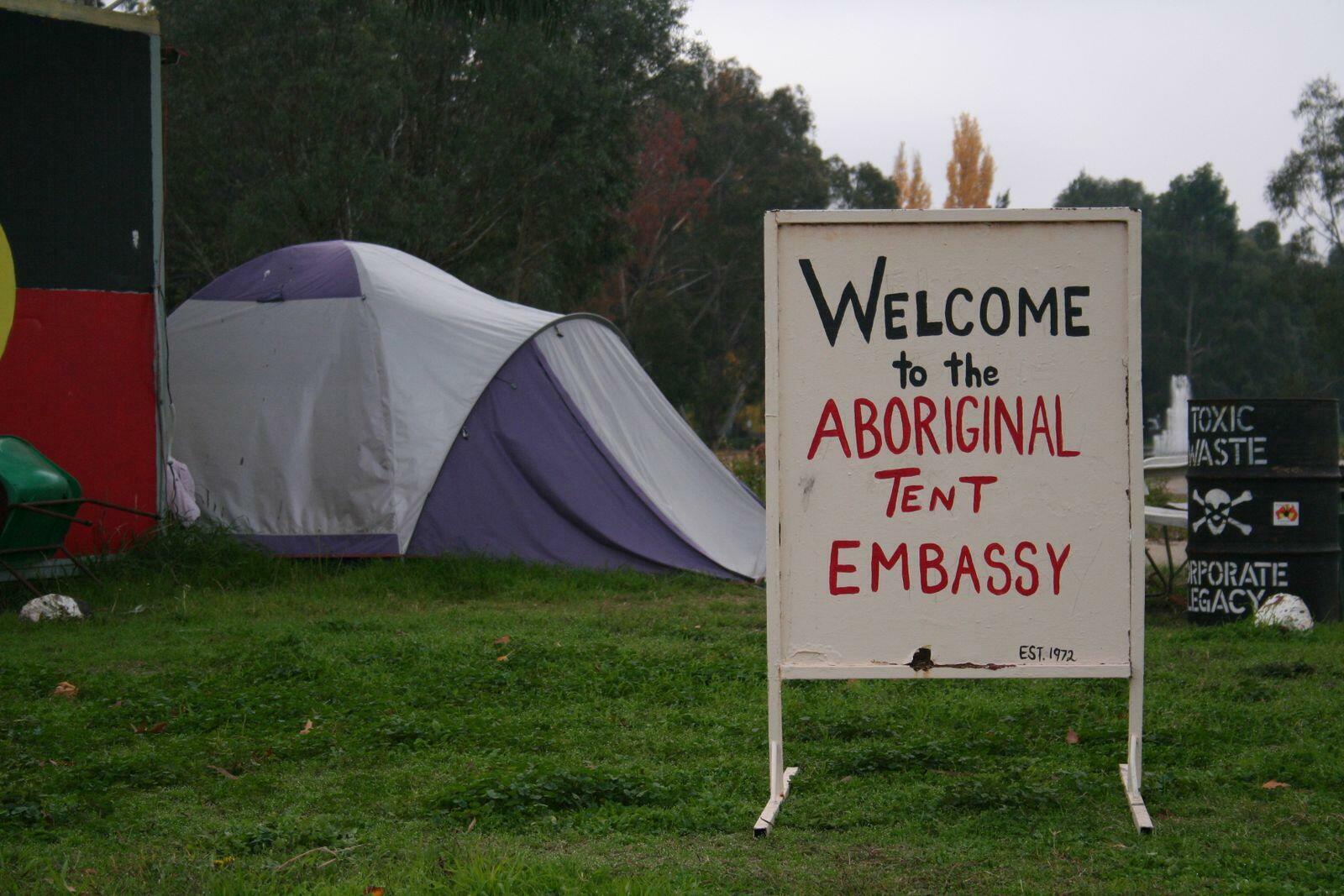

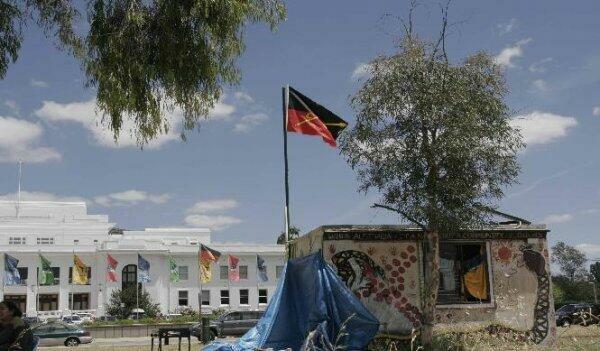

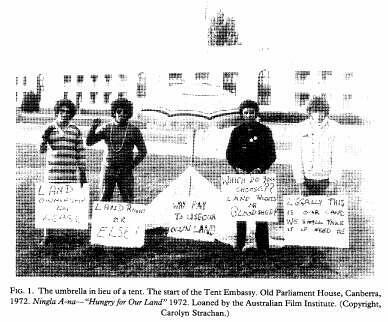

: Land Rights News Northern Edition, 2016-01-29

“The relation of people to their environment is essentially an active one. They act upon it - they breathe the air; they can physically alter it; attach symbolic properties to it; and focus their senses upon certain parts of it. Likewise, the environment acts upon people. It provides a regular continuum of changing sensory stimuli; it restricts and directs human movement and activity through its physical barriers and open spaces; it affects human comfort and energy.”

Paul Memmott, School of Geography, Planning and Architecture, The University of Queensland: Lardil Properties of Place: An ethnological Study in Man-environment Relations, 1980

In Lillelord, Norway’s contemporary master Johan Borgen (1902-79) demonstrates his belief that our lives tend toward schizophrenia. Wilfred Sagen at fourteen is still a perfectly turned out, impeccably behaved "Little Lord Fauntleroy" to his family, but to his teachers he is a disruptive enigma and, to a pack of Oslo street urchins, an instigator of crime. In his often desperate search for emotional integration, Wilfred is hampered by an acute and introspective intelligence which only compounds his normal adolescent anxieties. Painfully aware of the split in his own personality, Wilfred longs for wholeness and harmony (personified by the young Jewish violinist, Miriam), but is torn by guilt and the realization that he cannot control either himself or the world.

Johan Borgen: Lillelorden,

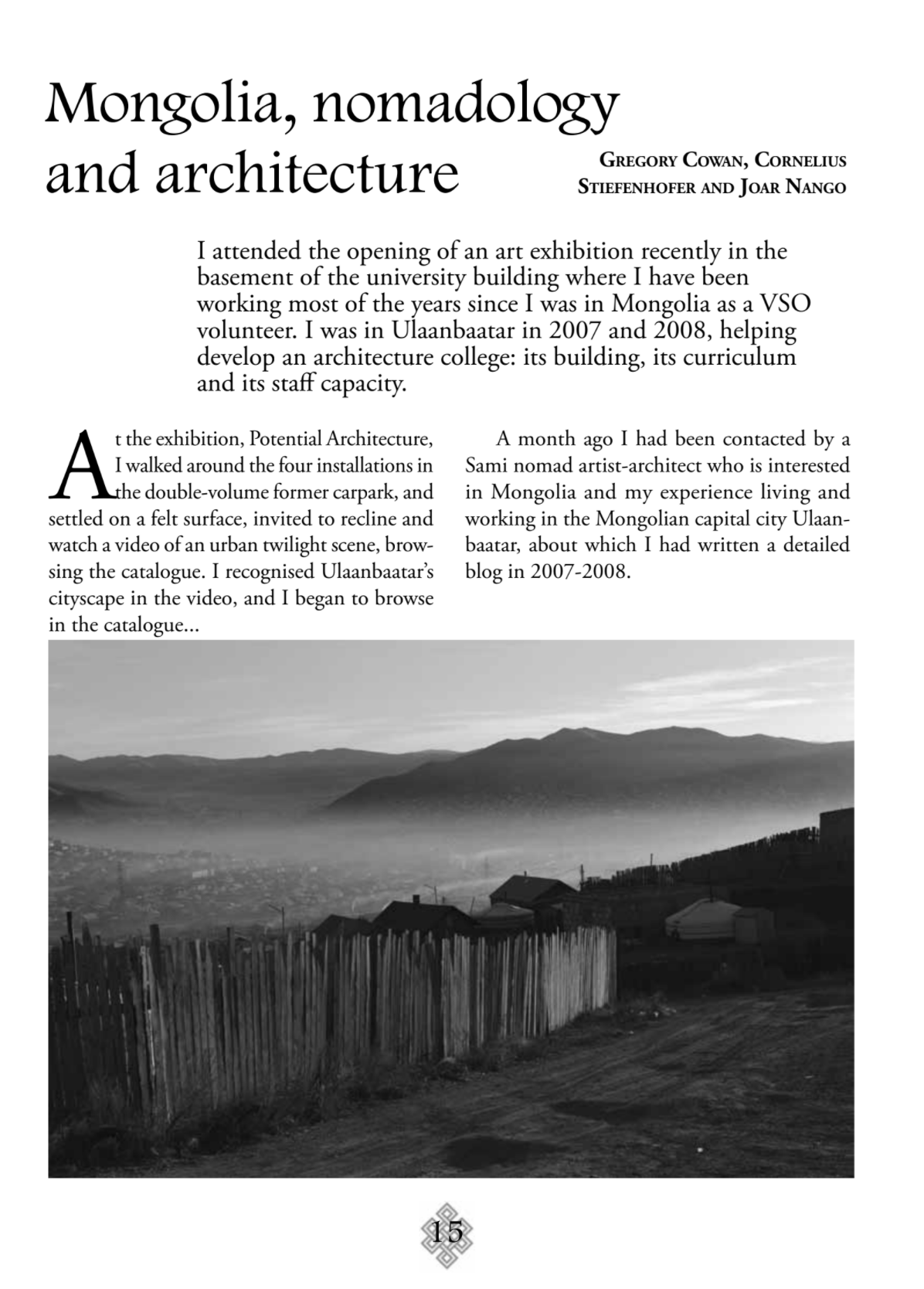

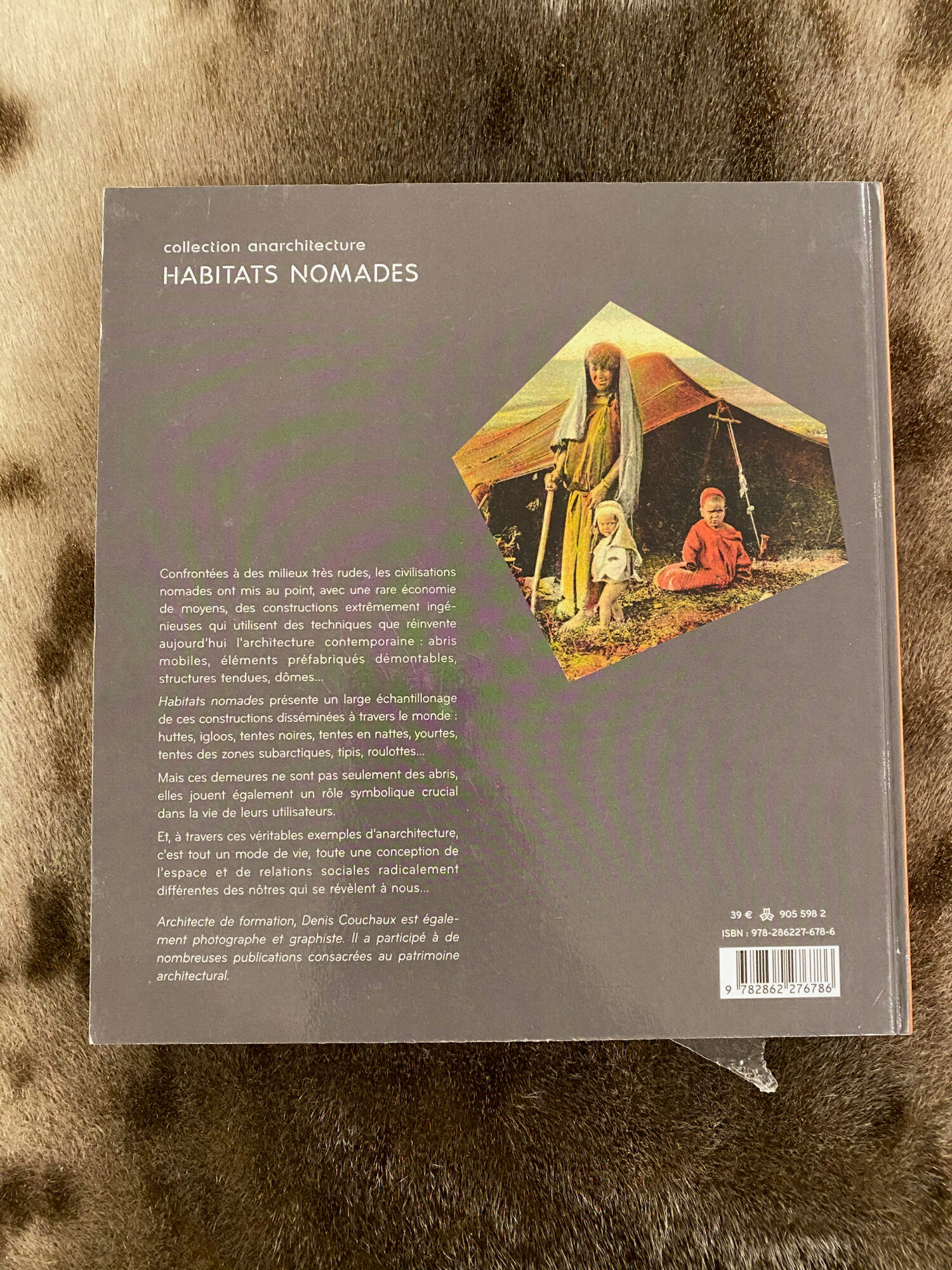

“I met with Joar Nango, the Sami architect, as he described himself and we talked about Mongolia, working there, and about music and nomadic life. He recorded our conversation on a digital audio recorder.”

Gregory Cowan, Cornelius Stiefenhofer and Joar Nango: Mongolia, Nomadology and Architecture,

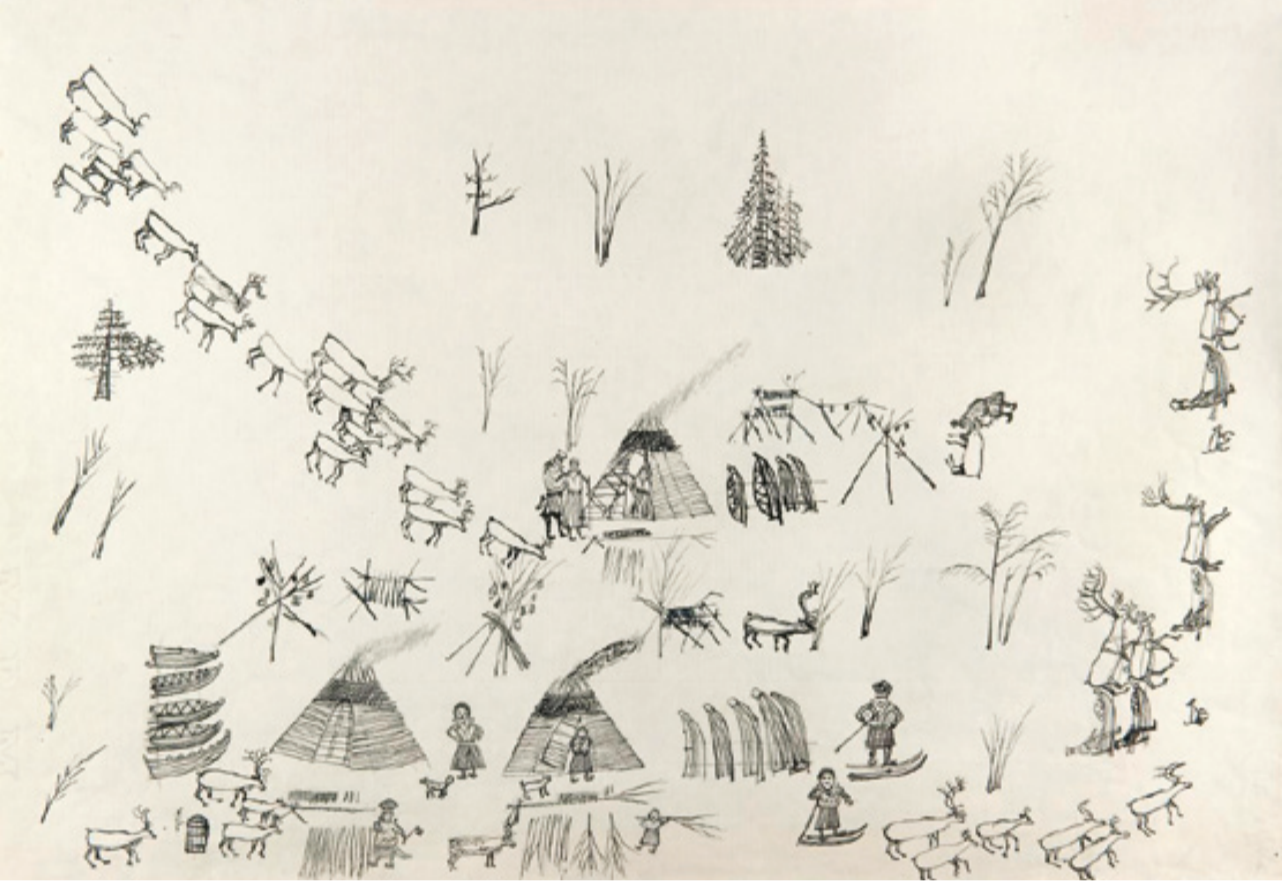

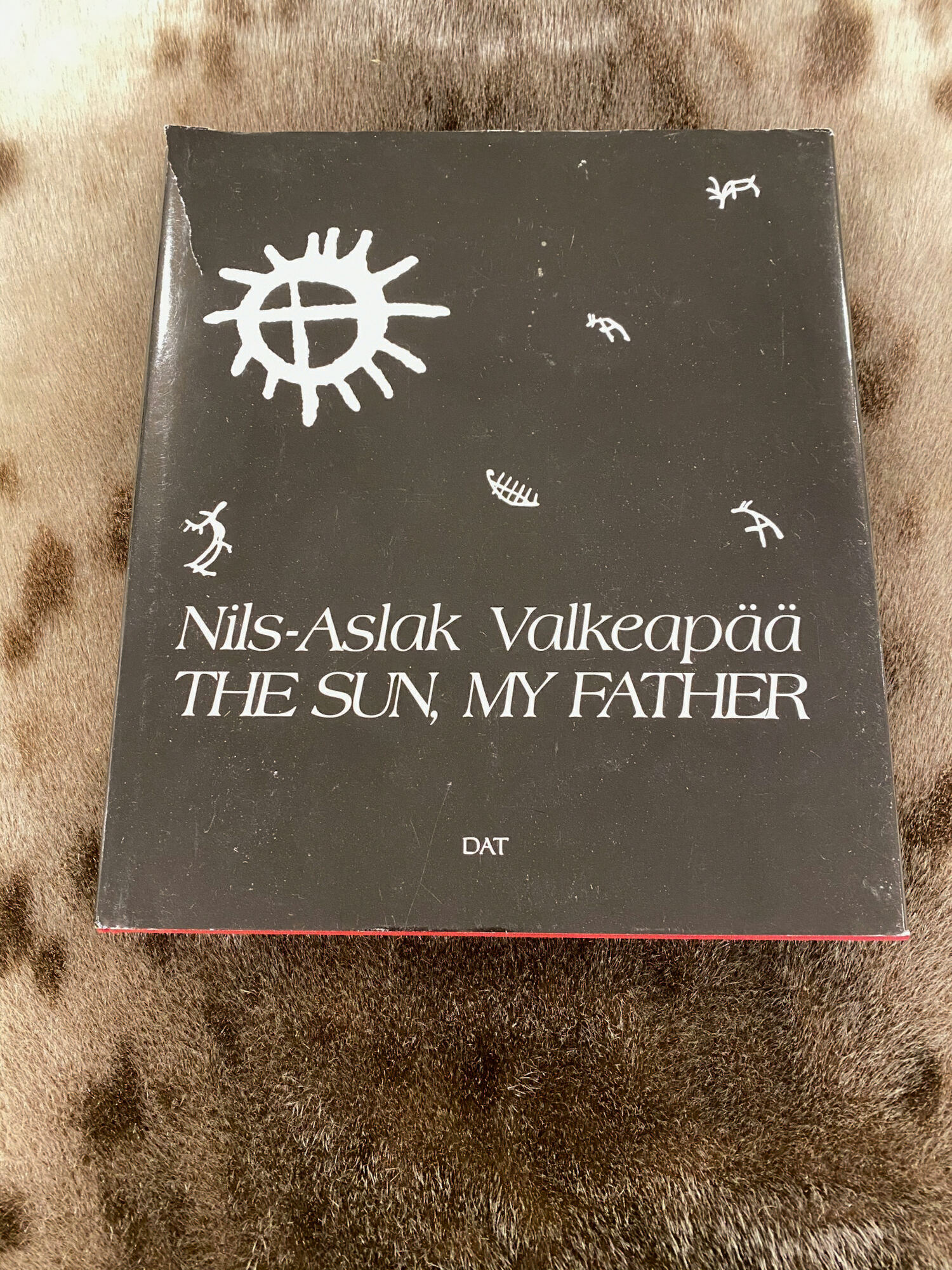

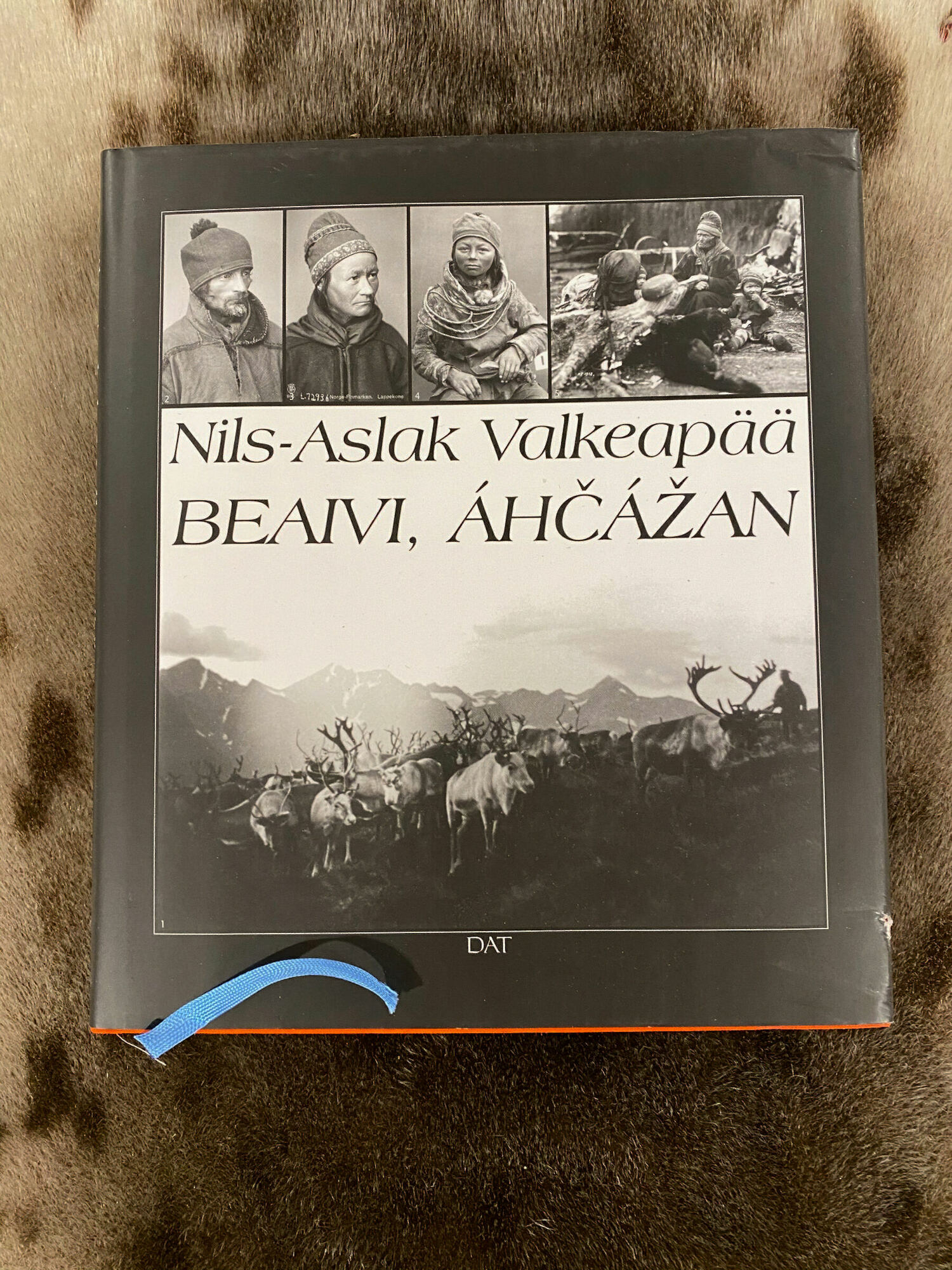

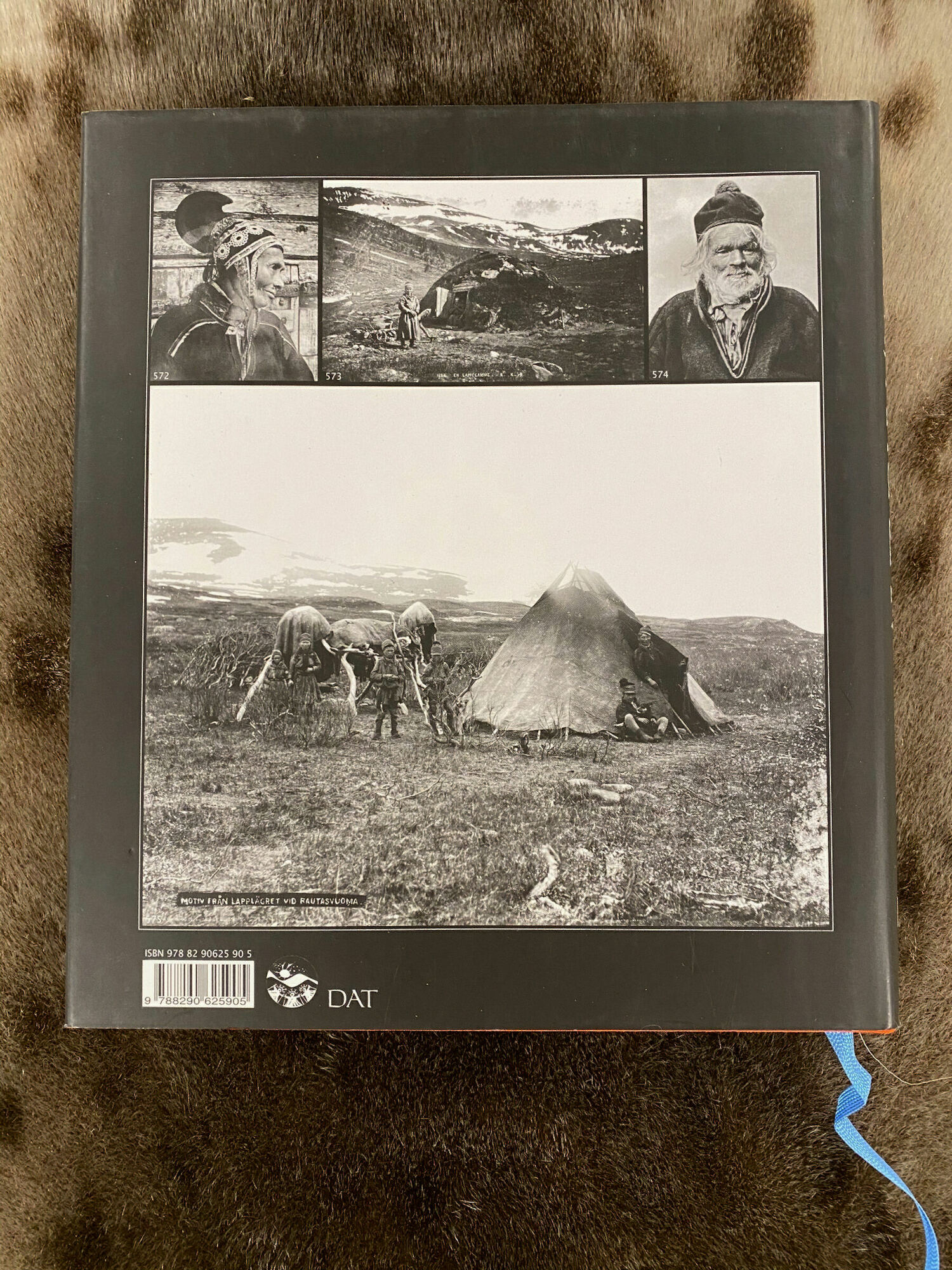

Can you hear the sounds of life

In the roaring of the creek

In the blowing of the wind

That is all I want to say

That is all

Nils-Aslak Valkeapää: Trekways of the Wind,

"No one knows my struggle, they only see the trouble." -Tupac Shakur

Joar Nango: Pamphlet, 2016

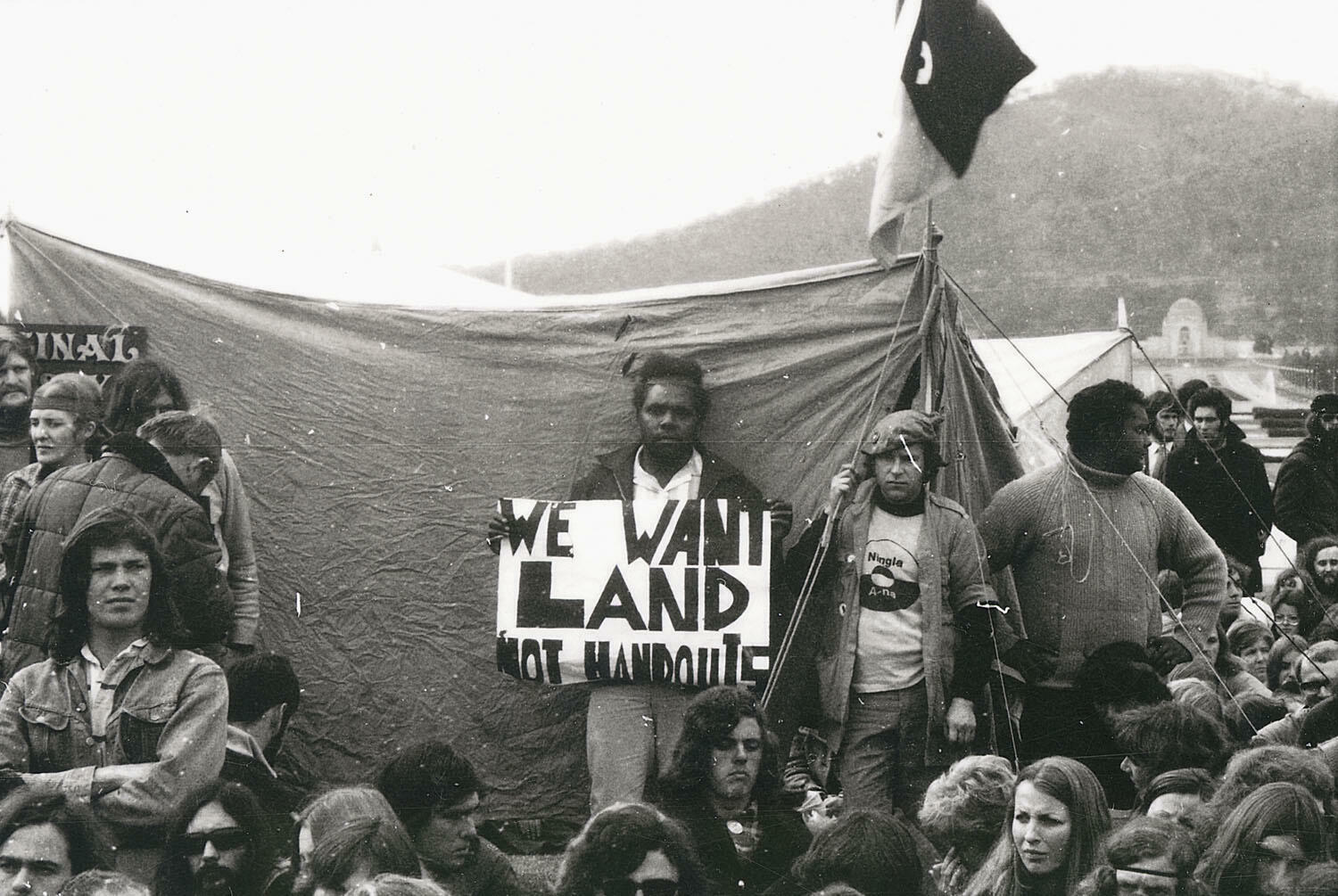

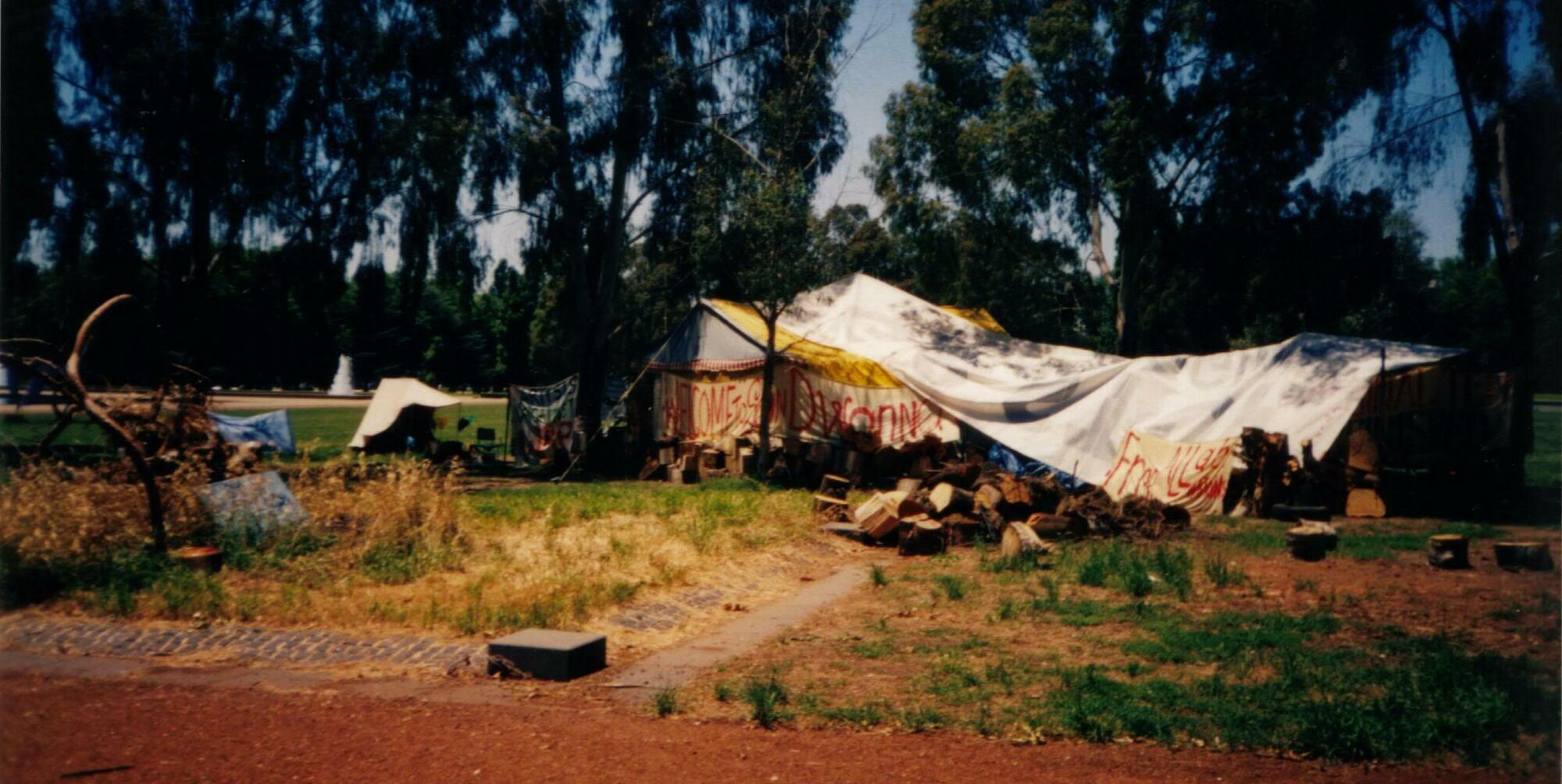

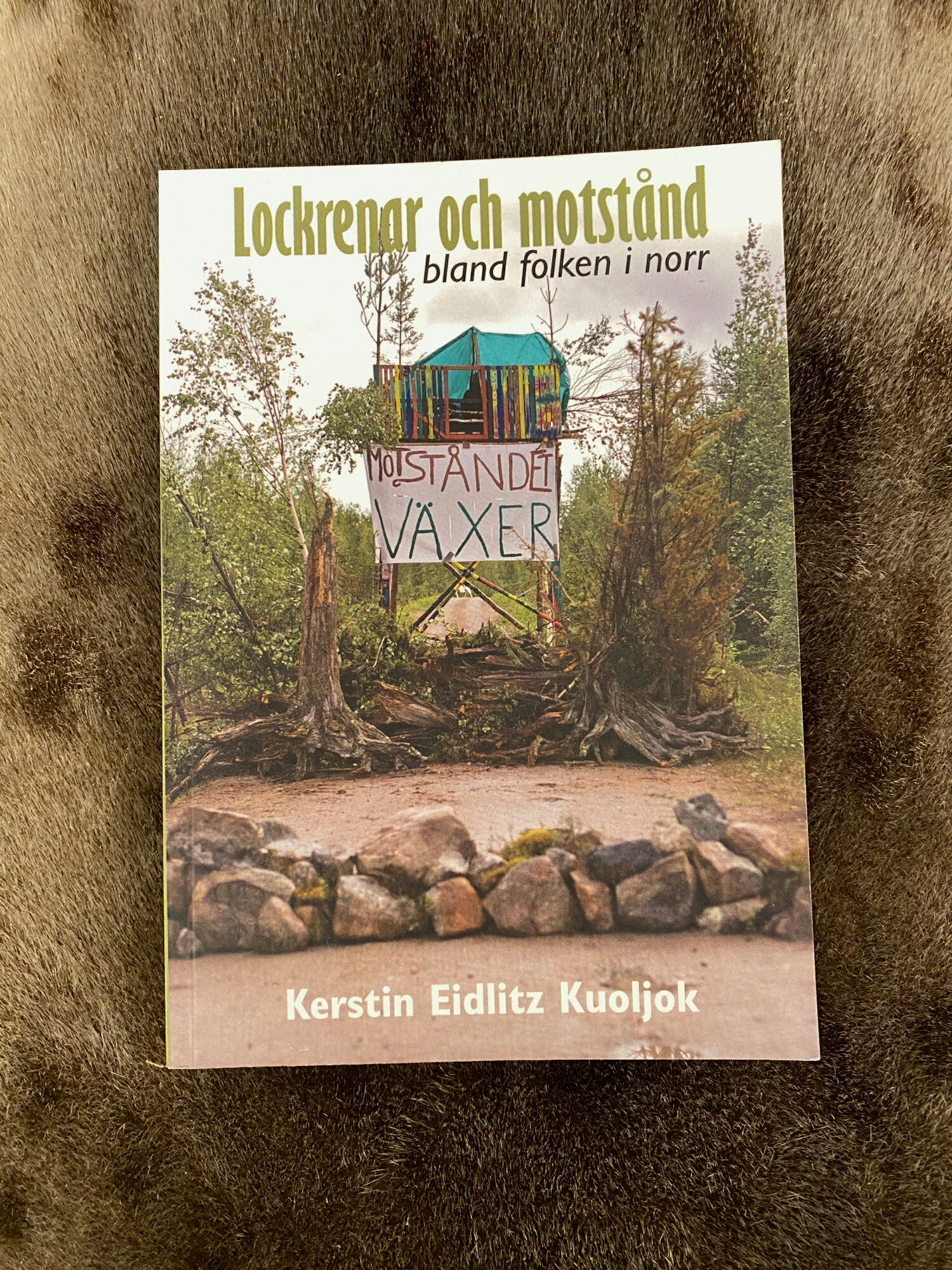

”Protestarkitekturen framstår i dag som et interessant kollektivt rom, hvor ’arkitekter’ egenhendig fikk utforske konstruksjonen av kollektiv identitet.”

Joar Nango: Arkitektur N: Oslo Arkitekturiennale, 2010

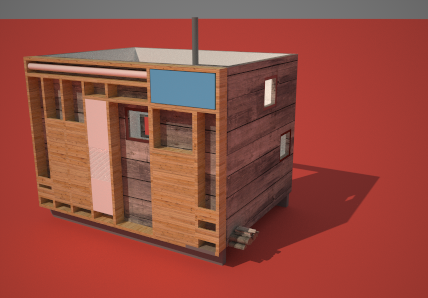

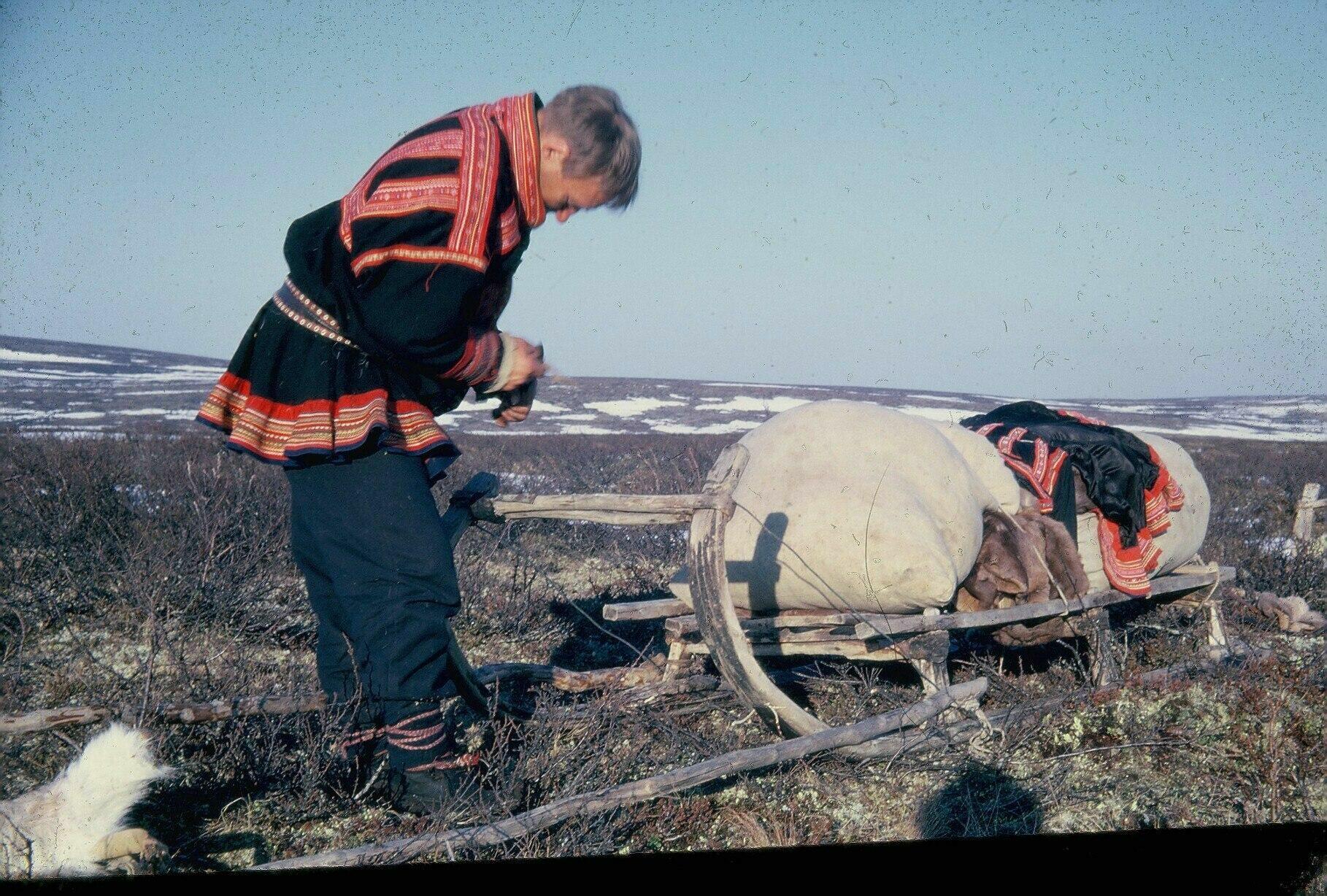

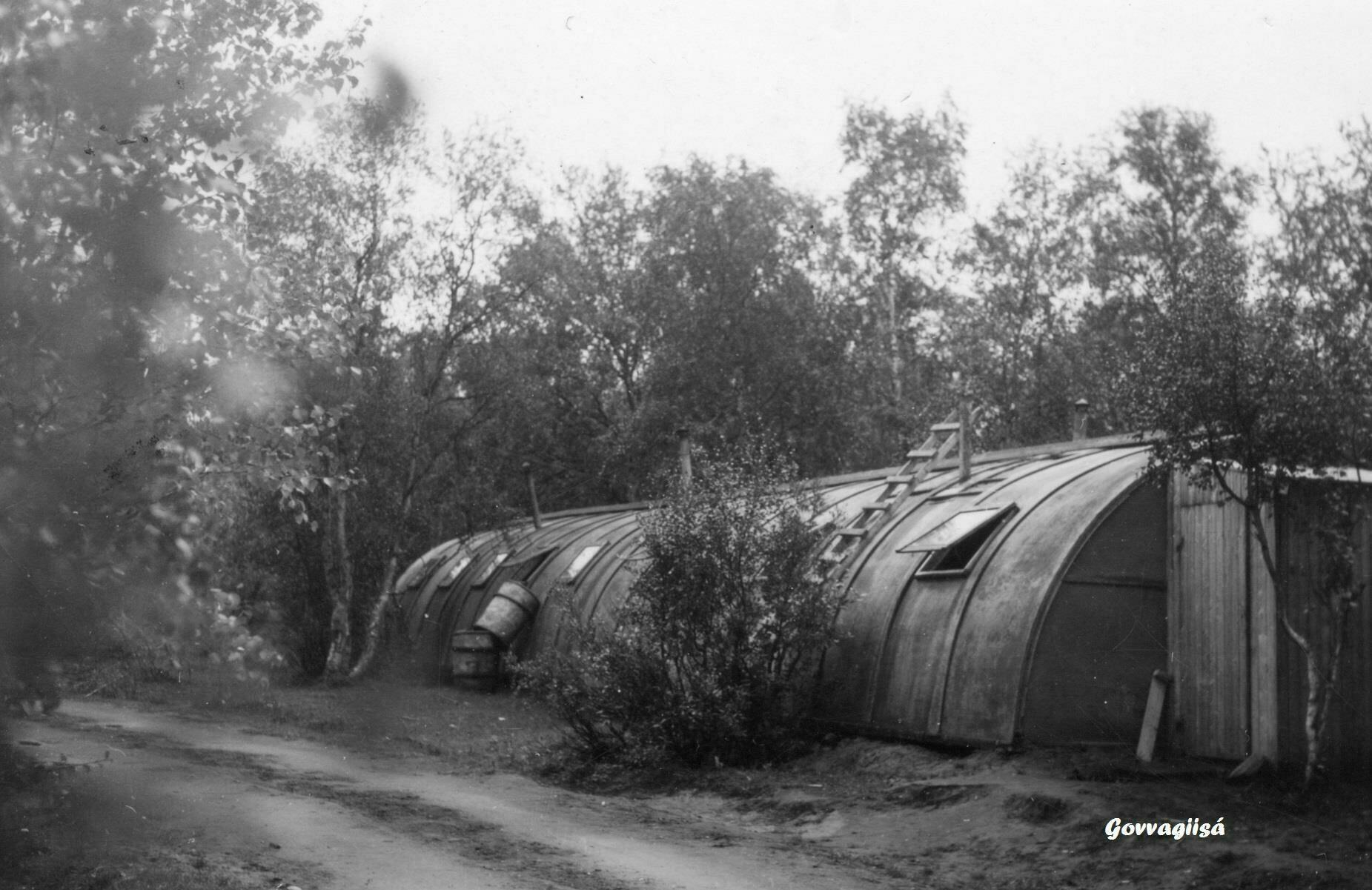

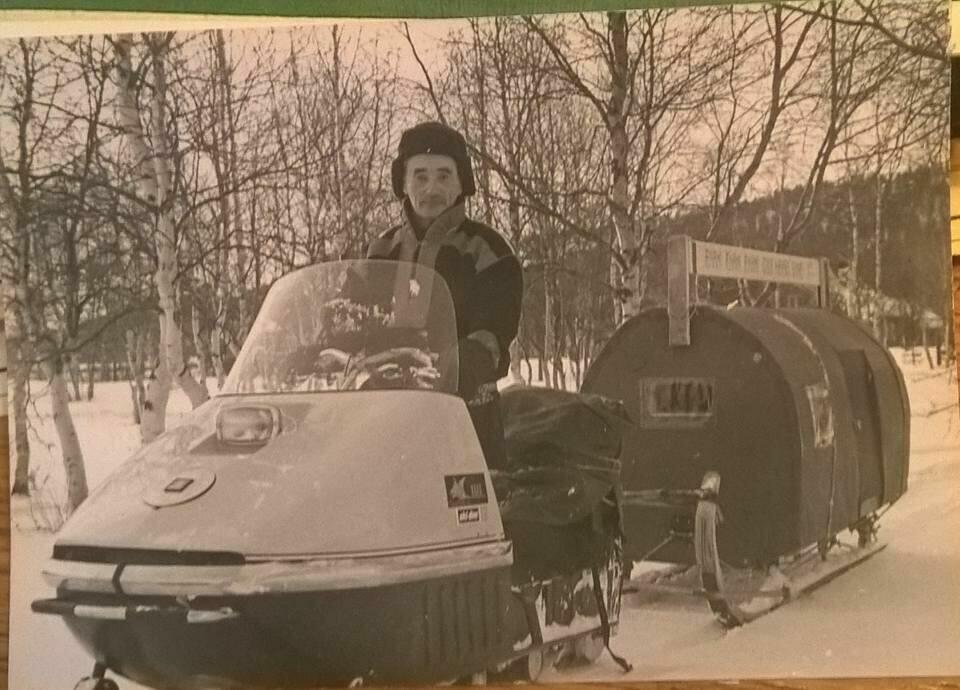

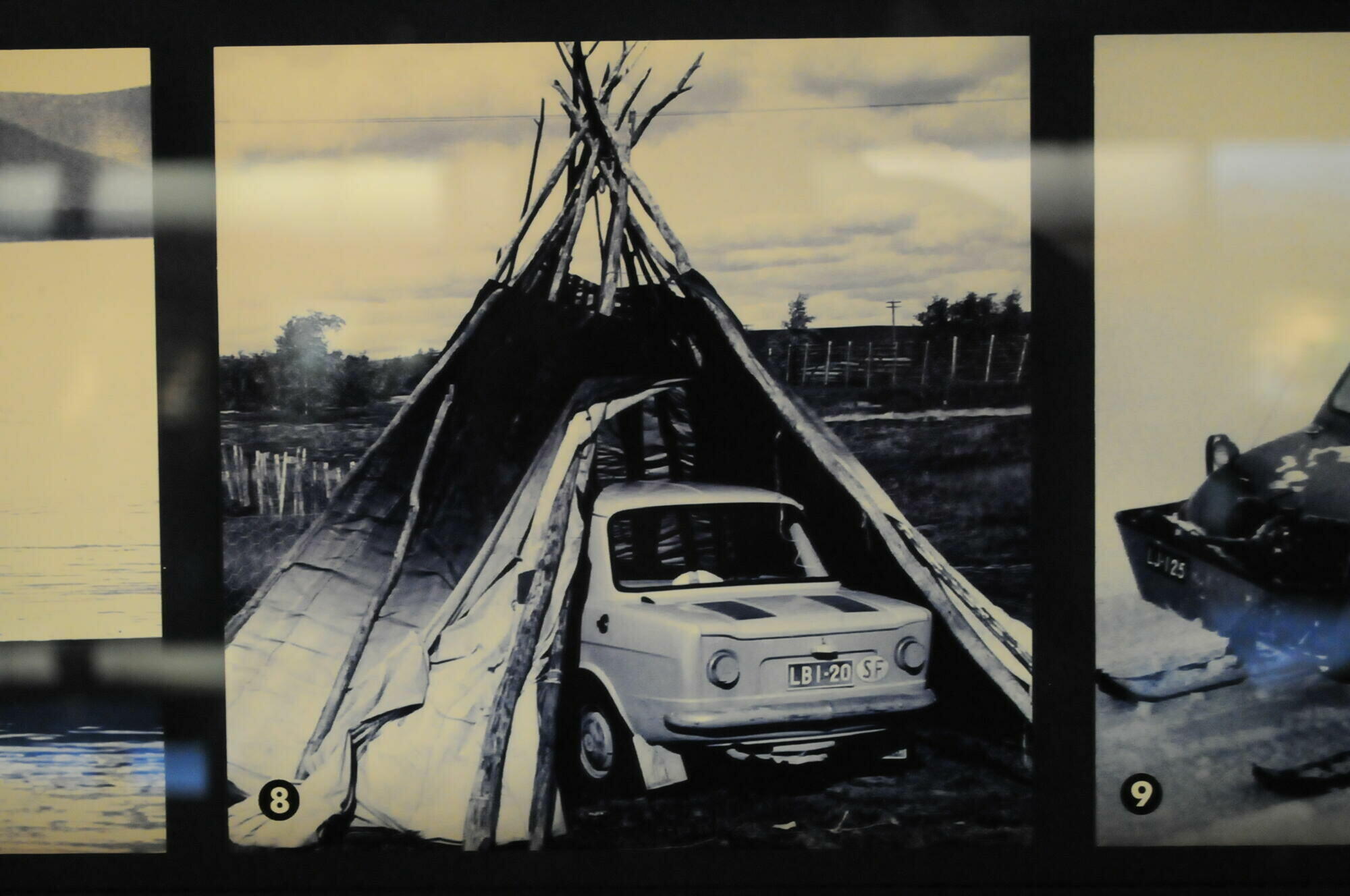

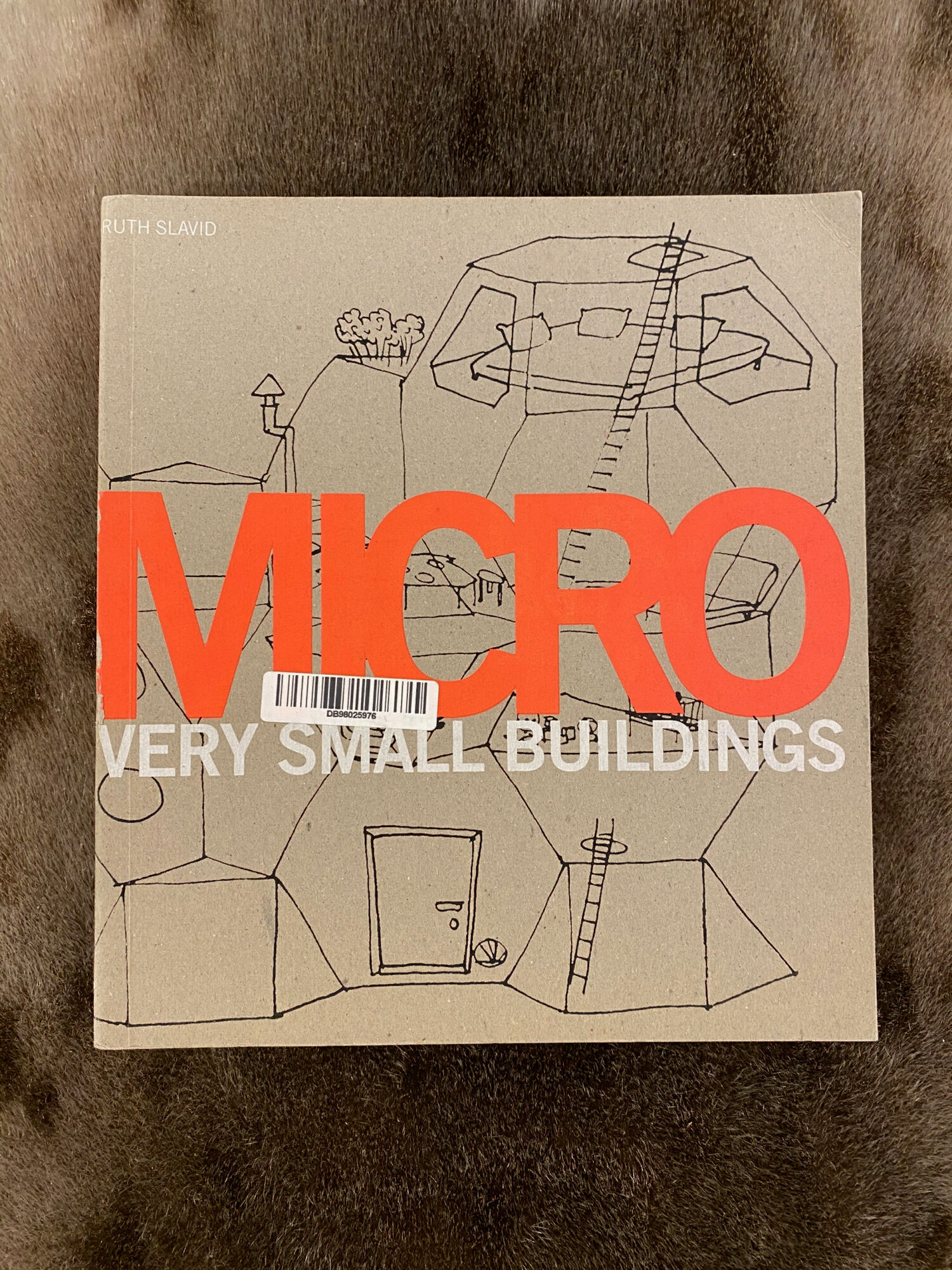

“I am into nomadic architecture. I like to observe how materiality and movements connect to one another; in a spatial way, as cultural output, and of course aesthetically. Temporary and improvised structures (from a life on the move) have been the cornerstone of my architectural and artistic practice for a long time. It's something I try to learn from and a knowledge I construct my world through.”

Joar Nango: Pamphlet, 2016

"'There should be as many kinds of houses as there are kinds of people and as many differentiations as there are individuals.' It is this aspect of Wright’s philosophy that resonates

Rebecca Lemire: Organic Architecture and Indigenous Design Tenets: Frank Lloyd Wright in Relation to the Work of Douglas Cardinal, 2013

the strongest with Cardinal. In a statement defining his own organic philosophy, Cardinal writes that 'The potential users of the project provide feedback and direction to sculpt the plan and facilities from the inside out . . . Each cell or space has a particular function, like that of the human body.'"

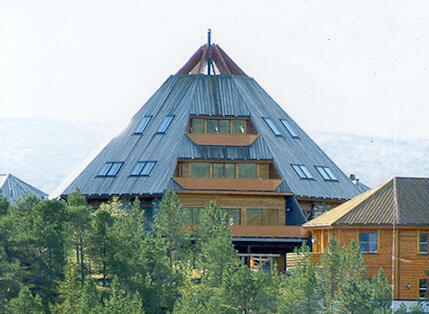

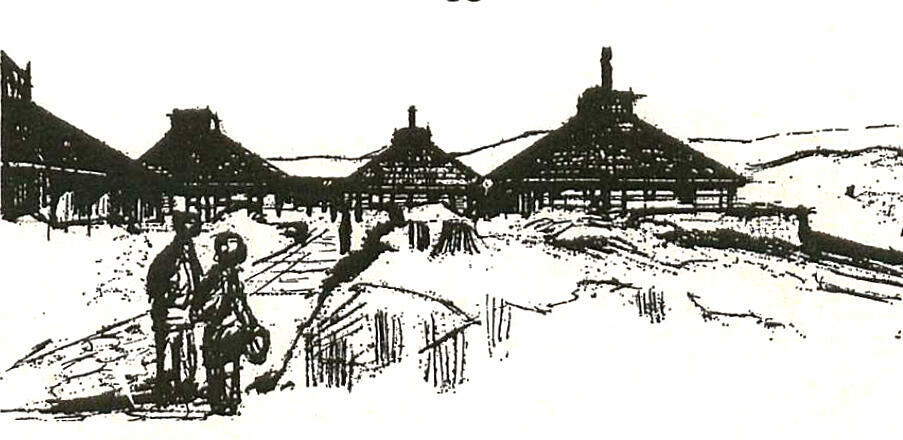

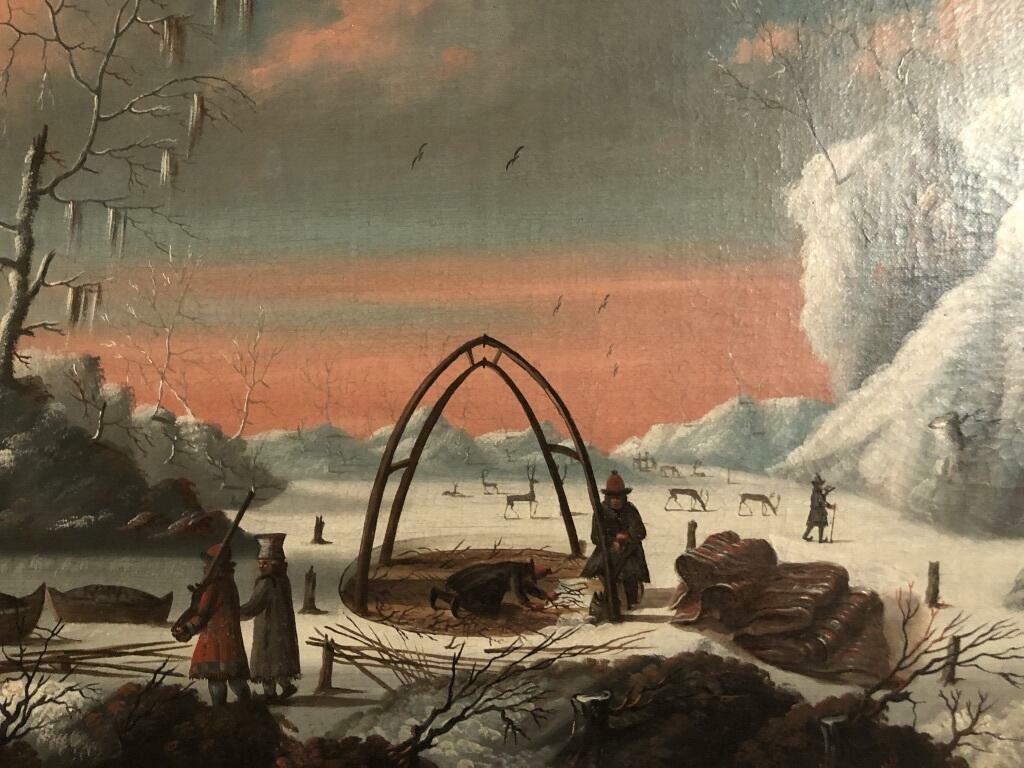

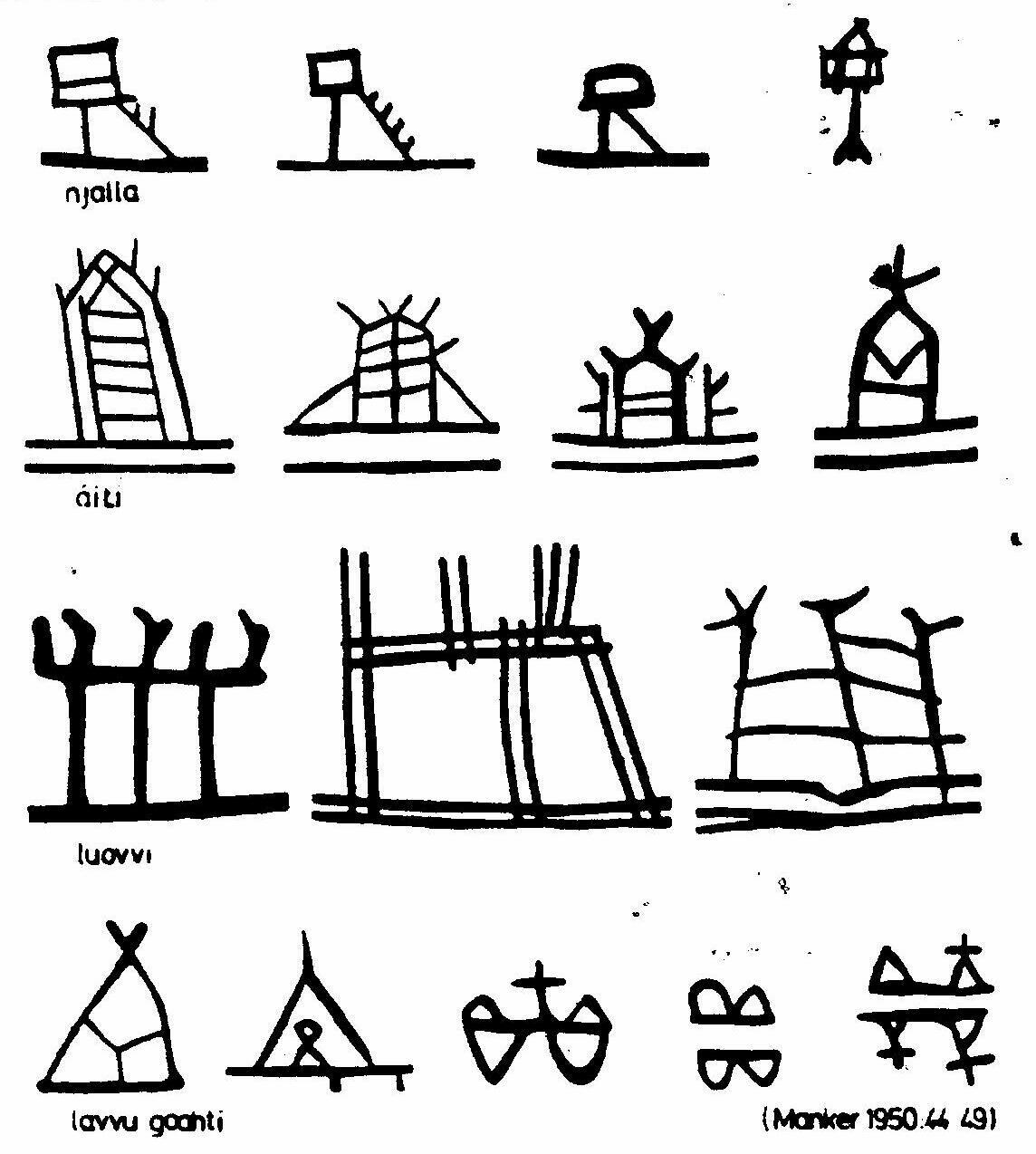

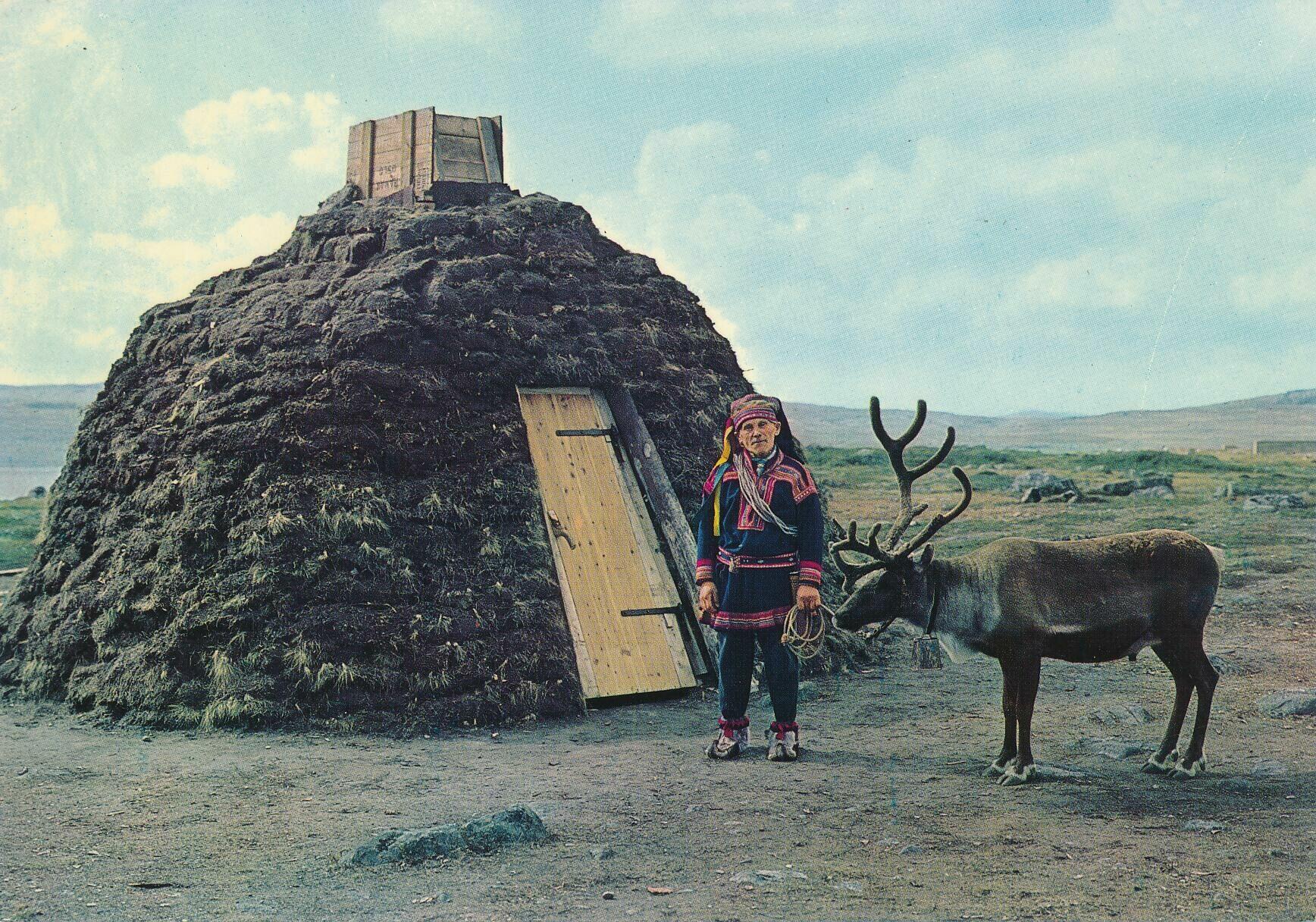

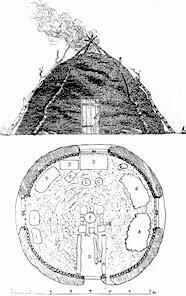

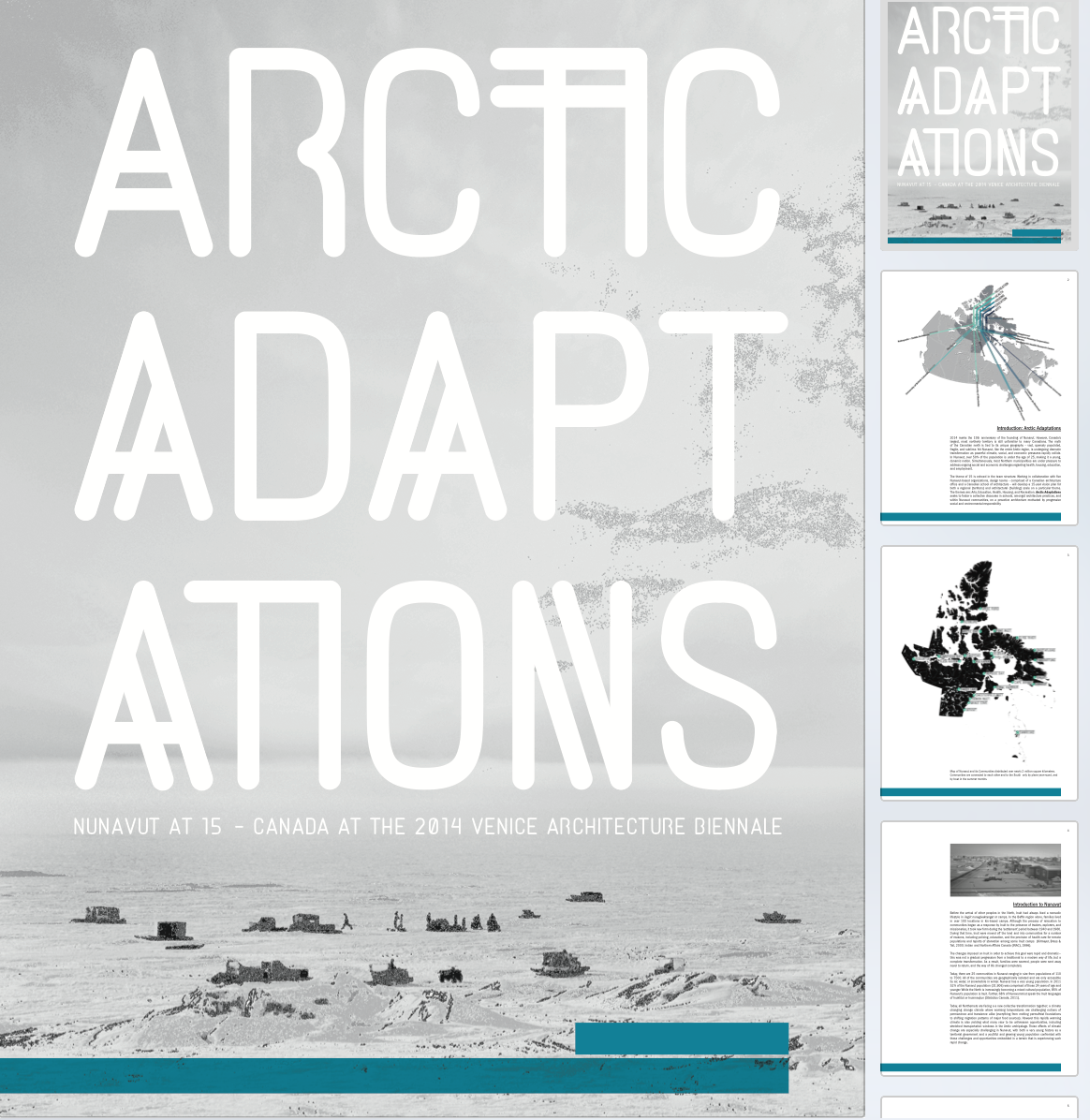

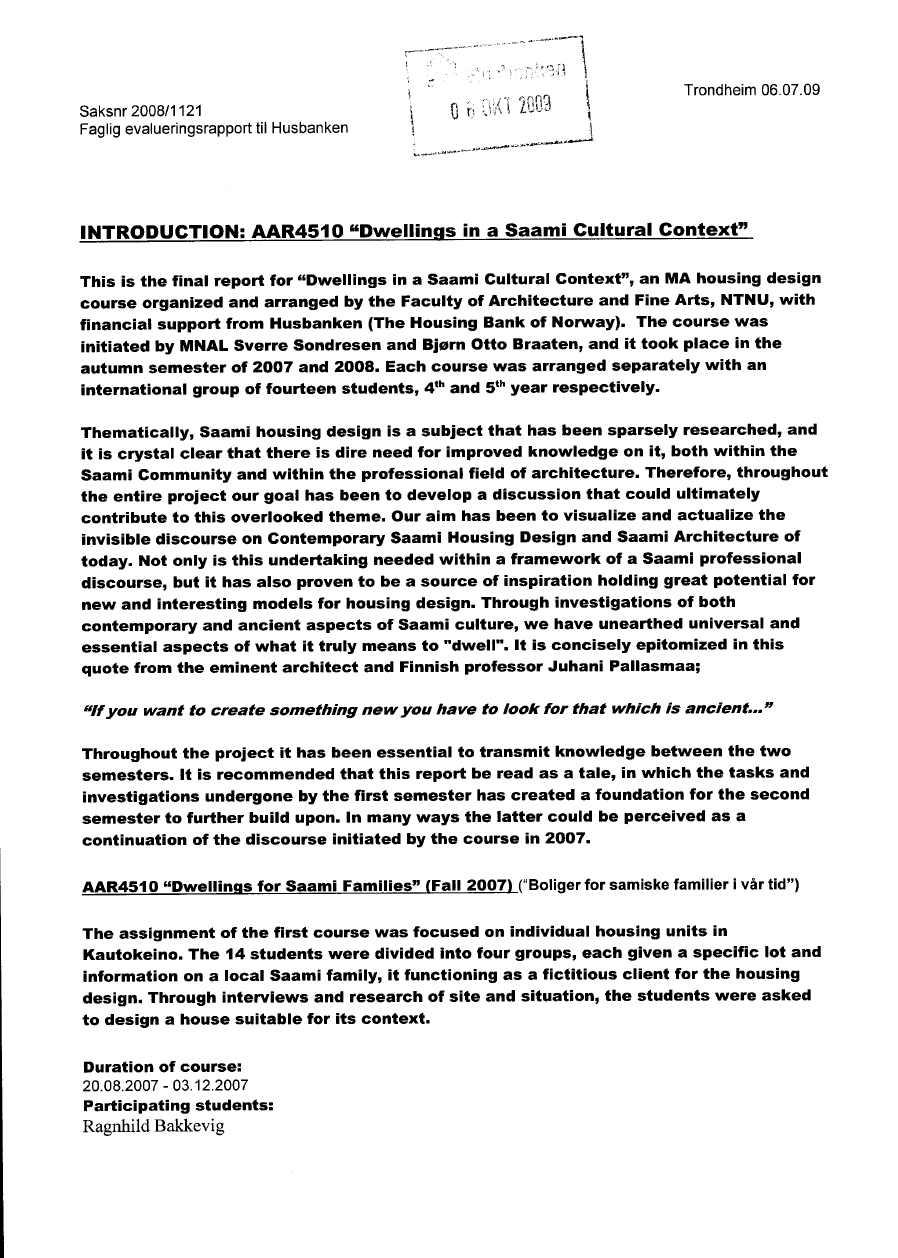

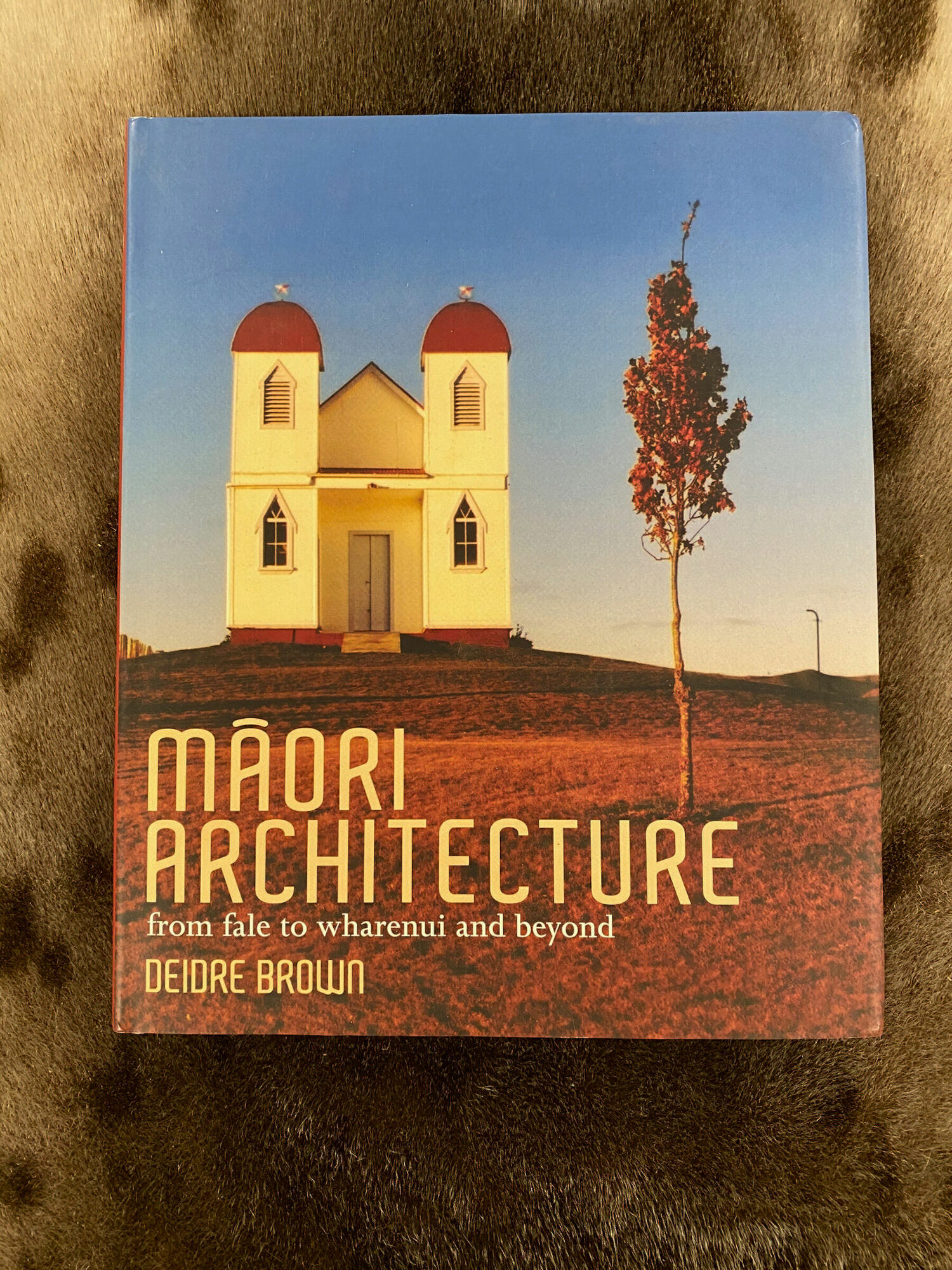

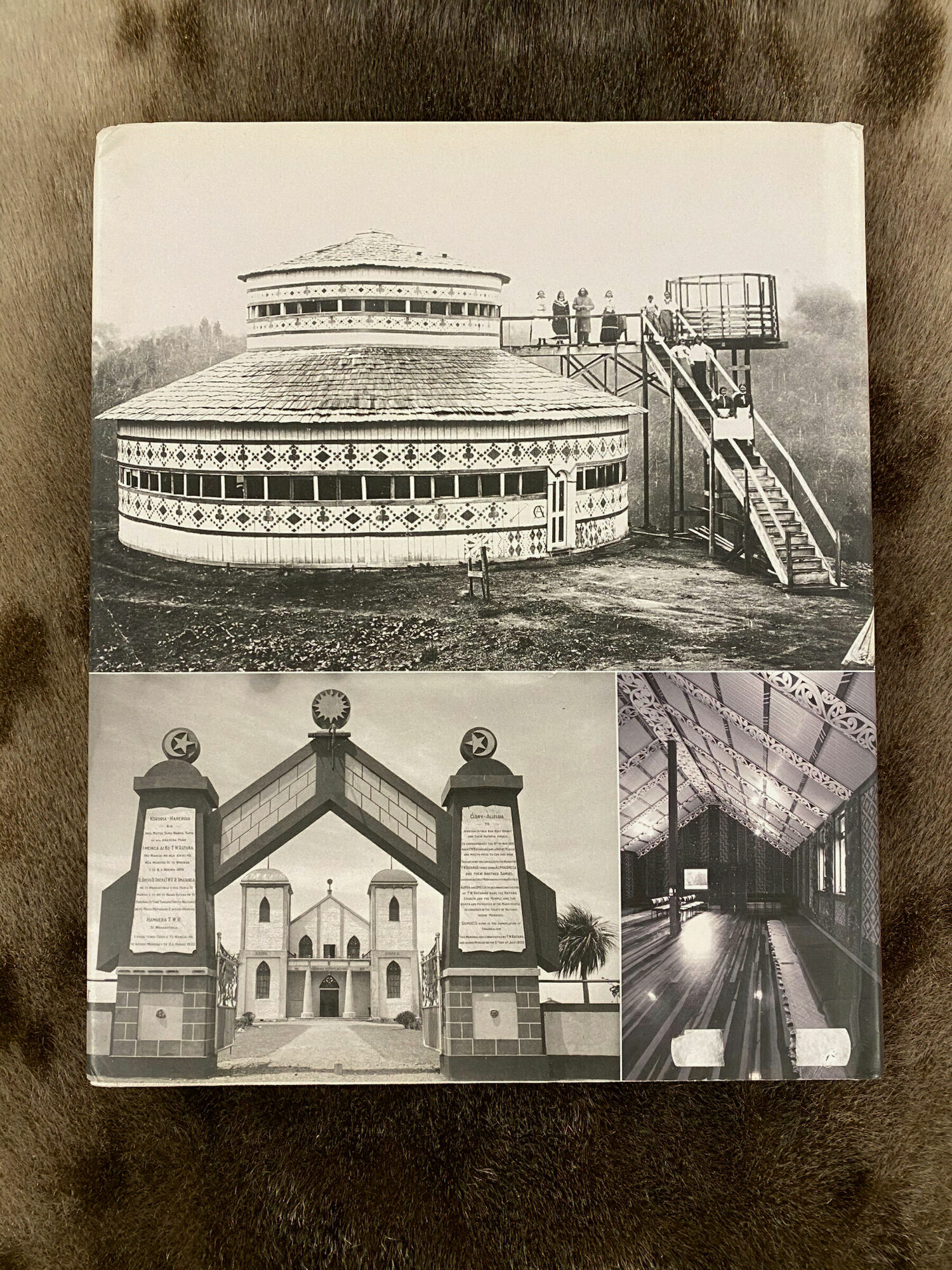

"Our image of the built environment of the Sami territories in the far north is dominated by two preconceptions: on the one hand the image of particular structures like turf huts and the lavvo, the Sami tent, and the reinterpretation of these structures in new public buildings like the Sami parliament building in Karasjok, and on the other hand the spread of anonymous suburban housing that at first glance have no Sami characteristics. Both these conceptions are true, spanning from a low-key attitude to everyday life to the symbolism of monumental architecture, but both are incomplete.

This article discusses the particularities and the familiar traits of Sami architecture and their development. Modern Sami settlements are in fact challenging the way the urban middle class organise and use their domestic environment. A Sami dwelling contains the familiar domestic functions, but in addition it is the setting for a number of other activities, related to both working and an extended social life; the outdoor areas in particular give room for an active and creative way of life. And it is these activities, rather than the static elements of buildings and furniture, that give the places their identity; the structures that bind the Sami settlements together are social, not physical."

Sunniva Skålnes is an architect and researcher, and senior advisor to the Sami Parliament.

Sunniva Skålnes: Samtidig samisk Arkitektur,

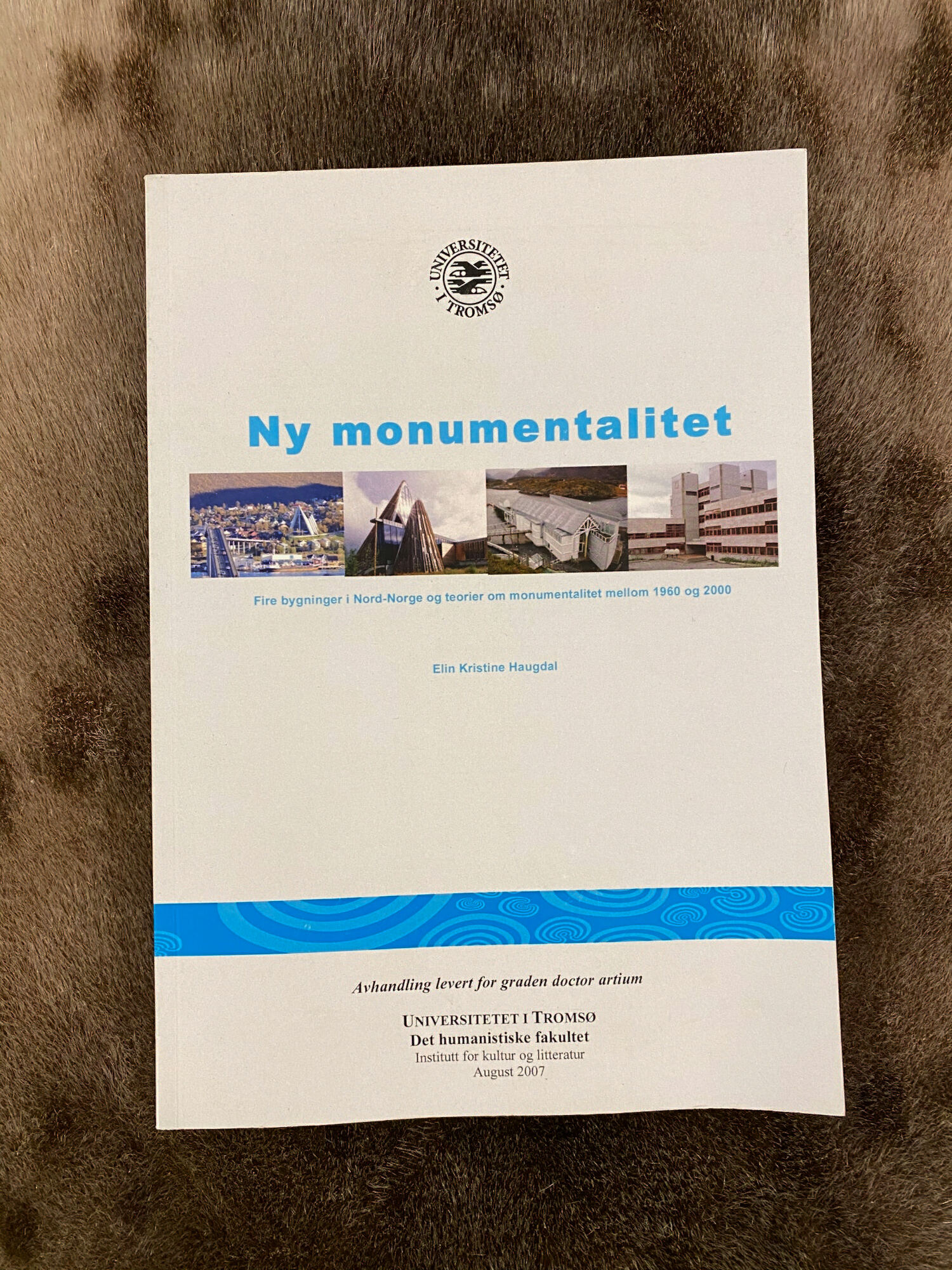

"The Sámi Parliament may be regarded as one of the most important singular buildings in Sápmi.

Elin Haugdal: Strategies of Monumentality in Contemporary Sámi Architecture,

As an institution and as a type, the parliament belongs to a group of buildings, public buildings, that we usually categorise as monumental. However, in an architectural sense, this building’s monumentality is of greater uncertainty and could be described as ‘weak monumentality’. The term ‘weak’ refers to the Italian philosopher Gianni Vattimo, a follower of Hans-Georg Gadamer, and his essays ‘Ornament/Monument’, published in 1985, and ‘Postmodernity and new monumentality’, printed ten years later. Vattimo elaborates on how art and architecture can serve as a model for thinking. This kind of thinking does not aim at ‘strong thought’, such as, for instance, the hard sciences or political realism. Vattimo instead gives value to ‘weak thought’,

pensiere debole. Weak thought, he says, is characterised by a re-thinking of given and dominating values and truths which open up a space for the marginalised and suppressed. This can be transferred to the political and cultural discourse surrounding the creation of the first parliament building in Sápmi, which is an important symbol for the Sámi population specifically, Norwegian society in general, and to all indigenous populations on a global level."

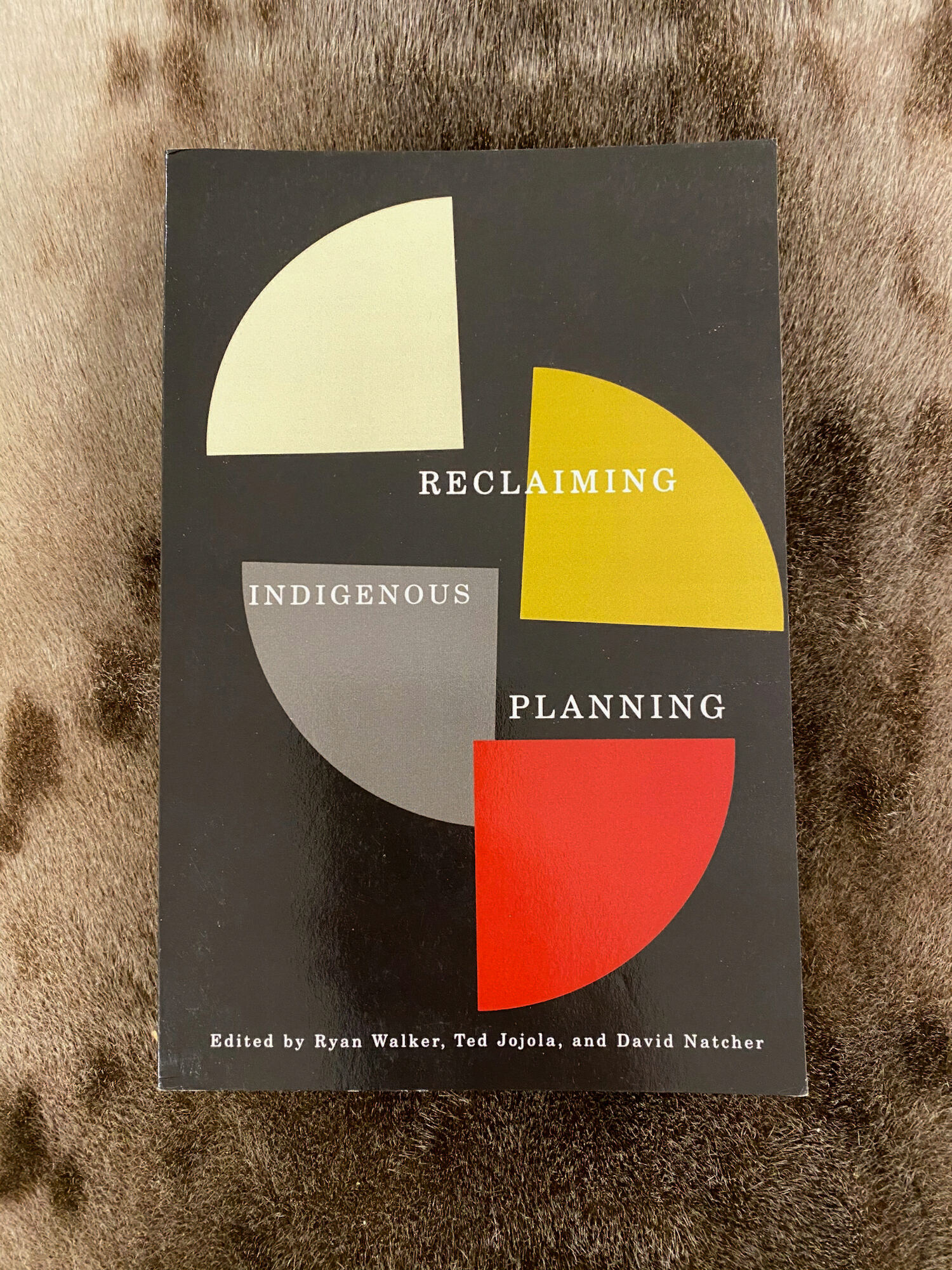

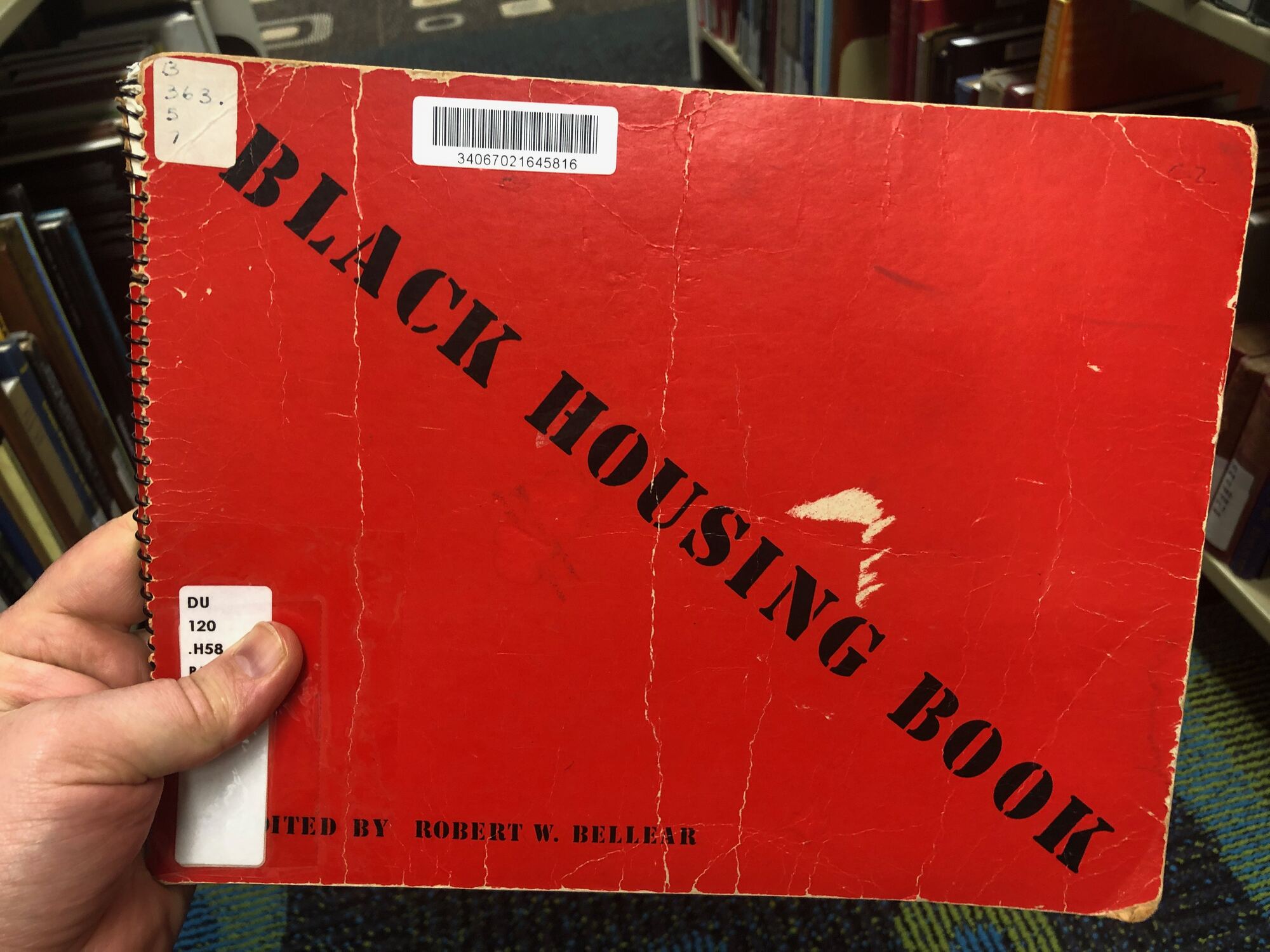

"The cultural design paradigm involves the use of models of culturally distinct behaviour to inform definitions of Aboriginal housing needs. Its premise is that to competently design appropriate residential accommodation for Aboriginal people who have traditionally oriented lifestyles, architects must understand the nature of those lifestyles, particularly in the domiciliary context."

Paul Memmott: TAKE 2 : Housing Design in Indigenous Australia, 2003

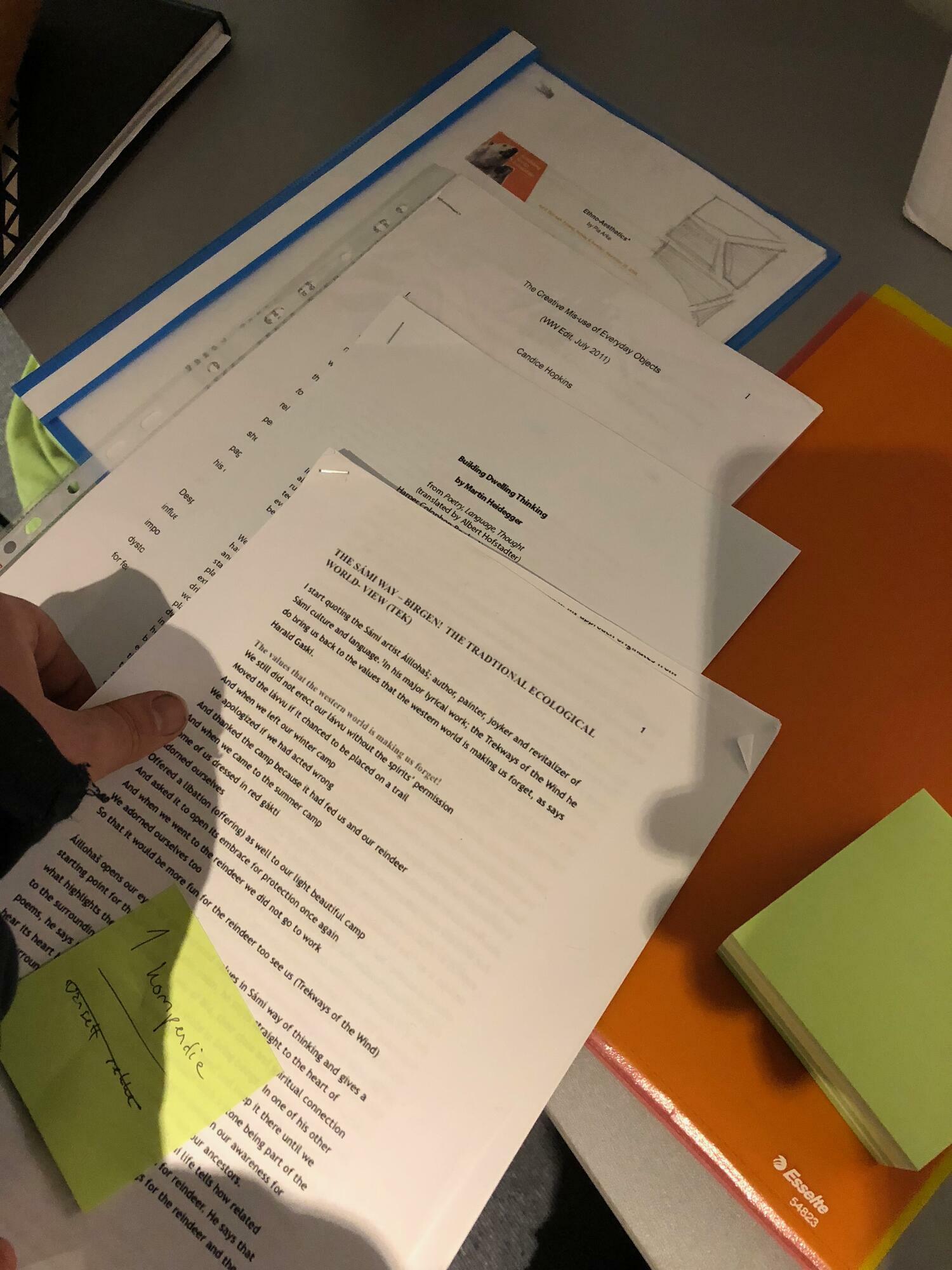

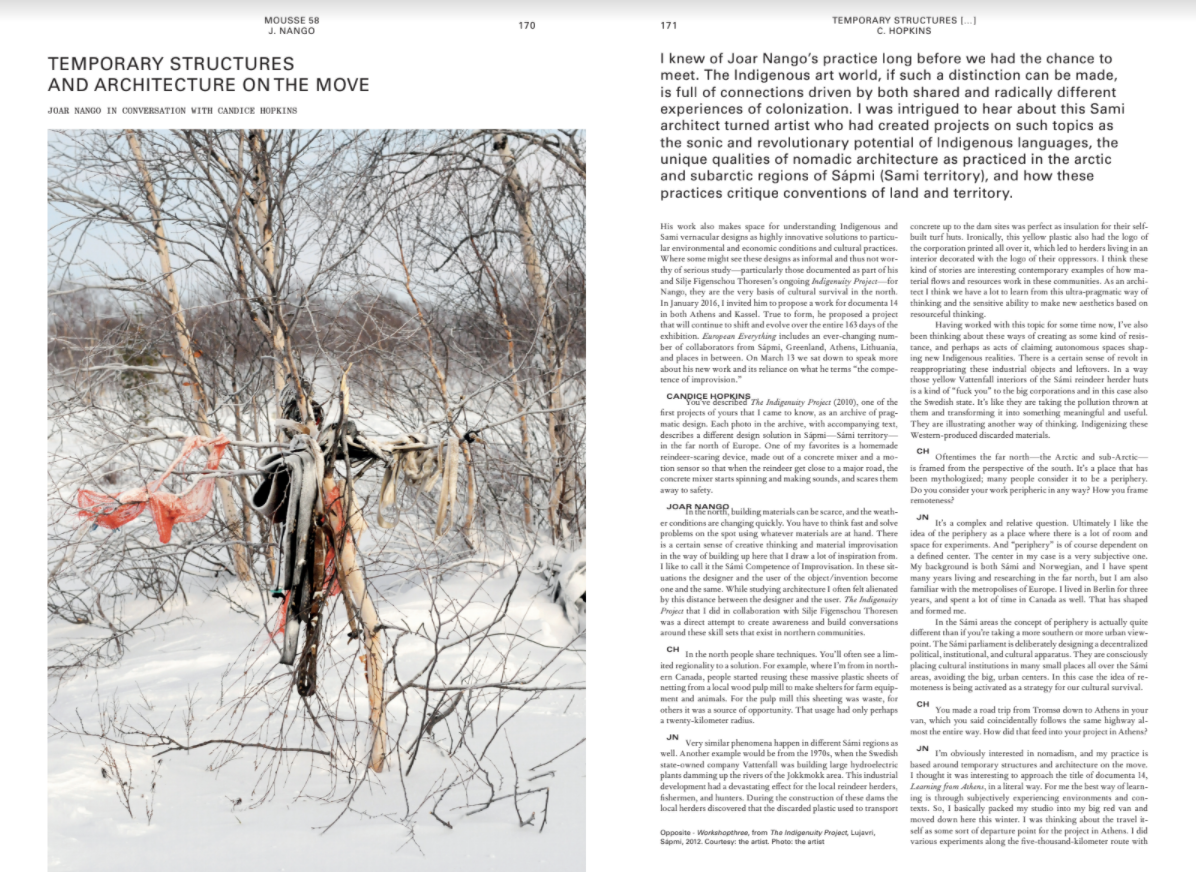

“I knew of Joar Nango’s practice long before we had the chance to meet. The Indigenous art world, if such a distinction can be made, is full of connections driven by both shared and radically different experiences of colonization. I was intrigued to hear about this Sami architect turned artist who had created projects on such topics as the sonic and revolutionary potential of Indigenous languages, the unique qualities of nomadic architecture as practiced in the arctic and subarctic regions of Sápmi (Sami territory), and how these practices critique conventions of land and territory.”

JOAR NANGO IN CONVERSATION WITH CANDICE HOPKINS: MOUSSE MAGAZINE 58, TEMPORARY STRUCTURES AND ARCHITECTURE ON THE MOVE, April-May 2017

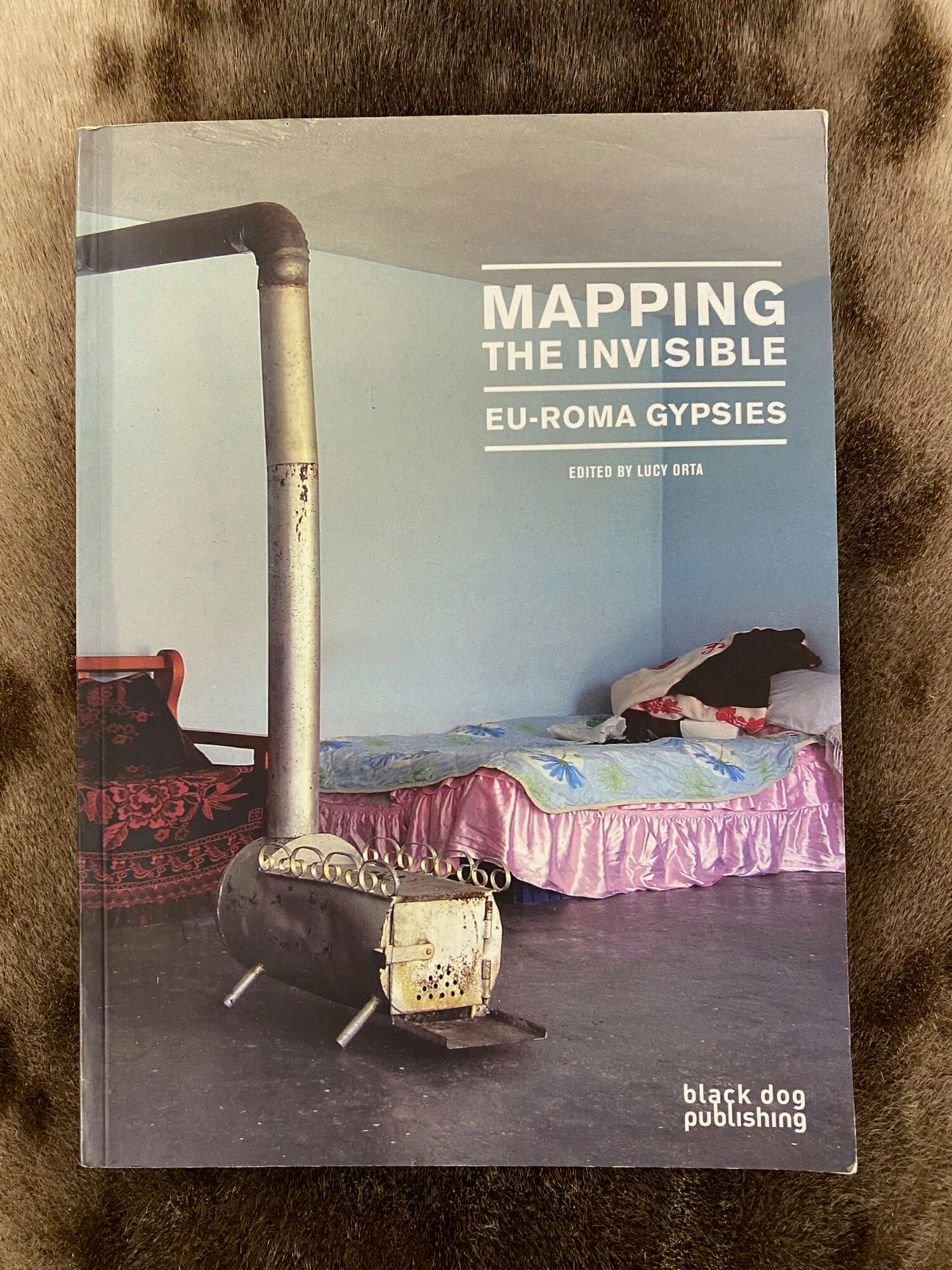

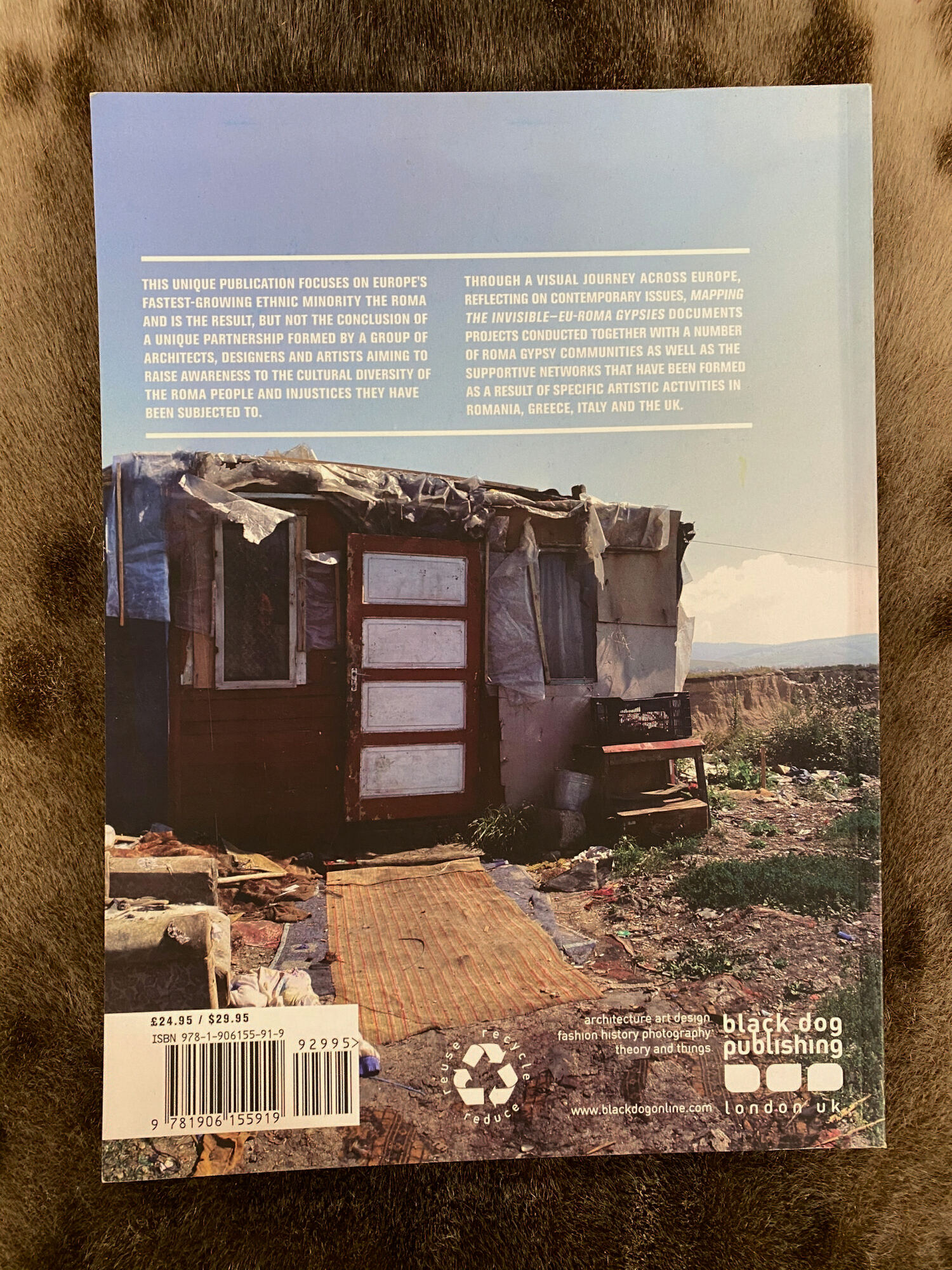

“I’ve been asking myself what lies in the shadowy or invisible parts of Europe. I want to make new intercultural connections. I am thinking about the future. What happens when a new Indigenous feminist union establishes itself? How will such a thing look, and what can it possibly offer us?”

JOAR NANGO IN CONVERSATION WITH CANDICE HOPKINS: MOUSSE MAGAZINE 58: TEMPORARY STRUCTURES AND ARCHITECTURE ON THE MOVE, April-May 2017

“Our European Union is falling apart. Europe is not falling apart; Europe will remain on its continent, and it’s built of so many more complex sizes, categories, cultures, and materials than the nation-state puzzle explains.”

JOAR NANGO IN CONVERSATION WITH CANDICE HOPKINS: MOUSSE MAGAZINE 58: TEMPORARY STRUCTURES AND ARCHITECTURE ON THE MOVE, April-May 2017

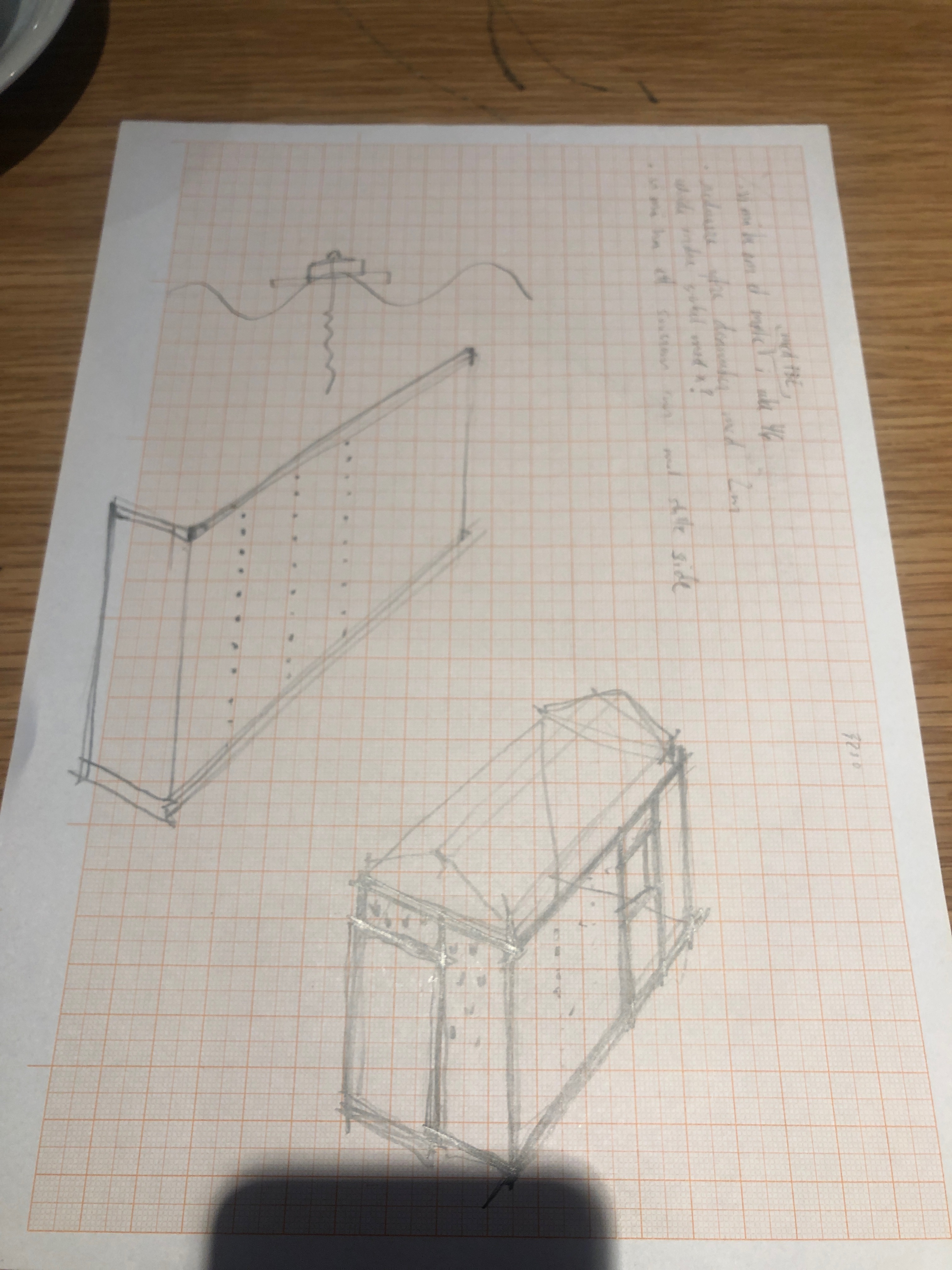

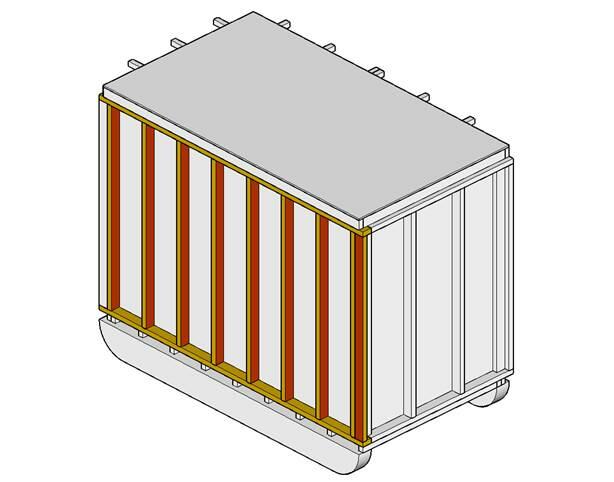

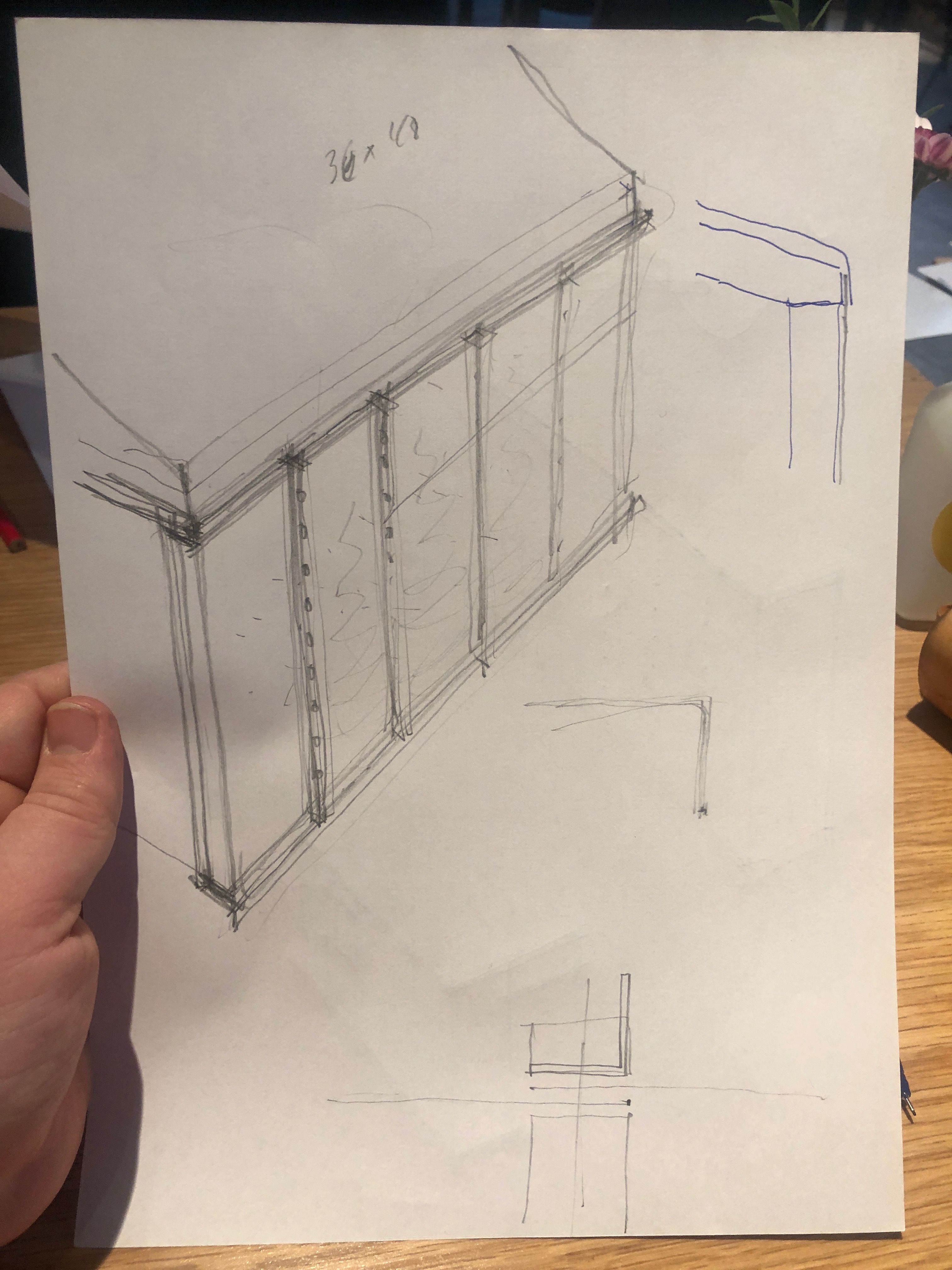

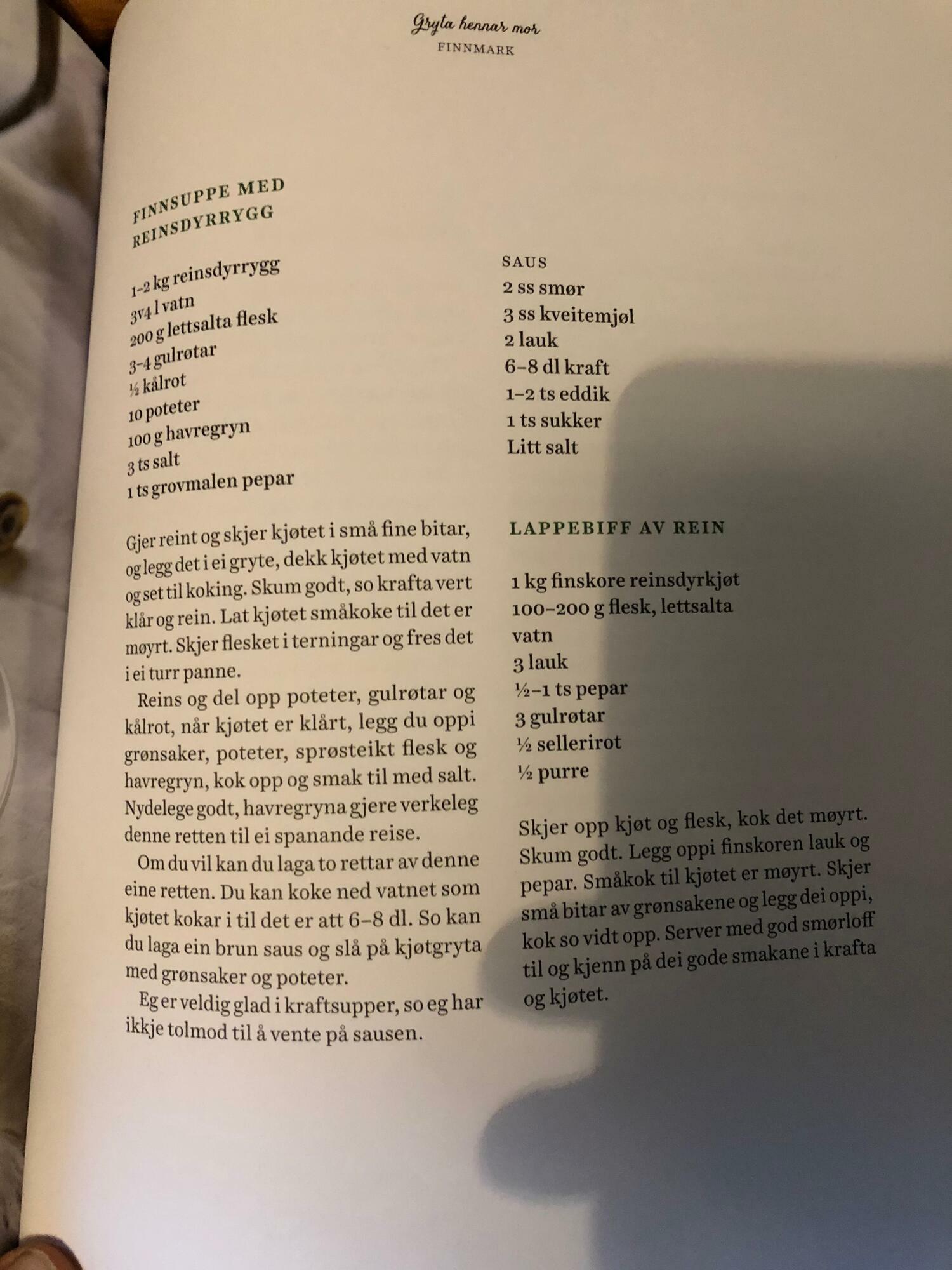

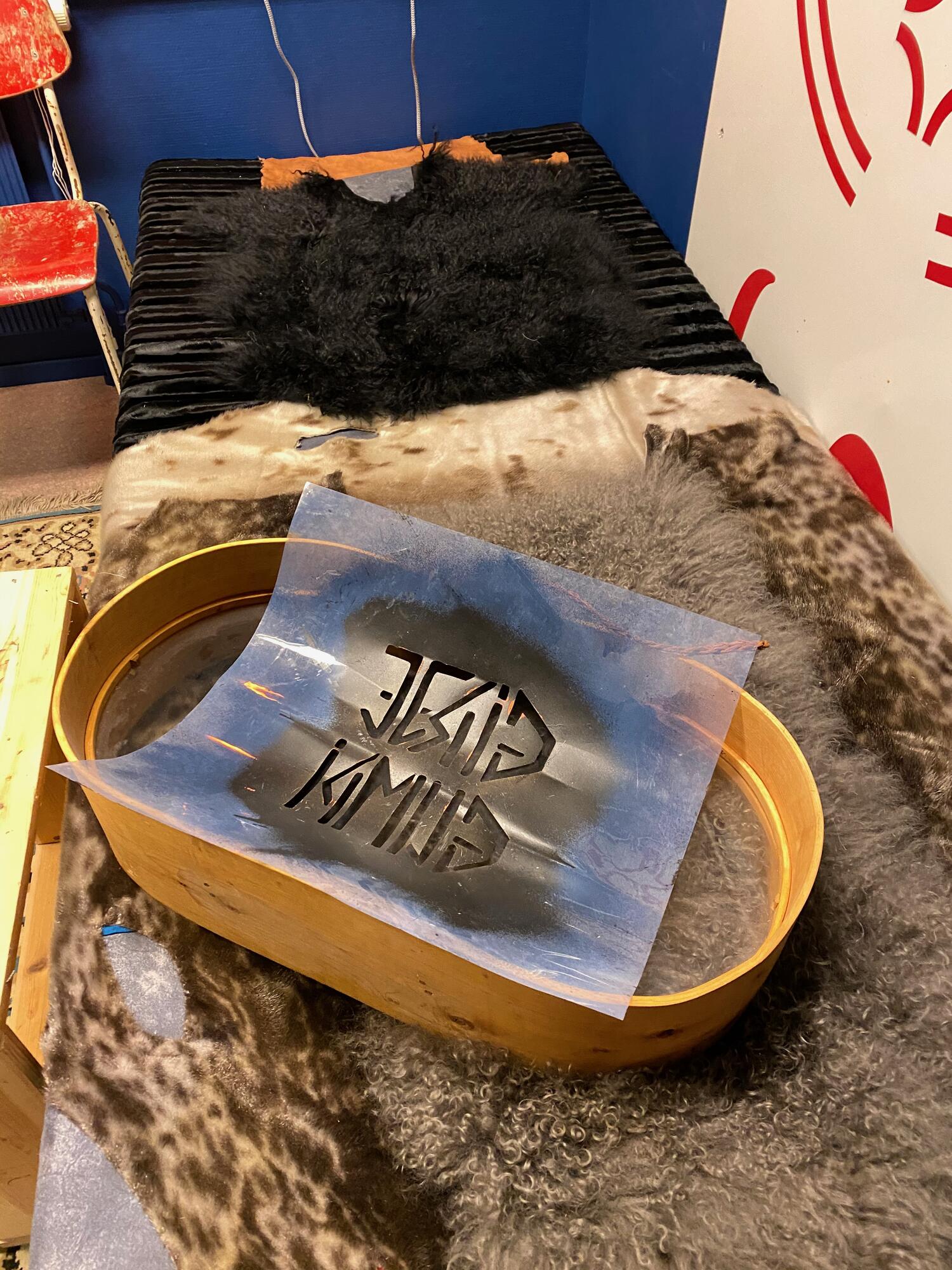

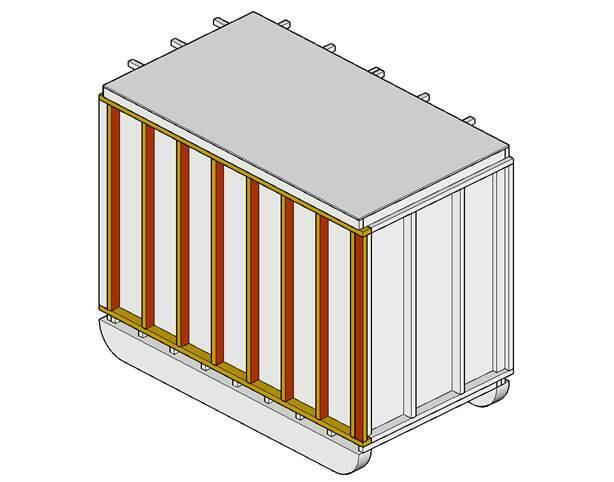

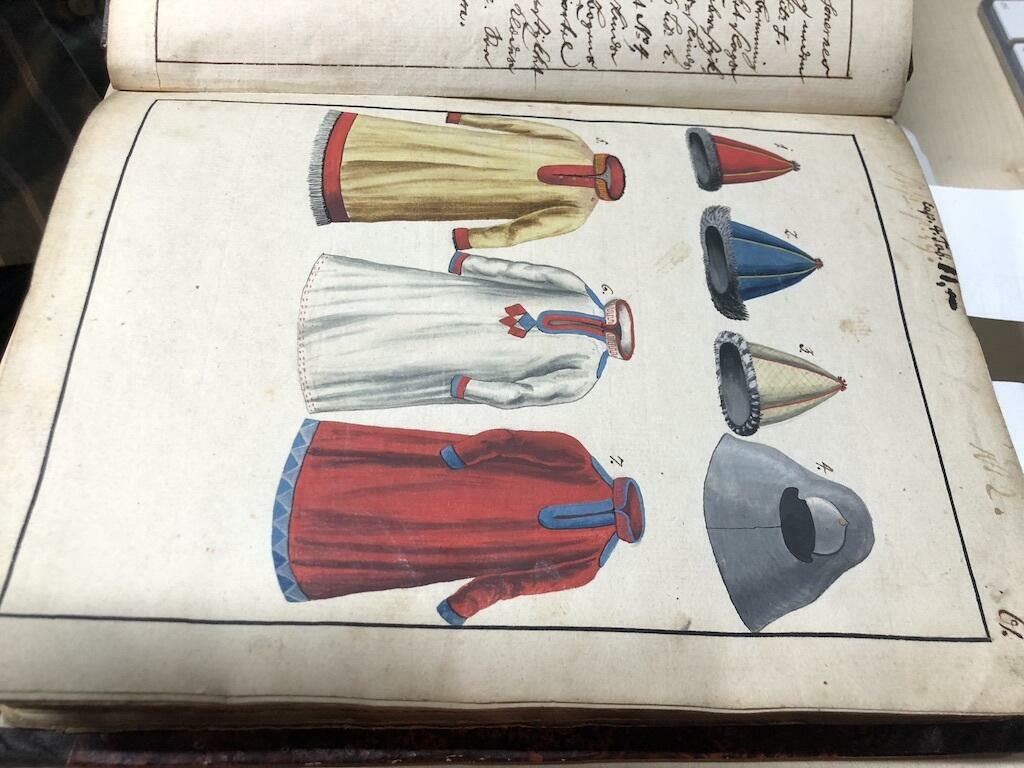

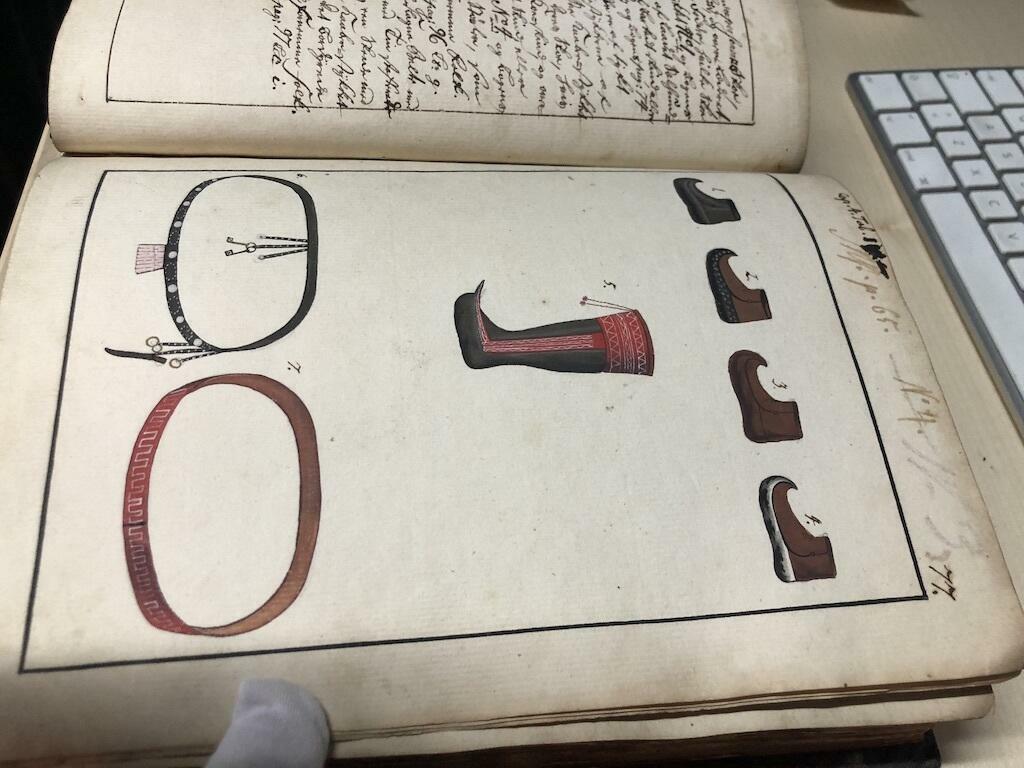

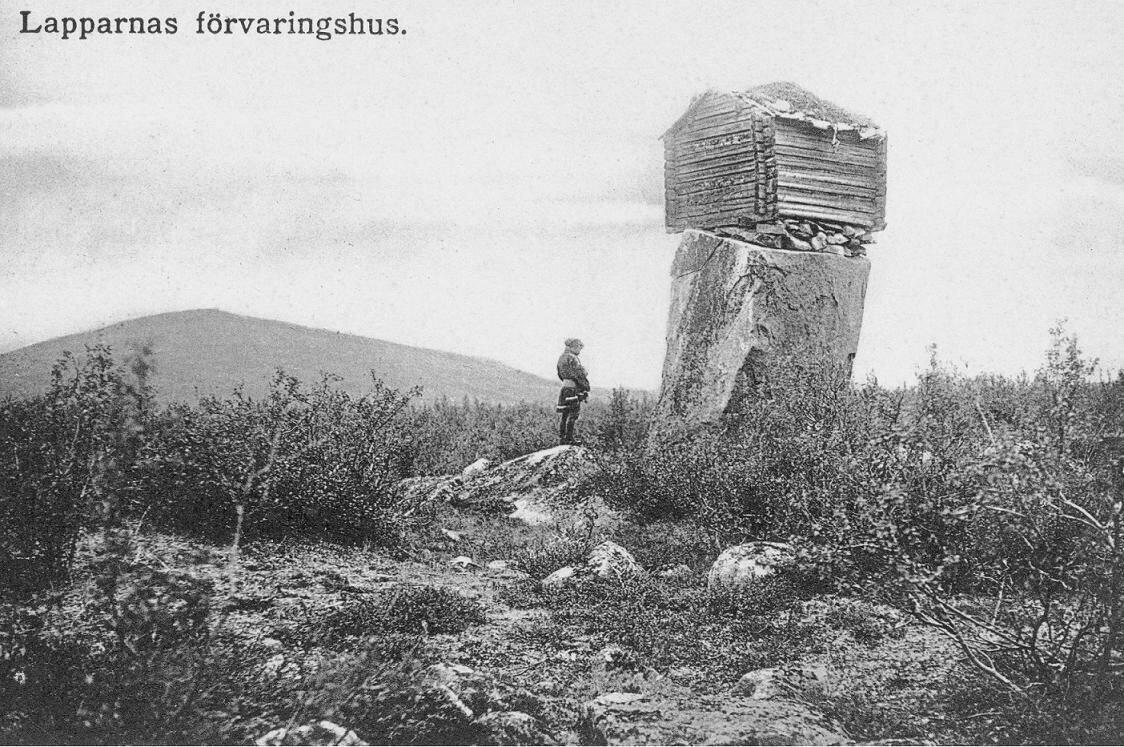

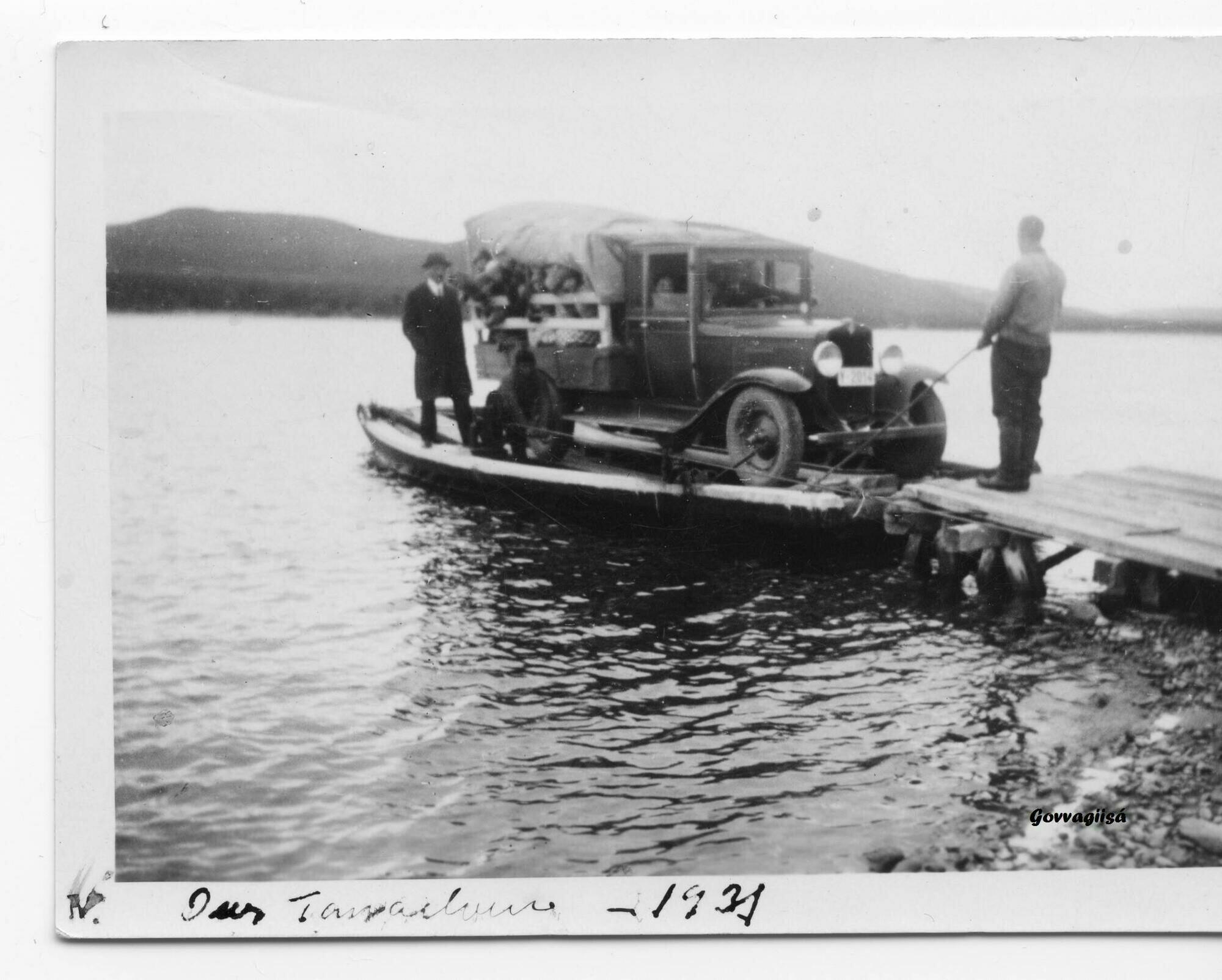

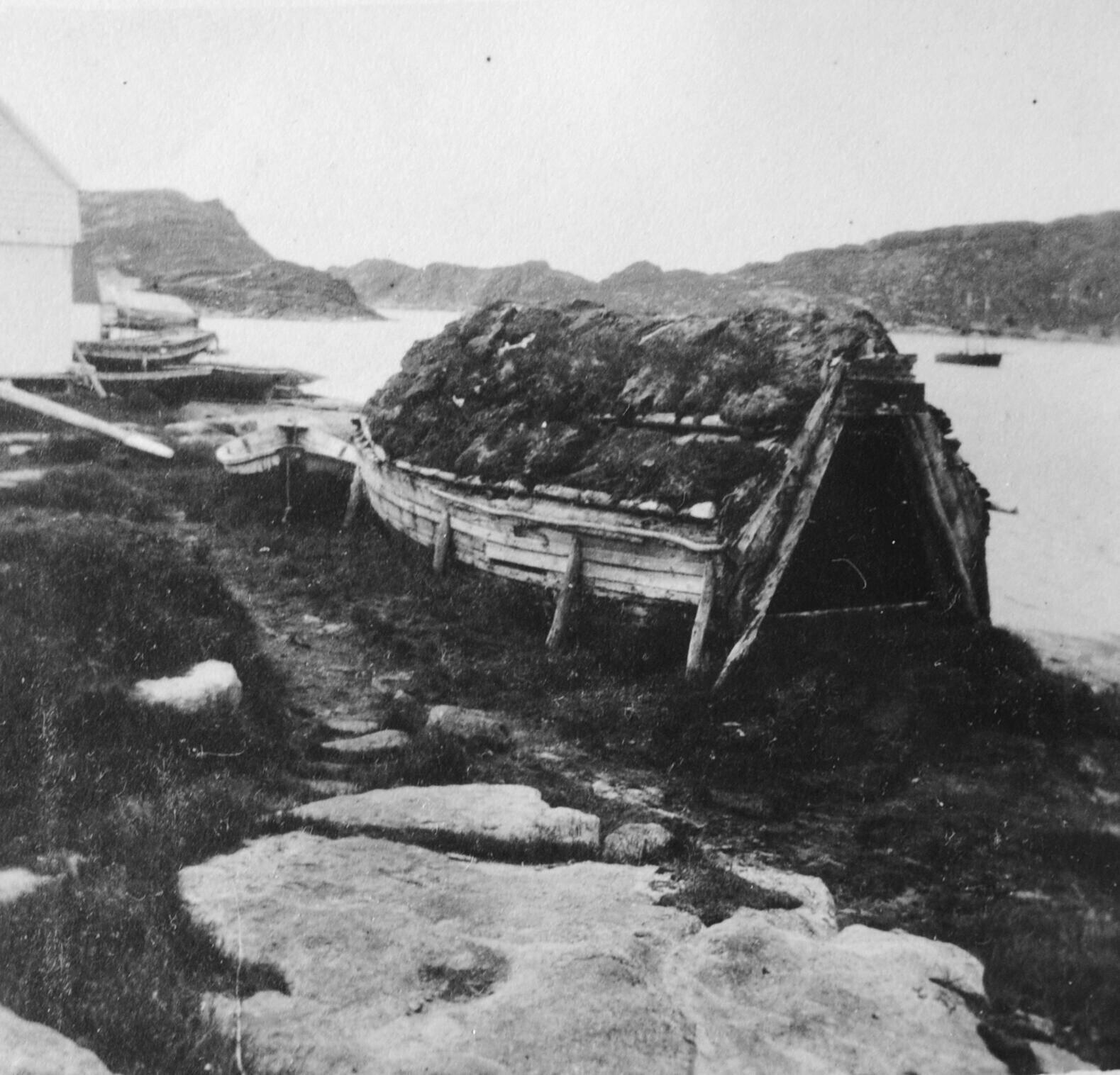

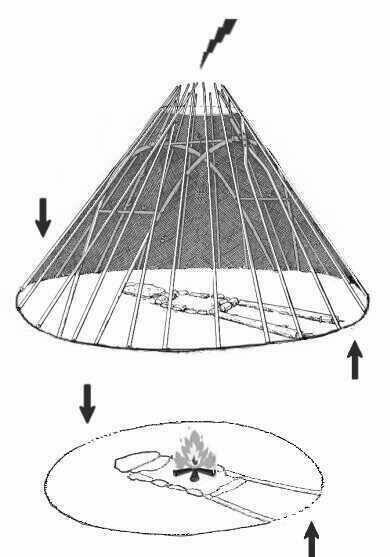

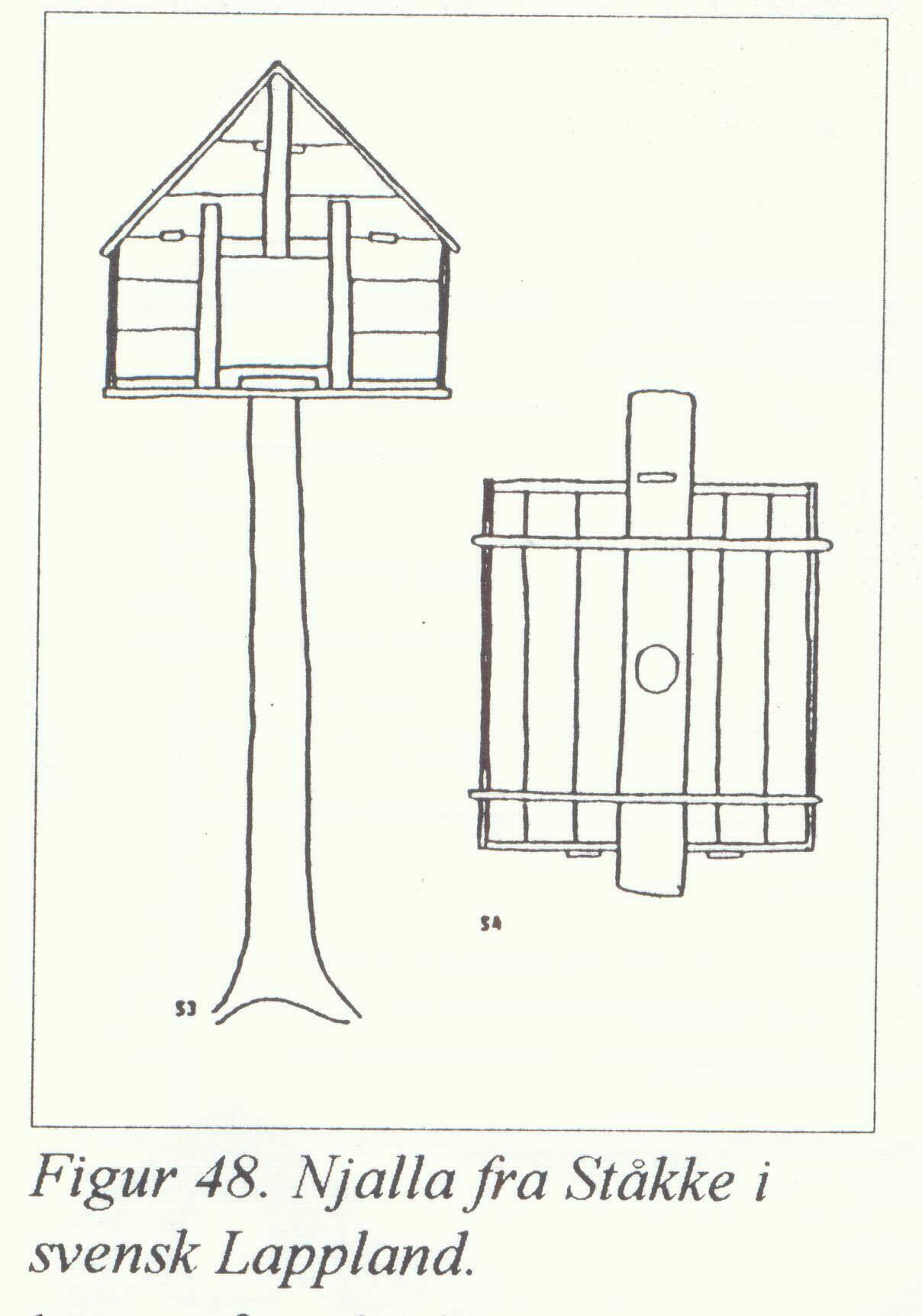

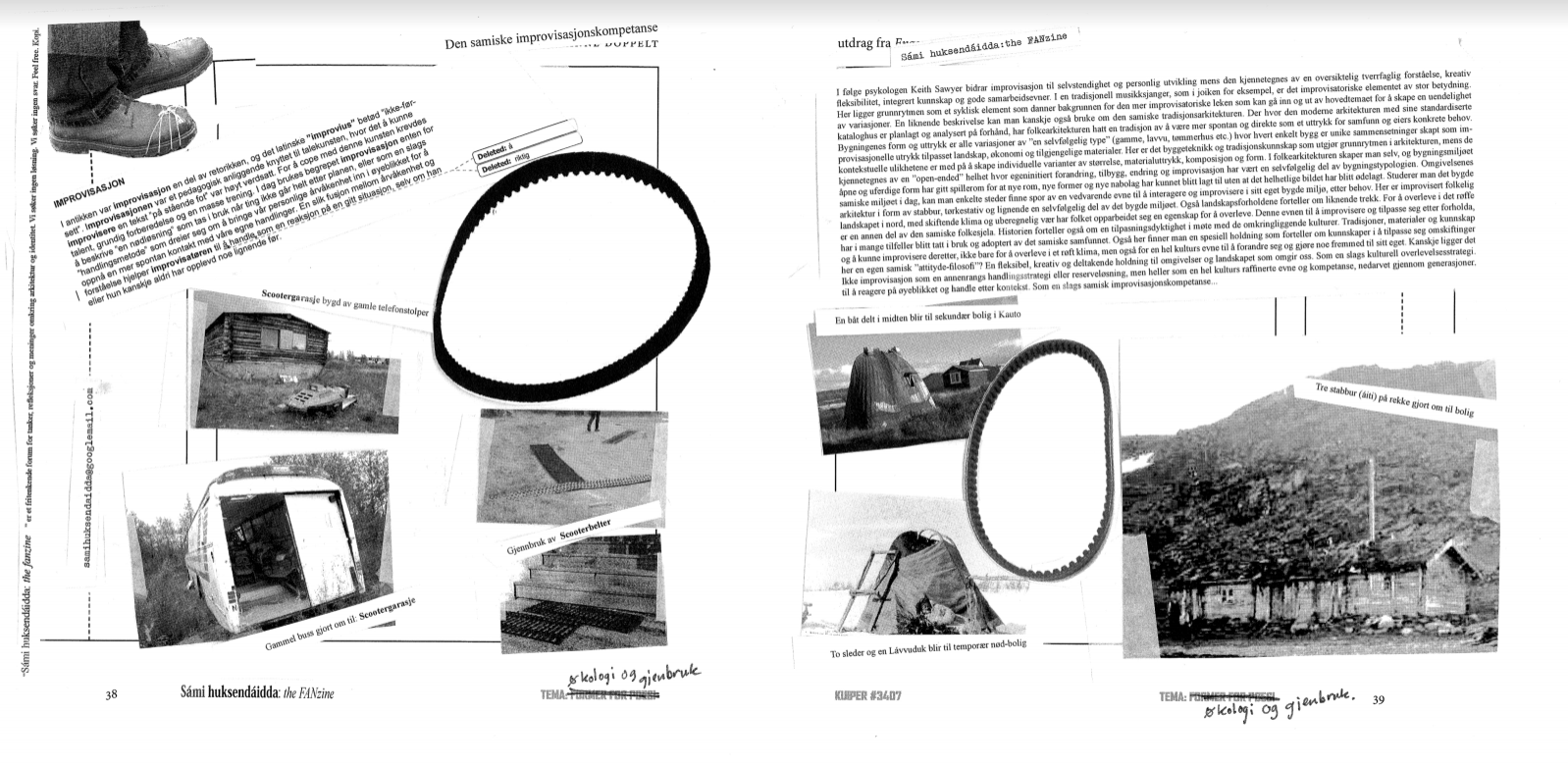

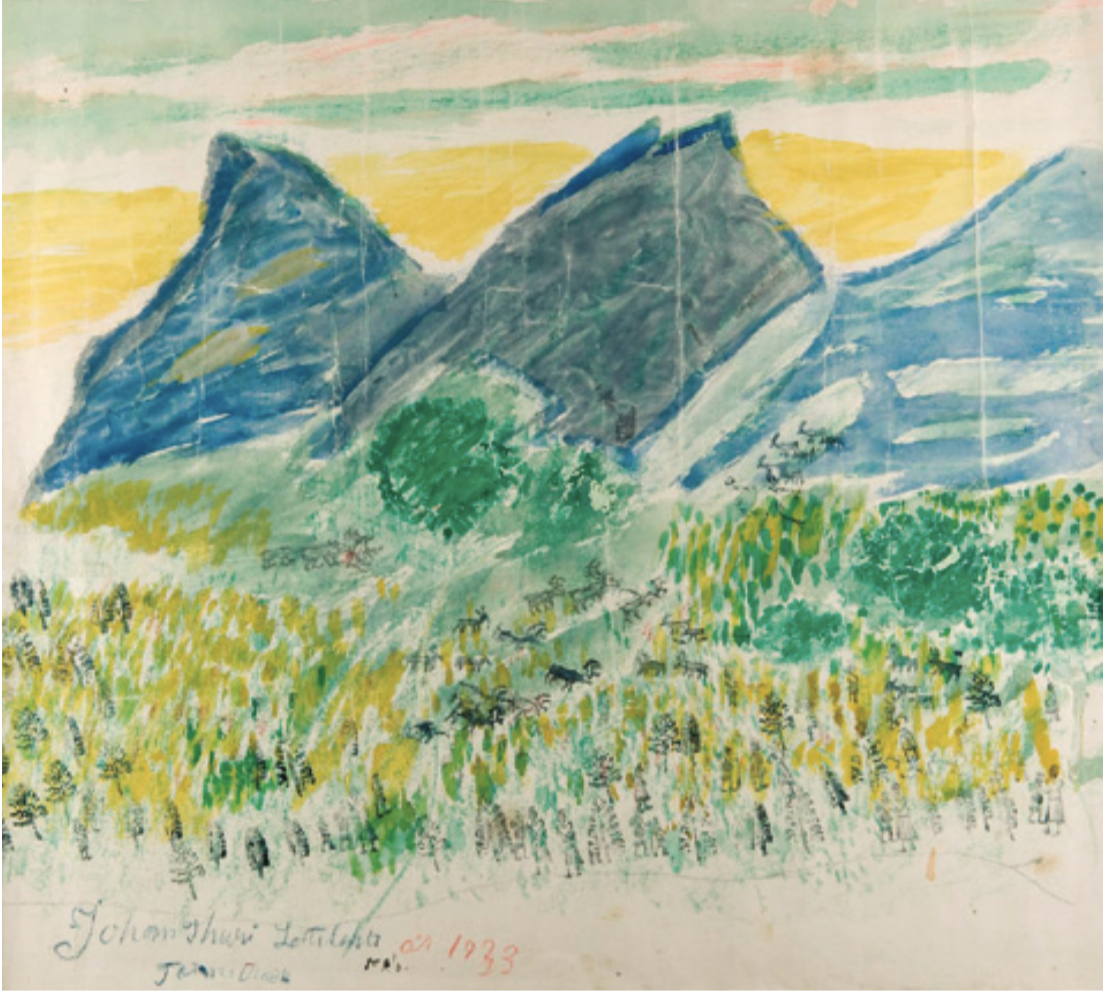

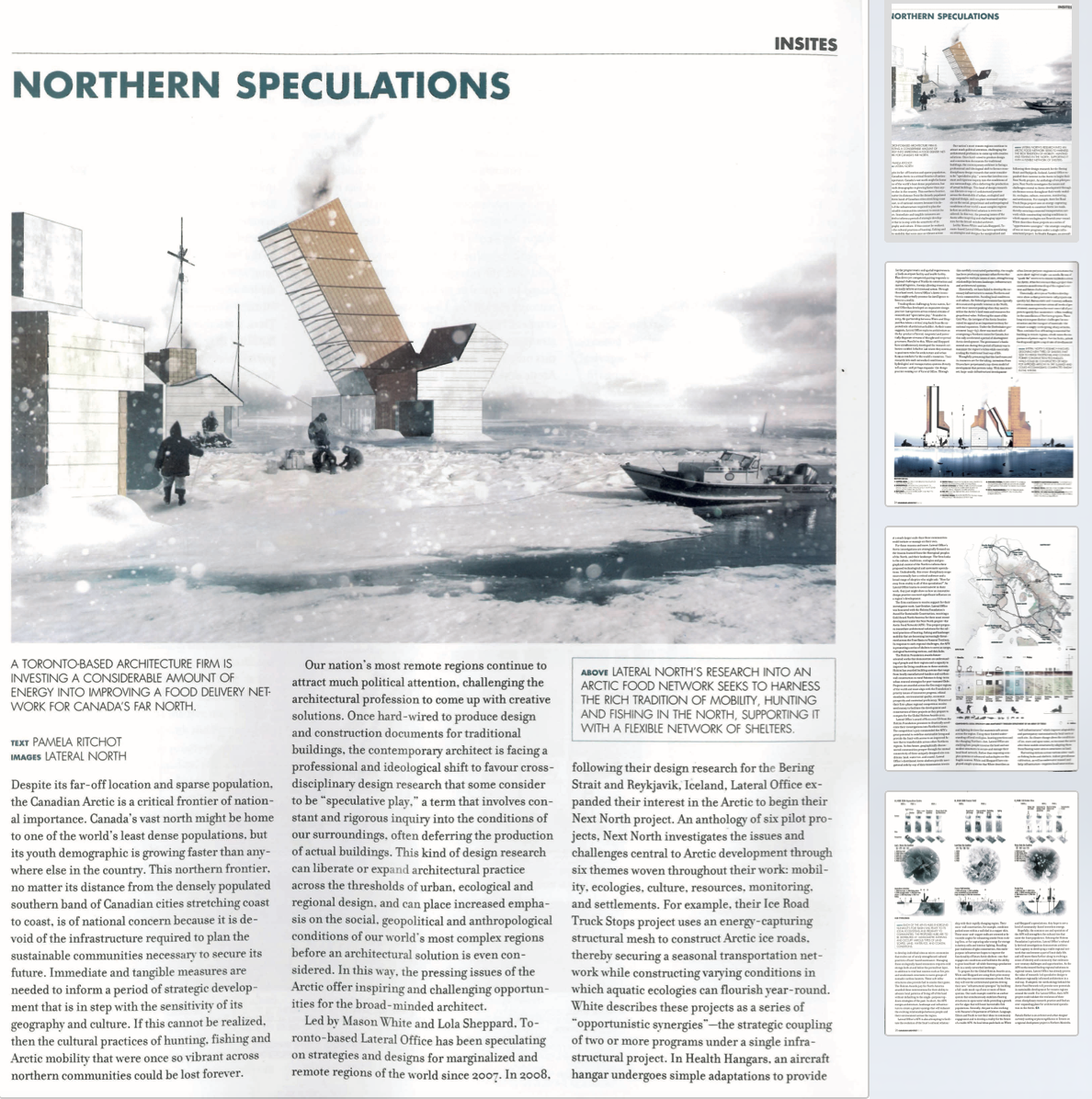

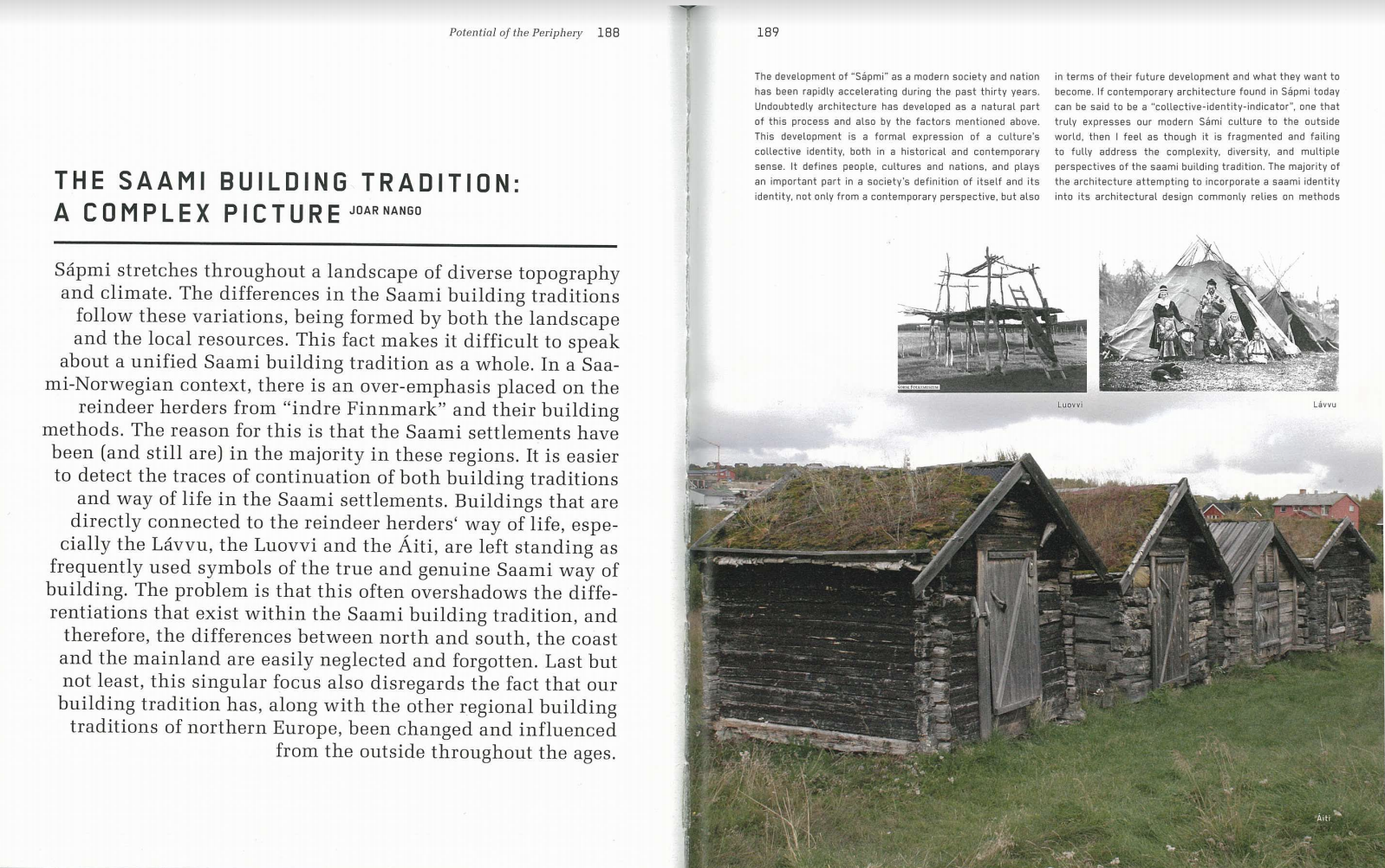

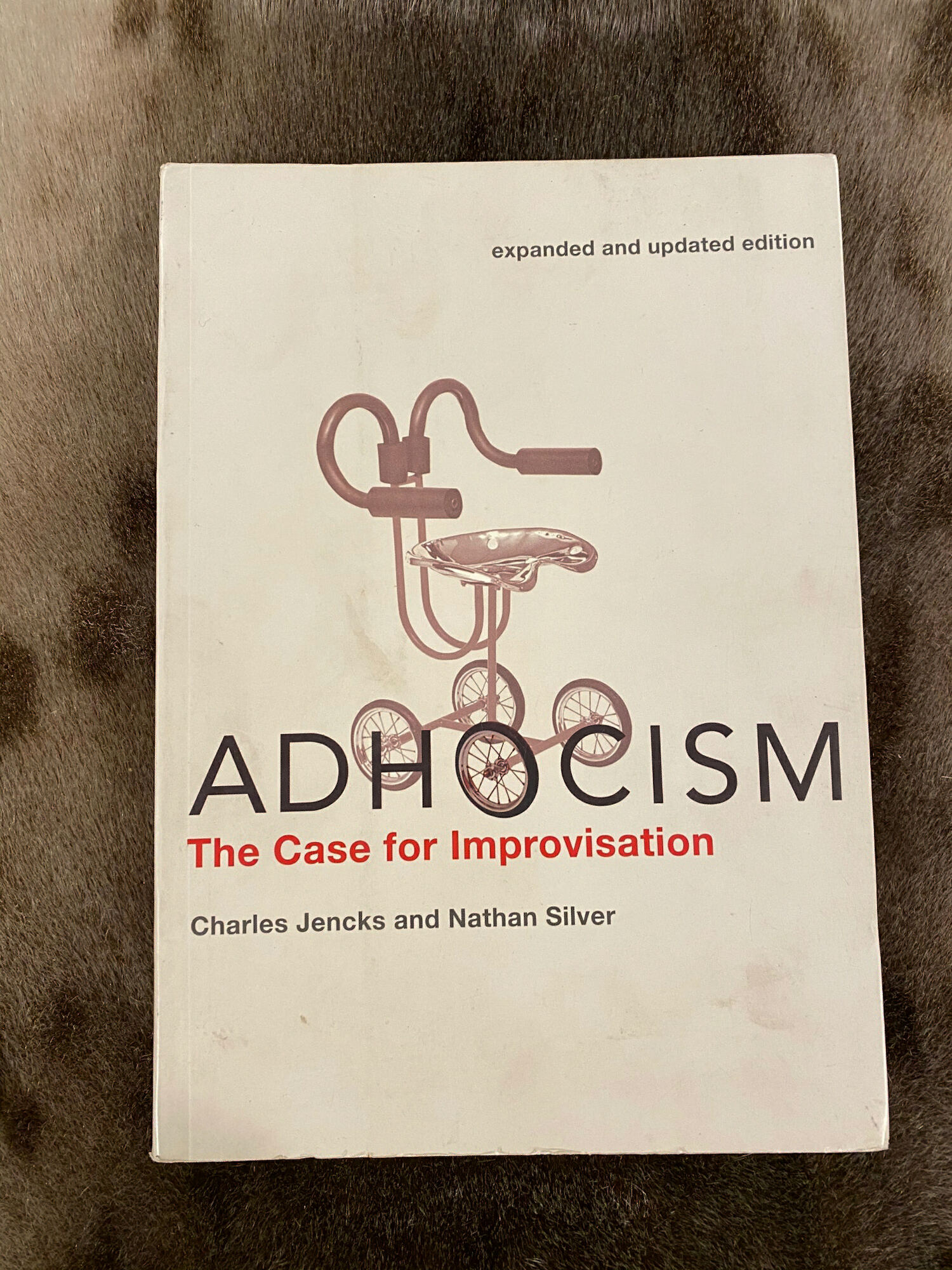

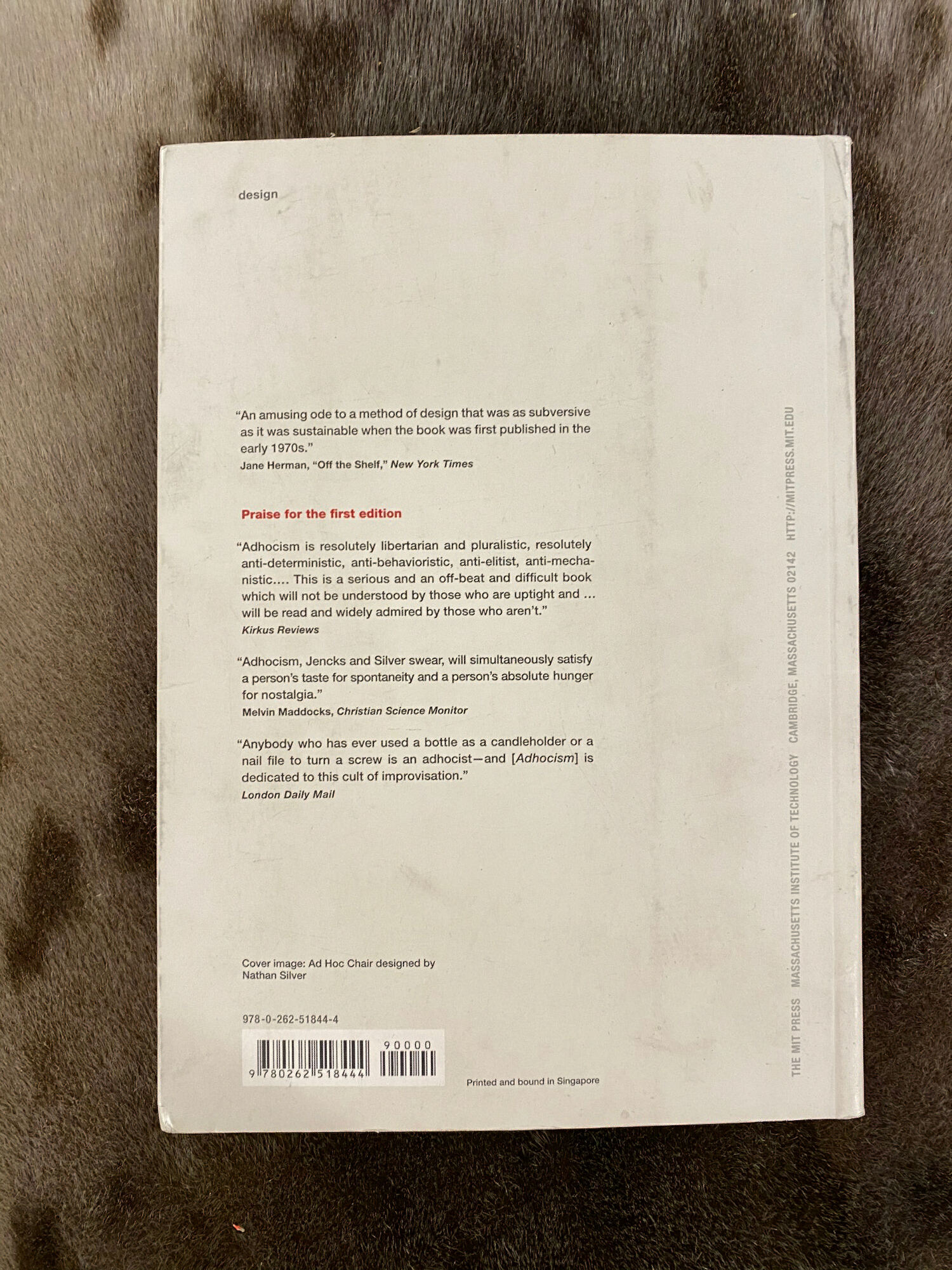

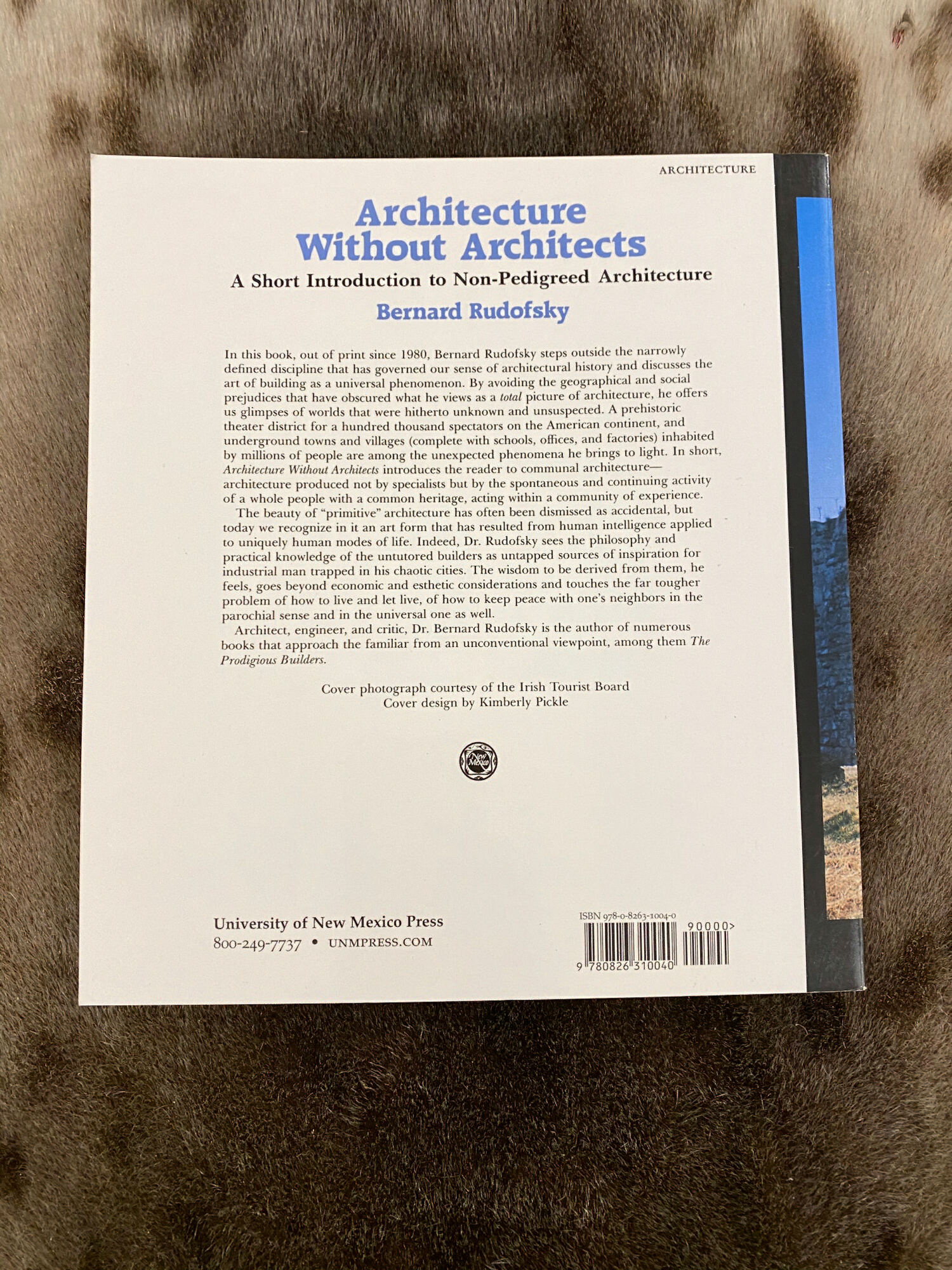

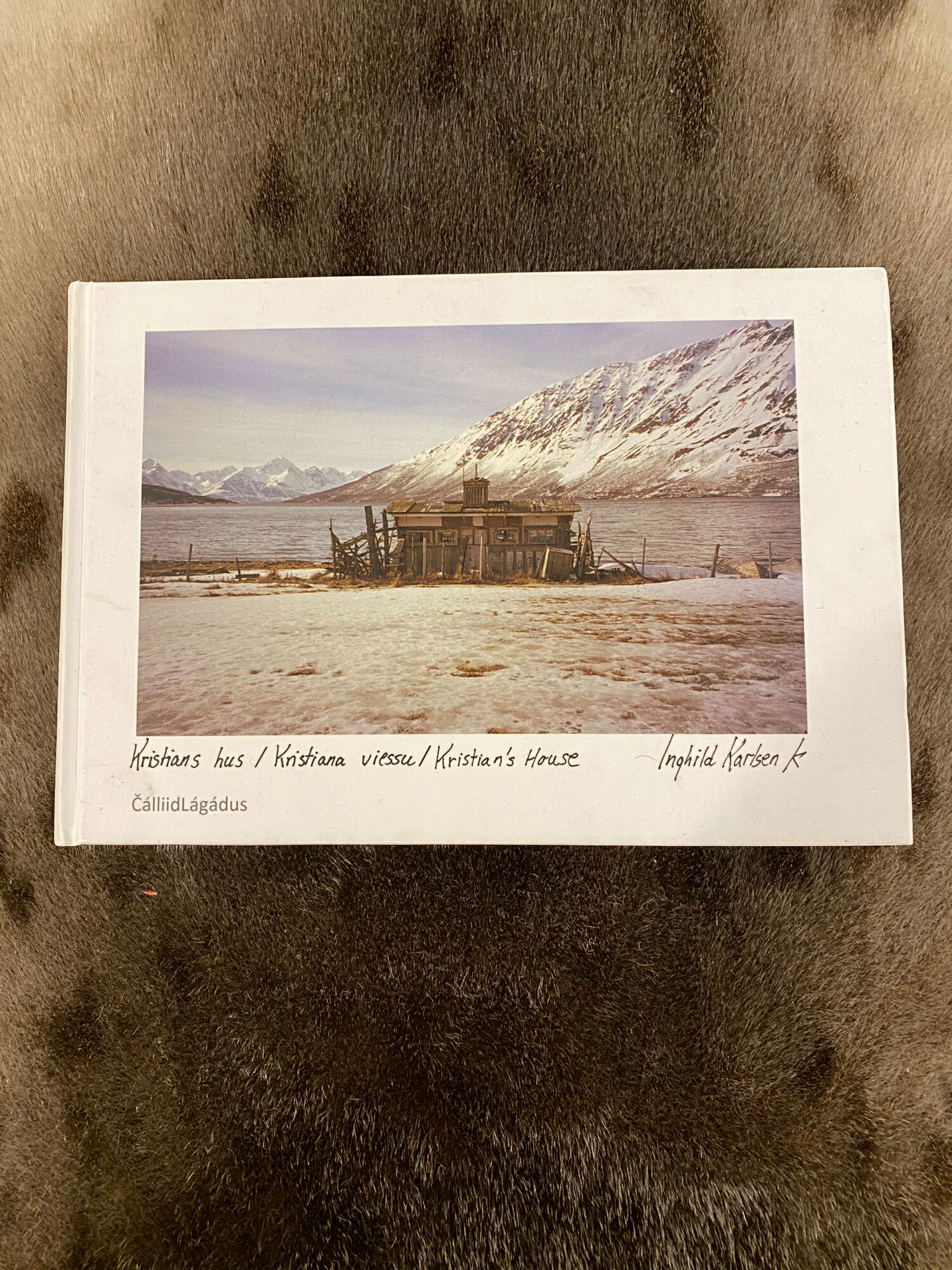

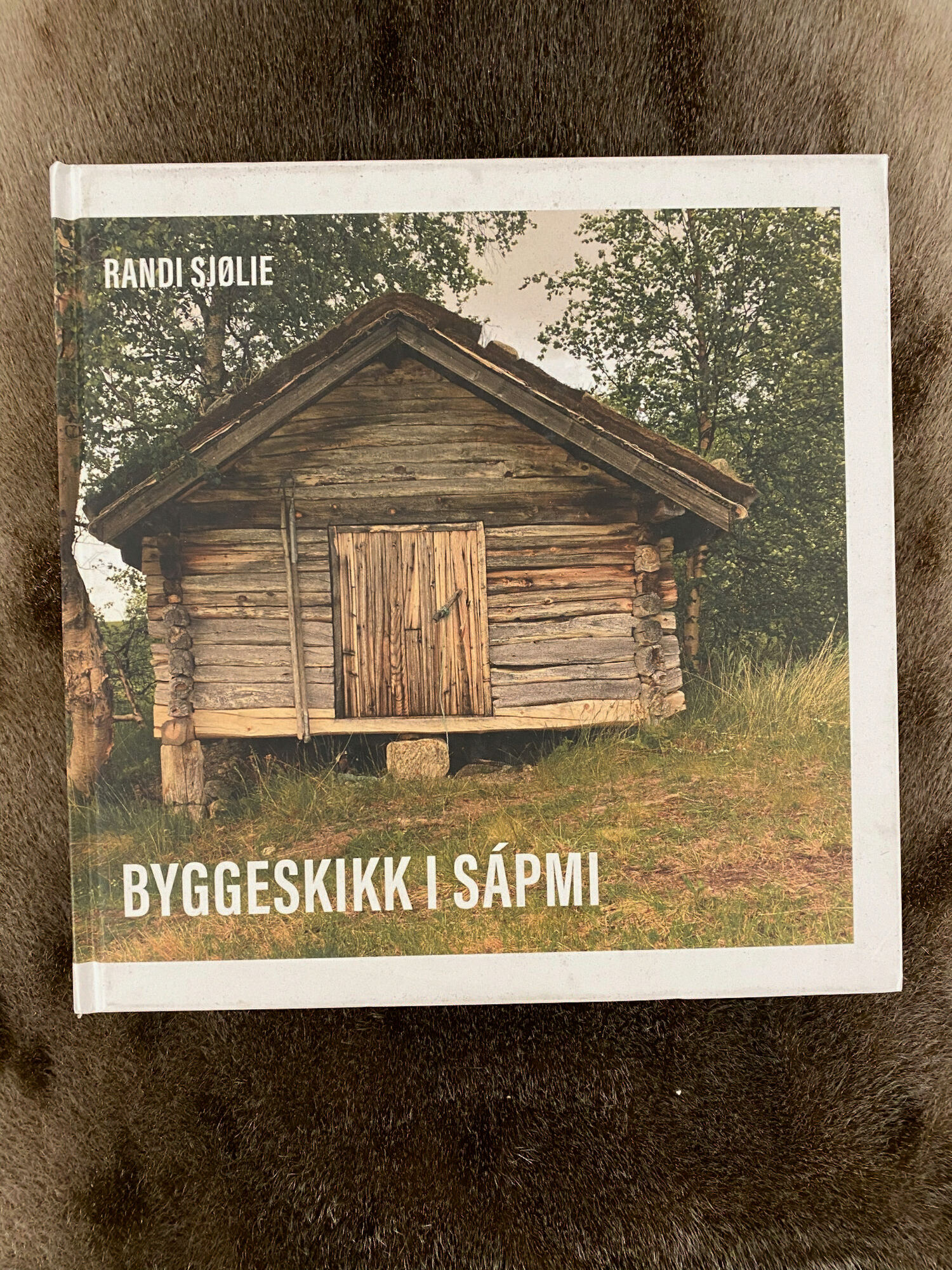

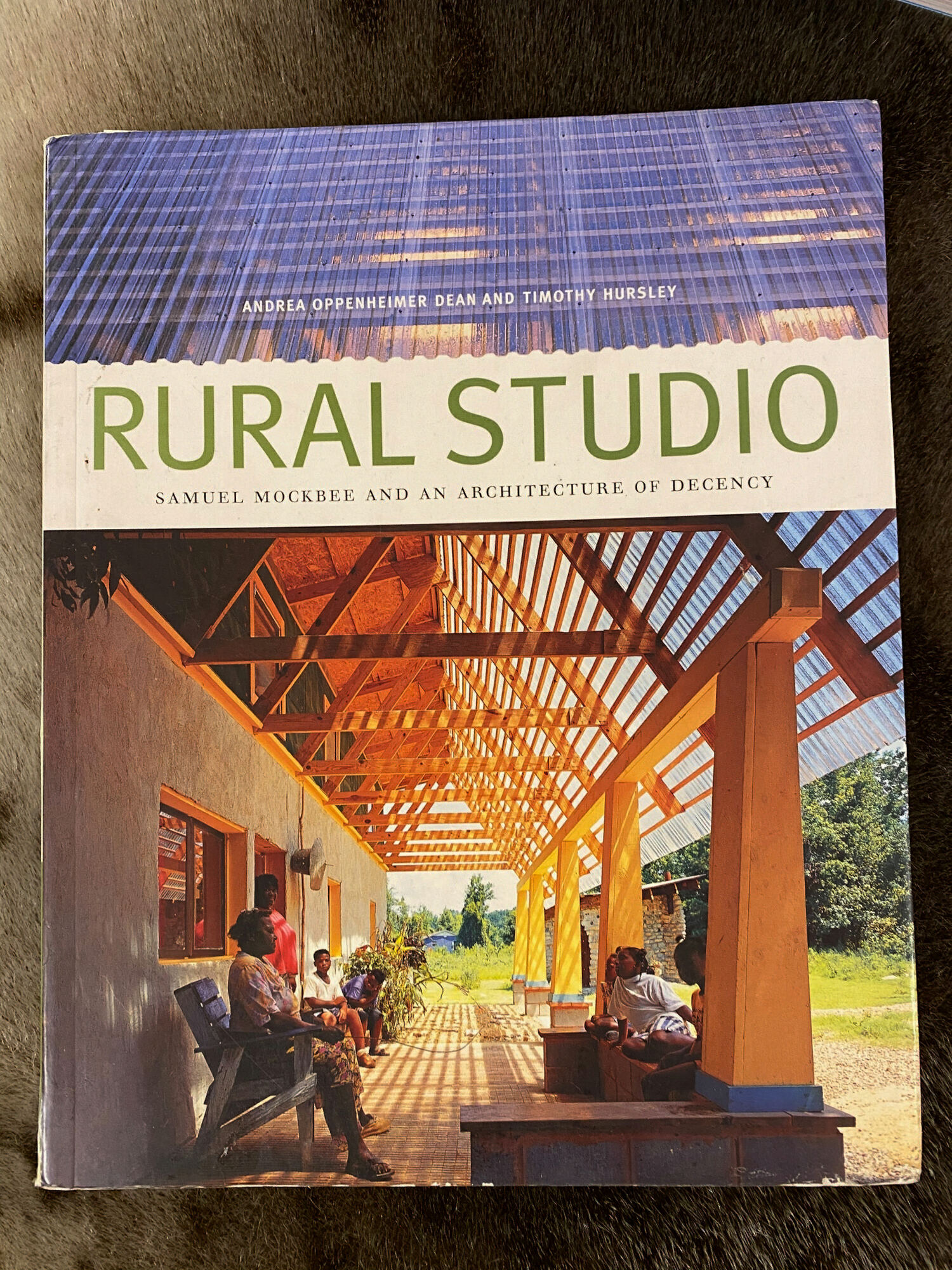

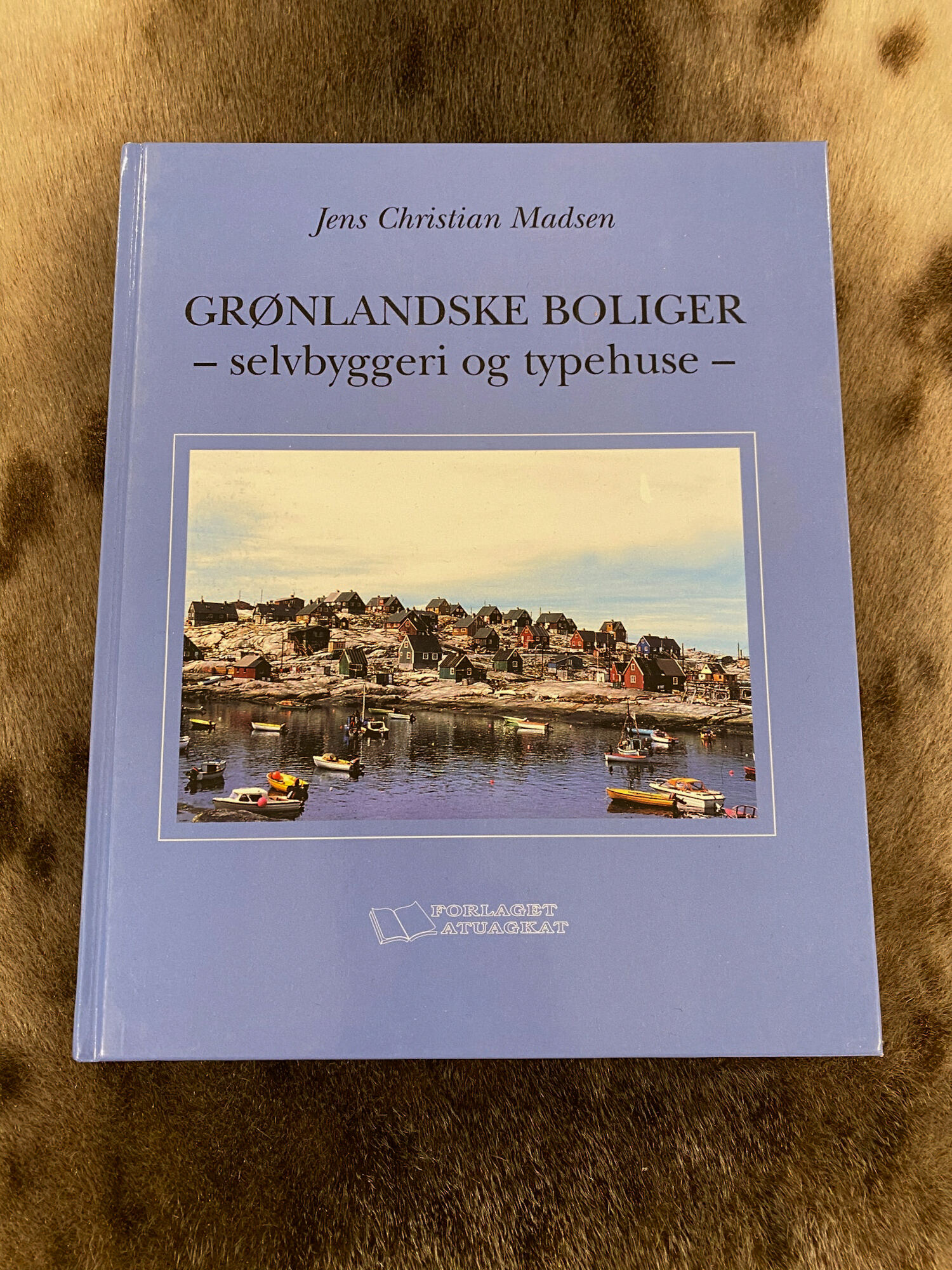

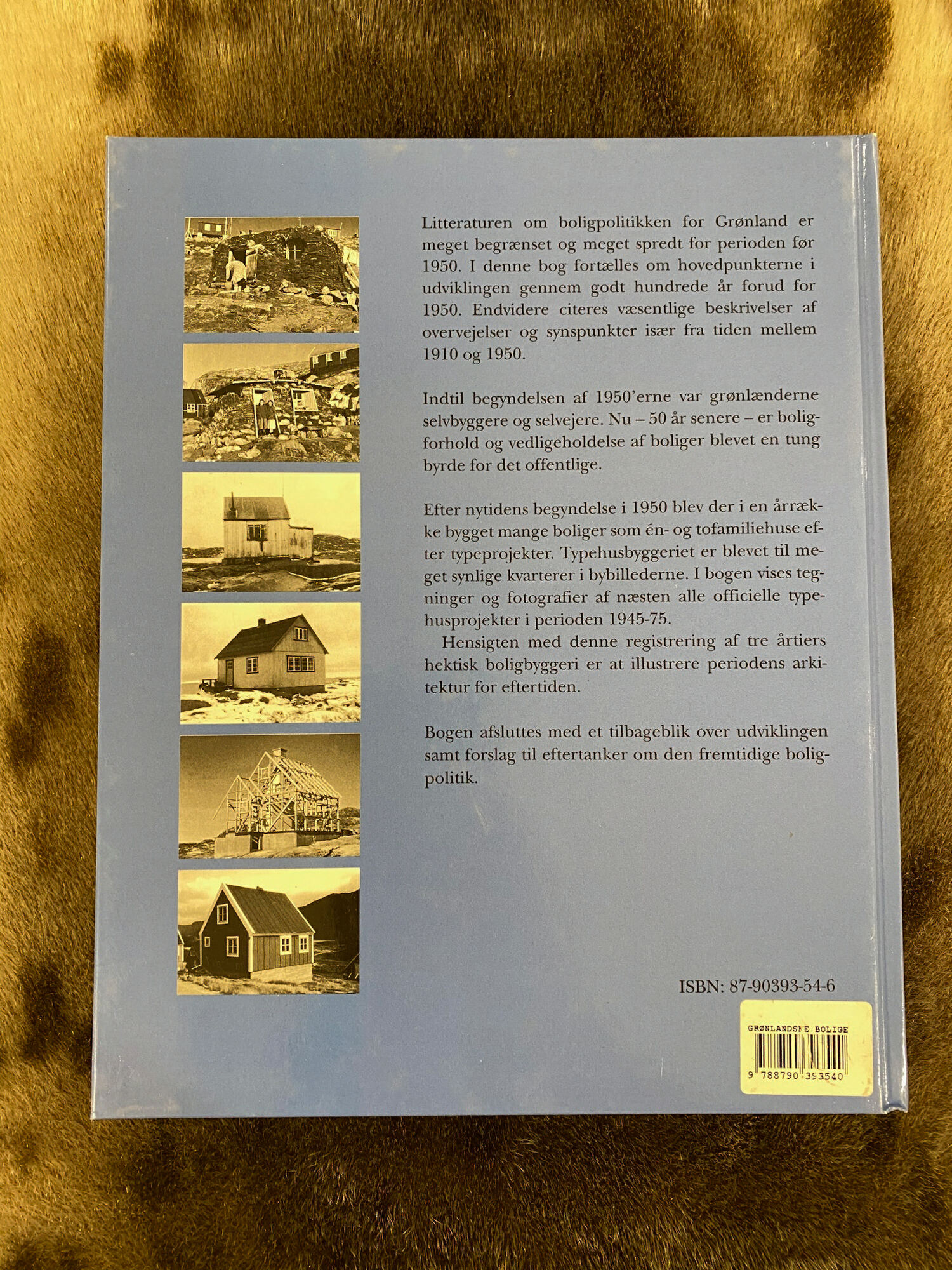

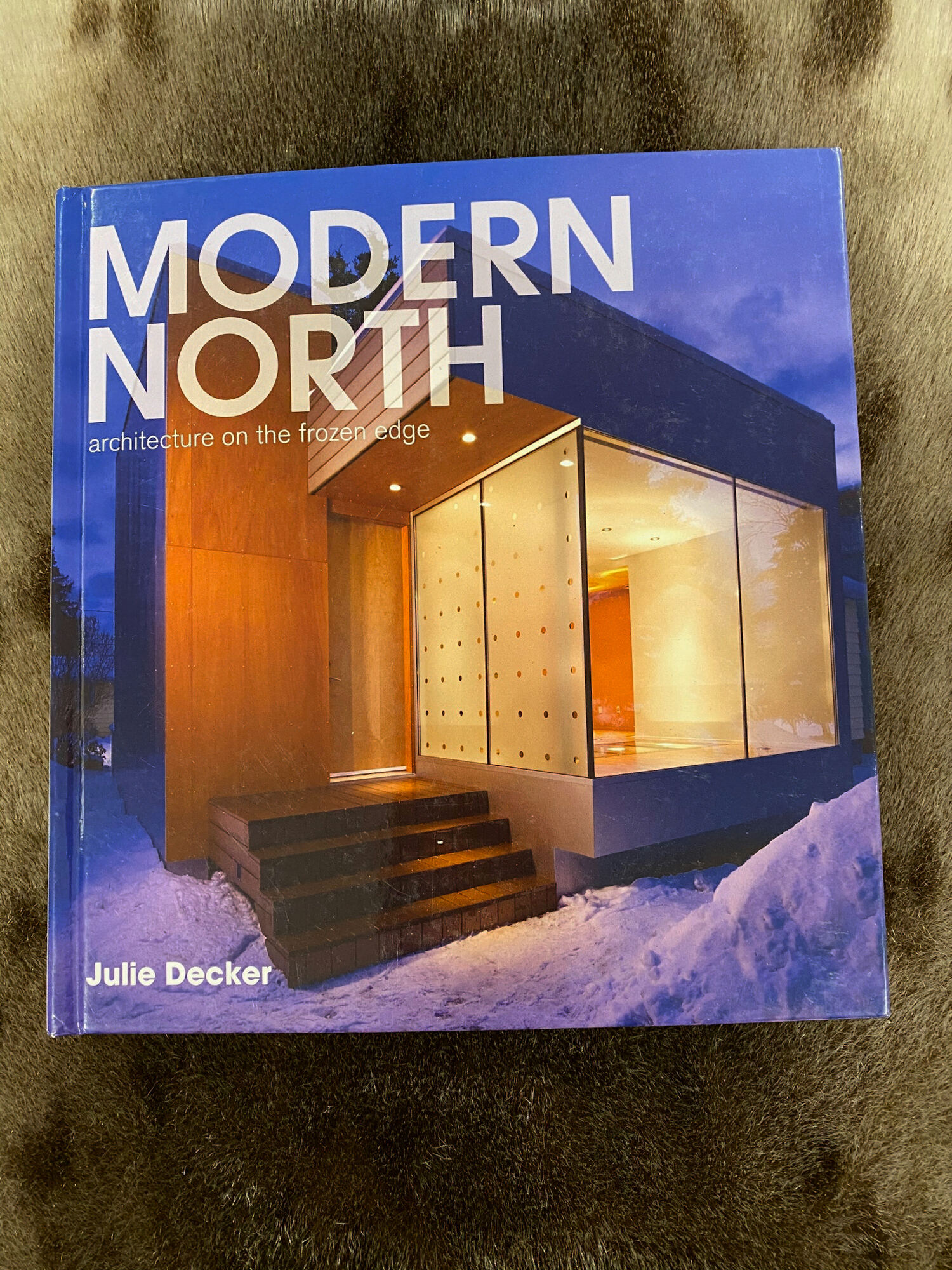

”A fruitful way of approaching this might be to understand the Saami building tradition as a way of thinking. It is easy to spot a tradition of ”Saami attitude”, one that brings forth a pragmatic, composite and complex vernacular architecture often bearing the quintessential elements of recycling and spontaneous use of materials such as local wood, plastic and fiber cloths, folded-out oil barrels, cardboard, isolation-foam, etc and whatever else might be available on site.”

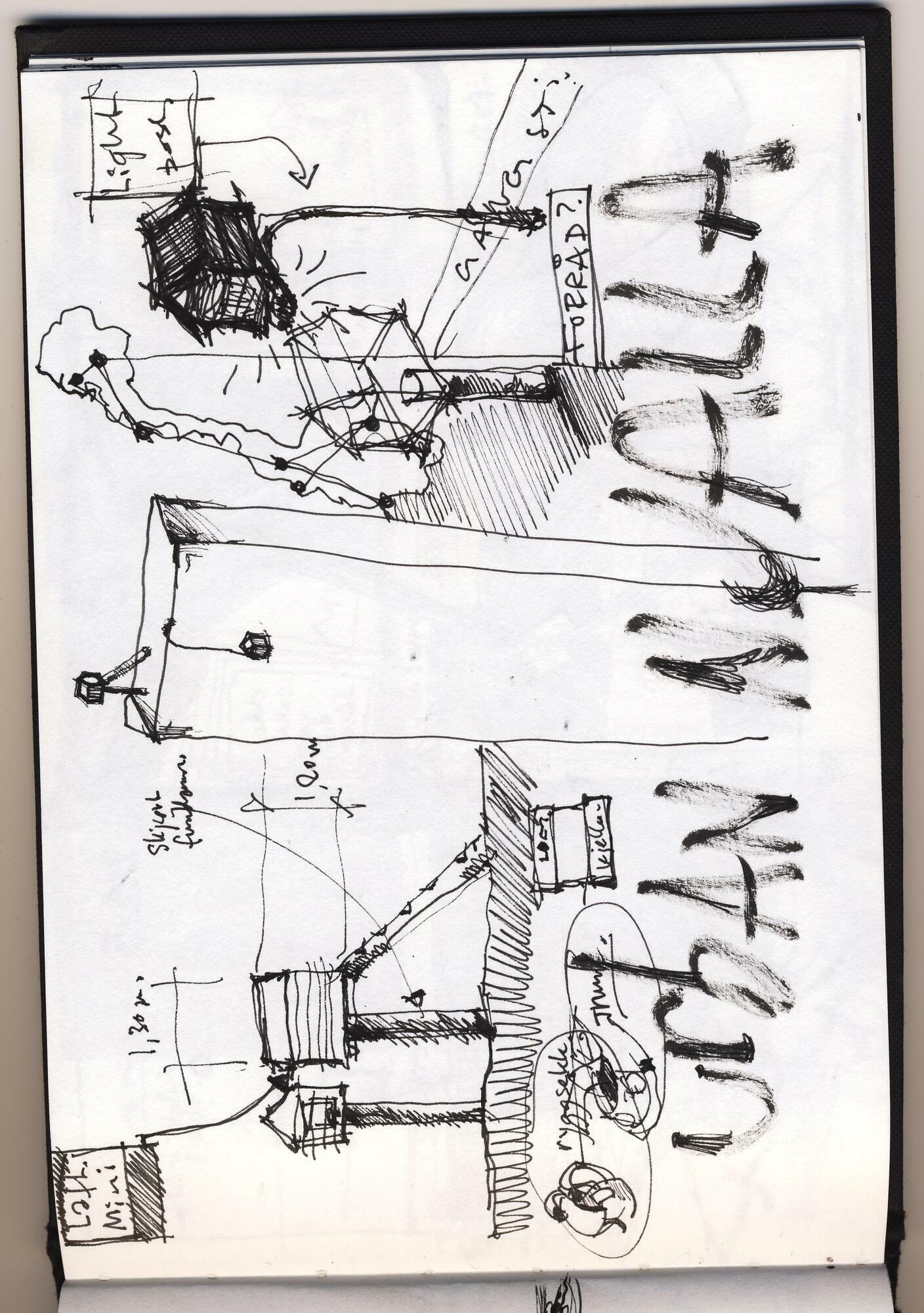

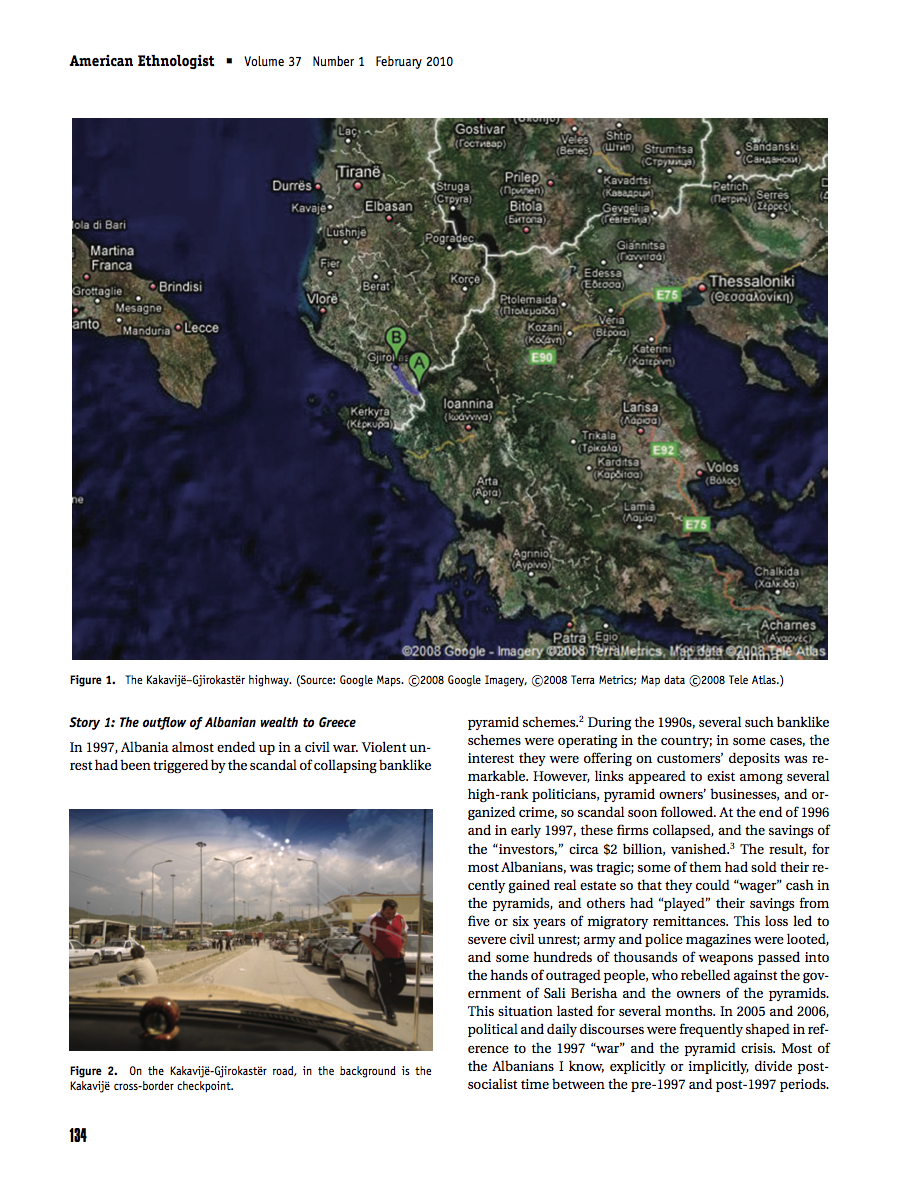

Joar Nango: The Saami Building Tradition: A Complex Picture,

”Instead of letting an ethnical viewpoint simplify the picture and define the Saami building tradition as a whole, it’s more useful to focus on the Saami way of thinking, where the unified Saami building traditions is recognized by a sensitive relation to the landscape and the specific ecological, spiritual and historical criteria provided by the site itself.”

Joar Nango: The Saami Building Tradition: A Complex Picture,

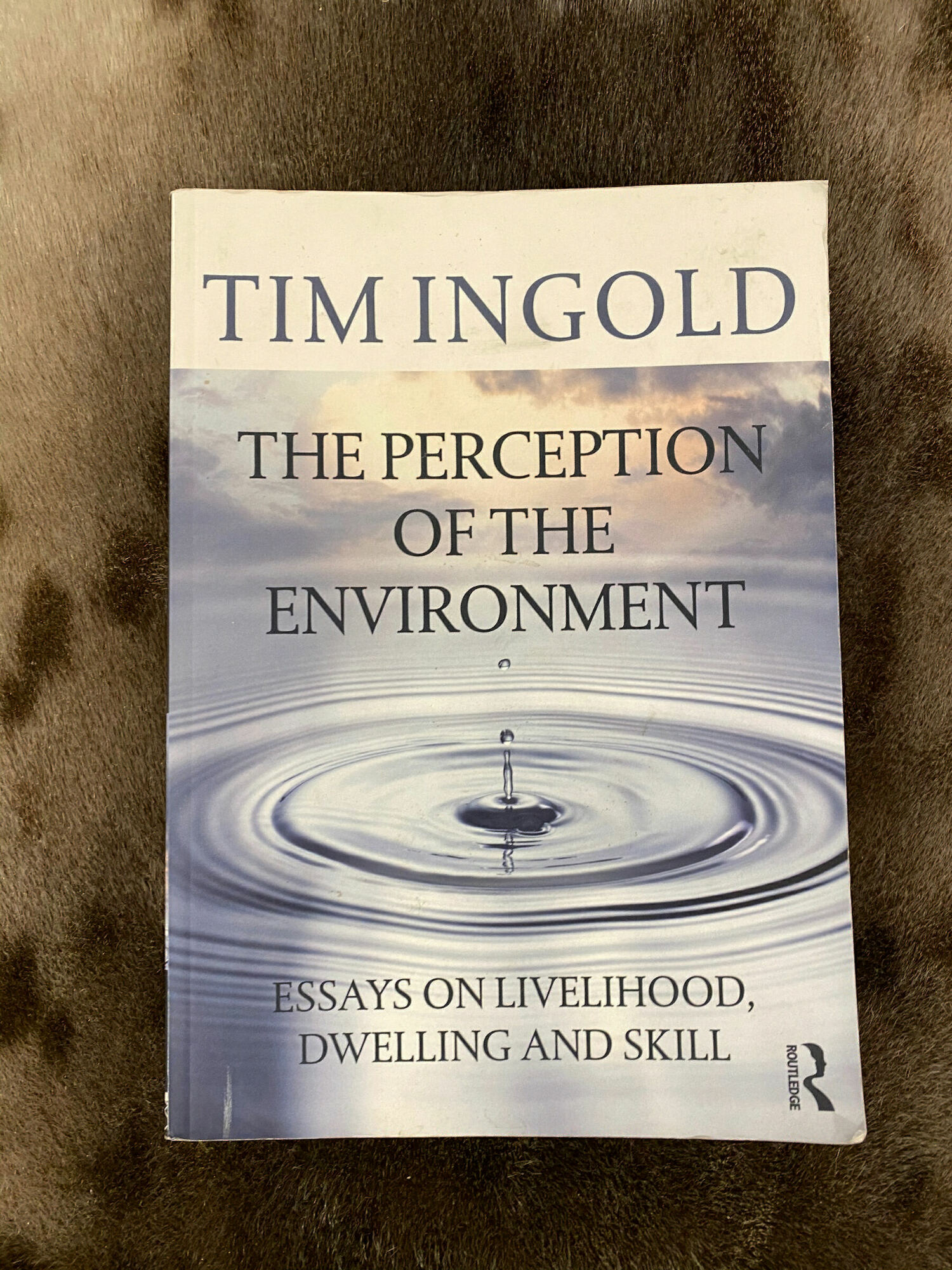

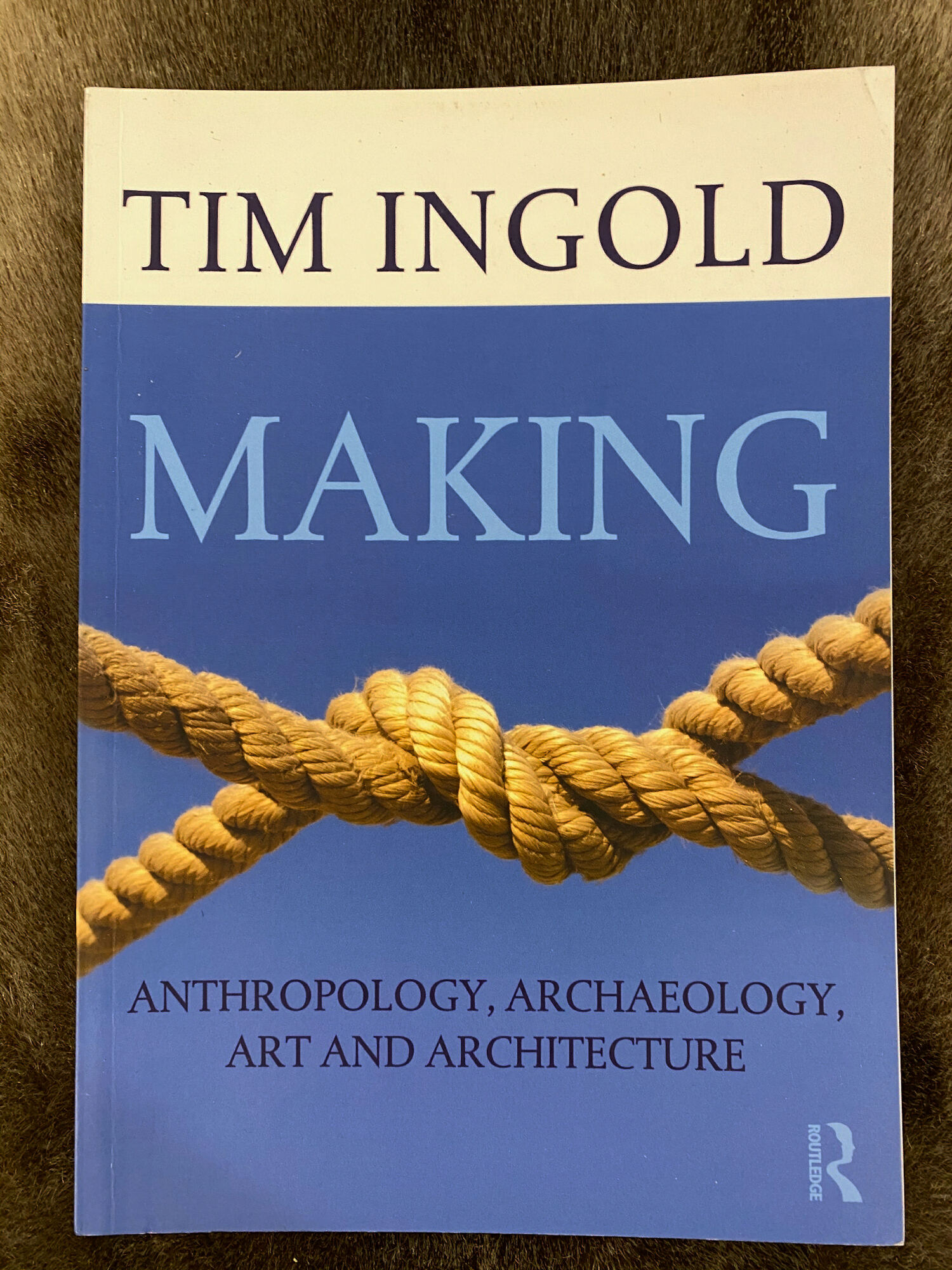

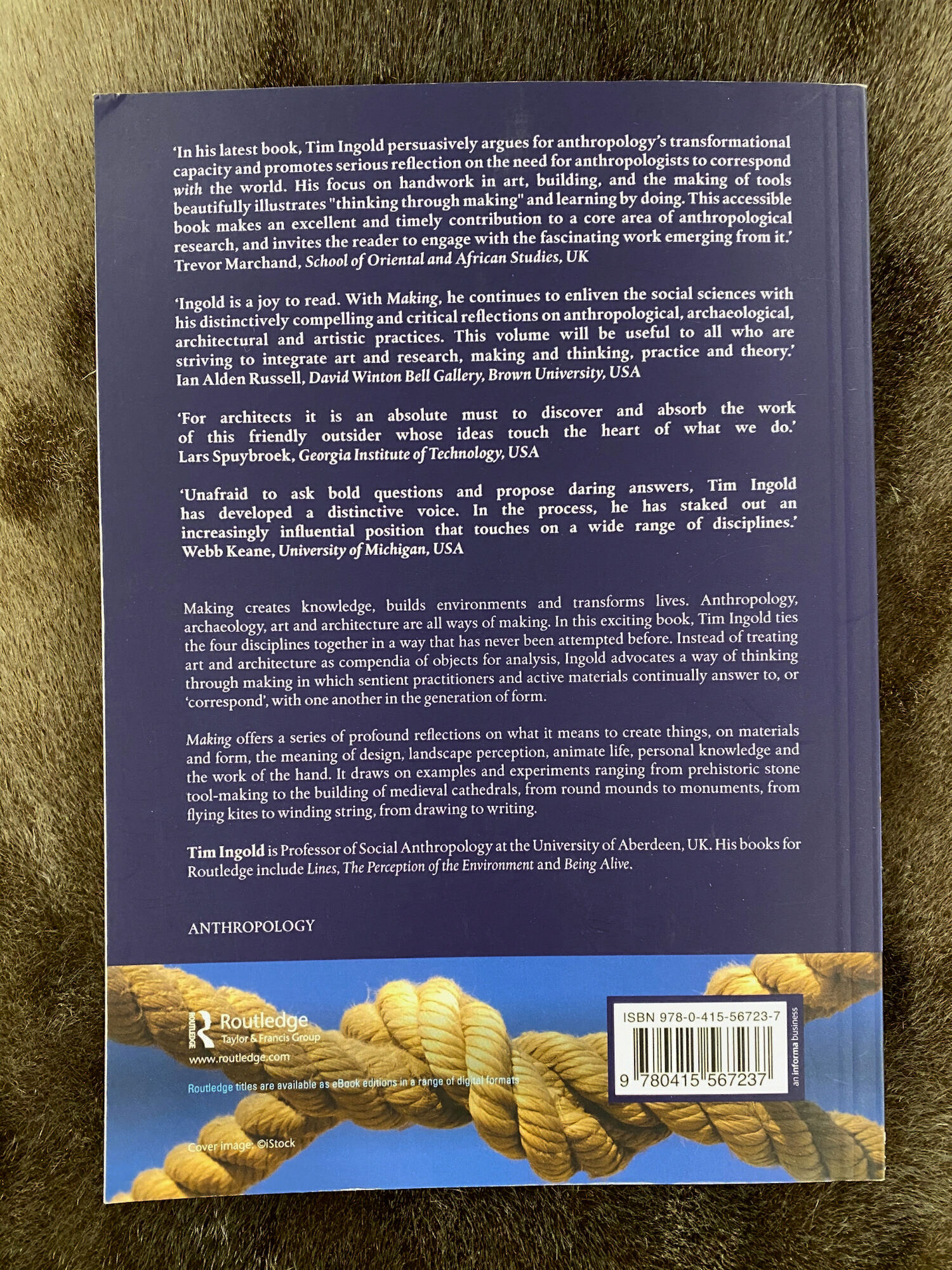

For Tim Ingold, imagining the future, dissolves the boundaries between the future and past. In his writings, the imagination is intimately entangled with perception and memory such that they cannot be considered independently. Against the idea that limited futures are coming directly at us, Ingold locates the imagination as an activity, technique and subject in scenes of everyday life and as the means by which worlds come to be.

TIM INGOLD

Tim Ingold: THE YOUNG, THE OLD AND THE GENERATION OF NOW,

Tim Ingold is Emeritus Professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Aberdeen. He is a Fellow of the British Academy and of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. He is the author of Anthropology: Why It Matters (2018), The Life of Lines (2015), Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description (2011), Lines: A Brief History (2007), Tools, Language and Cognition in Human Evolution (with Kathleen Gibson, 1993) and The Appropriation of Nature (1986), among numerous other books and publications.

“We are inclined nowadays to judge a work as art not by the accuracy of its depiction but by the novelty of its conception. Yet no practice of art could carry force that was not already grounded in careful and attentive observation of the lived world. Nor, conversely, could anthropological studies of the manifold ways along which life is lived be of any avail if not brought to bear upon speculative inquiries into what the possibilities of life might be. Thus, far from the one looking only forward and the other only back, contemporary art and anthropology have in common that they both observe and speculate. Their orientations are as much towards human futures as towards human pasts; these are futures, however, that are not conjured from thin air but forged in the crucible of collective lives. I contend that for both art and anthropology, the aim is – or at least should be – to join with these lives in the common task of fashioning a world fit for coming generations to inhabit.”

Vents Vīnbergs: Research as, a Labour of love, 04.08.2020

“The traces of Block P are frames of concrete, a grid that sits deep in the ground, cut down until the ground slides over it. Here Nuuk breathes in. An empty space in the city centre, a space of opportunities, time that slips and slides, time that flies, floats, time gone by and time that came.”

Tone Huse: Blok P, objektstudie., 31.8.2016

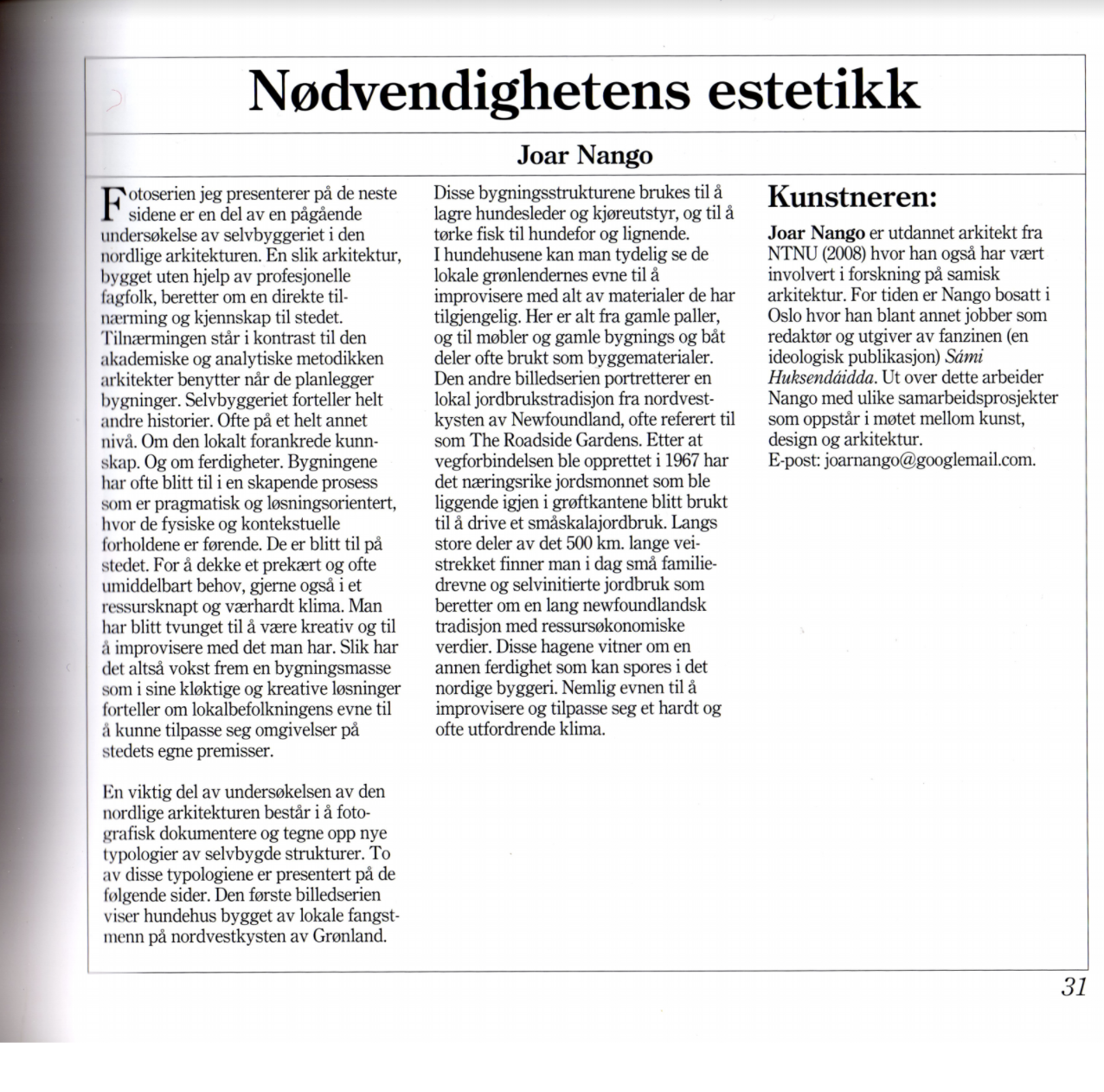

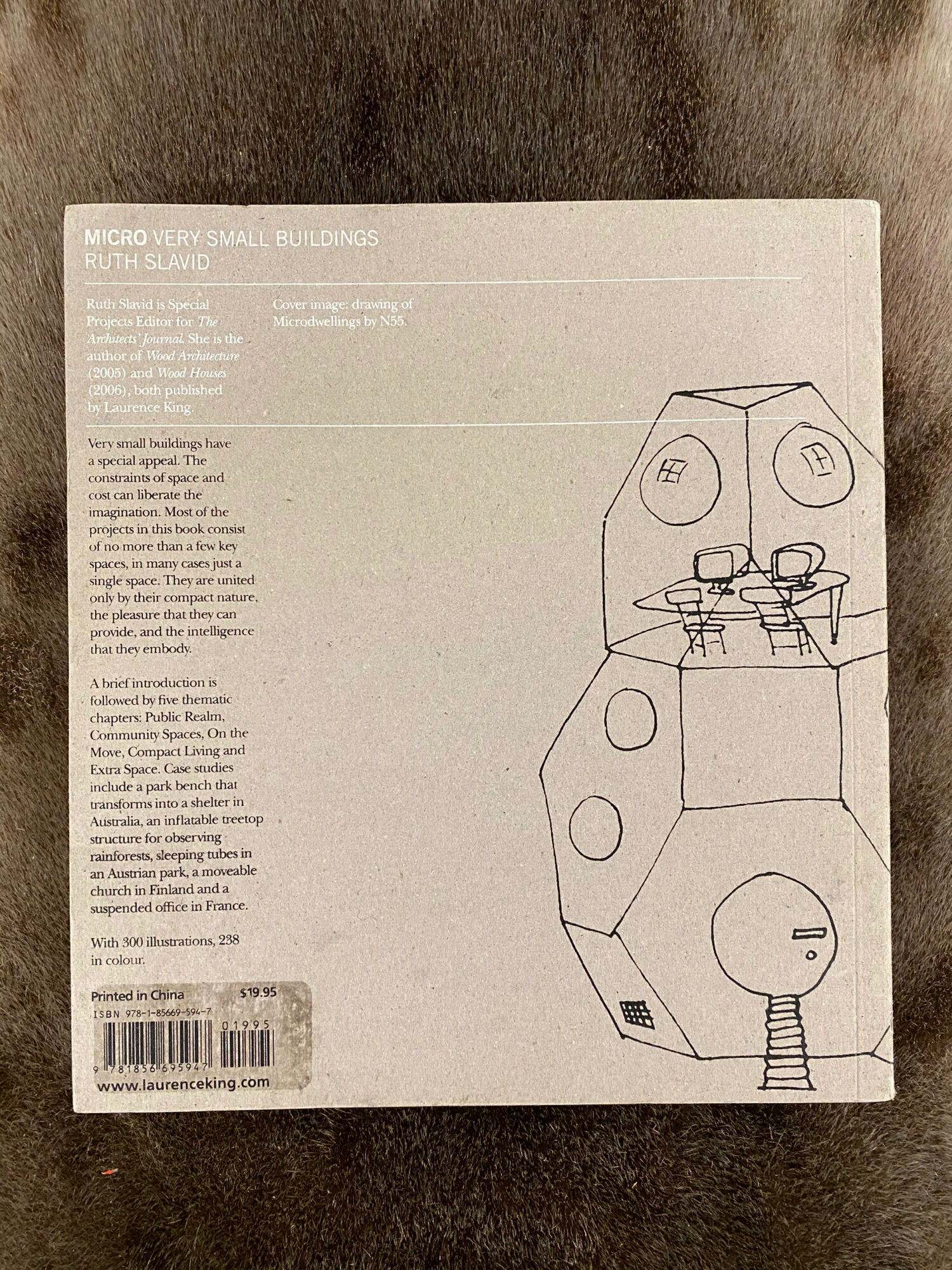

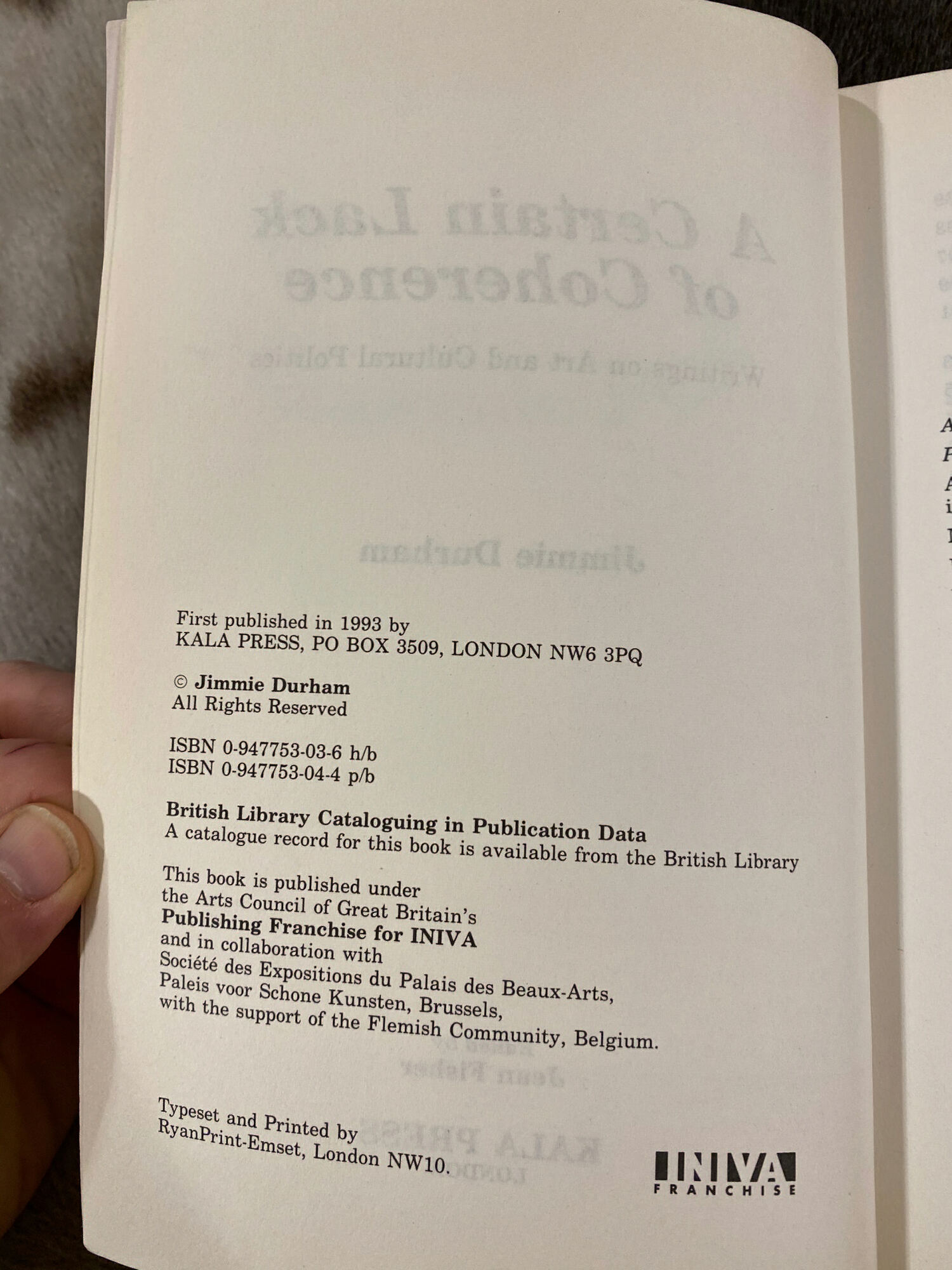

Joar Nango: Nødvendighetens Estetikk, 2010